For decades, a single strip of ancient linen has stood at the center of one of the most enduring scientific controversies in modern history.

Few objects on Earth have been examined as intensely, debated as fiercely, or questioned as relentlessly as the Shroud of Turin.

Declared medieval by a landmark scientific test in 1988, the relic should have faded into historical certainty.

Instead, each new layer of investigation has complicated the picture, leaving researchers facing a paradox where more data produces less clarity.

The controversy began with confidence.

In April 1988, church authorities authorized a radiocarbon dating test intended to settle the question of age once and for all.

A narrow strip of cloth, measuring only 81 millimeters by 16 millimeters, was removed from the lower edge of the linen.

Under close supervision by representatives from the Vatican, textile experts, and the British Museum, the sample was divided into three portions.

These were distributed to world class laboratories in Oxford, Zurich, and Arizona.

Each facility used accelerator mass spectrometry, the most advanced method available at the time.

The result appeared decisive.

All three laboratories independently dated their samples to a range between 1260 and 1390 AD.

The British Museum announced that the findings were statistically consistent and confirmed a medieval origin.

Media outlets around the world declared the mystery solved.

For many observers, the debate ended that year.

Yet beneath the surface, doubts were already forming.

The sample had been taken from a single corner of the cloth, an area known to have been handled repeatedly and possibly repaired after a fire in 1532.

No fibers from the central or image bearing regions were tested.

Critics soon argued that the chosen location might not represent the age of the entire linen.

Years later, when the raw radiocarbon data became publicly available, statisticians noticed irregularities.

The average dates reported by the three laboratories differed more than expected.

When chi squared tests were applied, the variation exceeded acceptable limits.

The resulting p values fell below 0.

05, indicating that the data sets were not fully compatible.

This statistical heterogeneity suggested that the samples might not all originate from material of the same age.

The focus then shifted from physics to chemistry.

Ray Rogers, a chemist affiliated with the original Shroud of Turin Research Project, pursued an alternative line of inquiry.

Rather than dating the cloth through radioactive decay, he examined the molecular condition of the linen fibers themselves.

Rogers concentrated on vanillin, a compound produced during the breakdown of lignin in flax fibers.

Over time, vanillin gradually disappears, providing a chemical clock that cannot be easily reset.

Rogers compared fibers from the radiocarbon sample area with fibers taken from the main body of the linen, along with control samples from medieval European cloth and ancient Egyptian textiles.

His findings were striking.

Threads from the tested corner still contained detectable vanillin, while fibers from the main cloth showed none.

According to Rogers, this absence suggested an age well beyond the medieval period, possibly exceeding thirteen centuries.

Microscopic analysis further revealed traces of cotton interwoven with the linen in the sampled corner, along with dye residues consistent with later repair work.

Rogers concluded that the radiocarbon sample came from a rewoven patch, combining older linen with newer threads.

His results, published in 2005, did not directly invalidate the 1988 test but raised serious questions about whether it had dated the original cloth at all.

While debates over age continued, attention turned to the image itself.

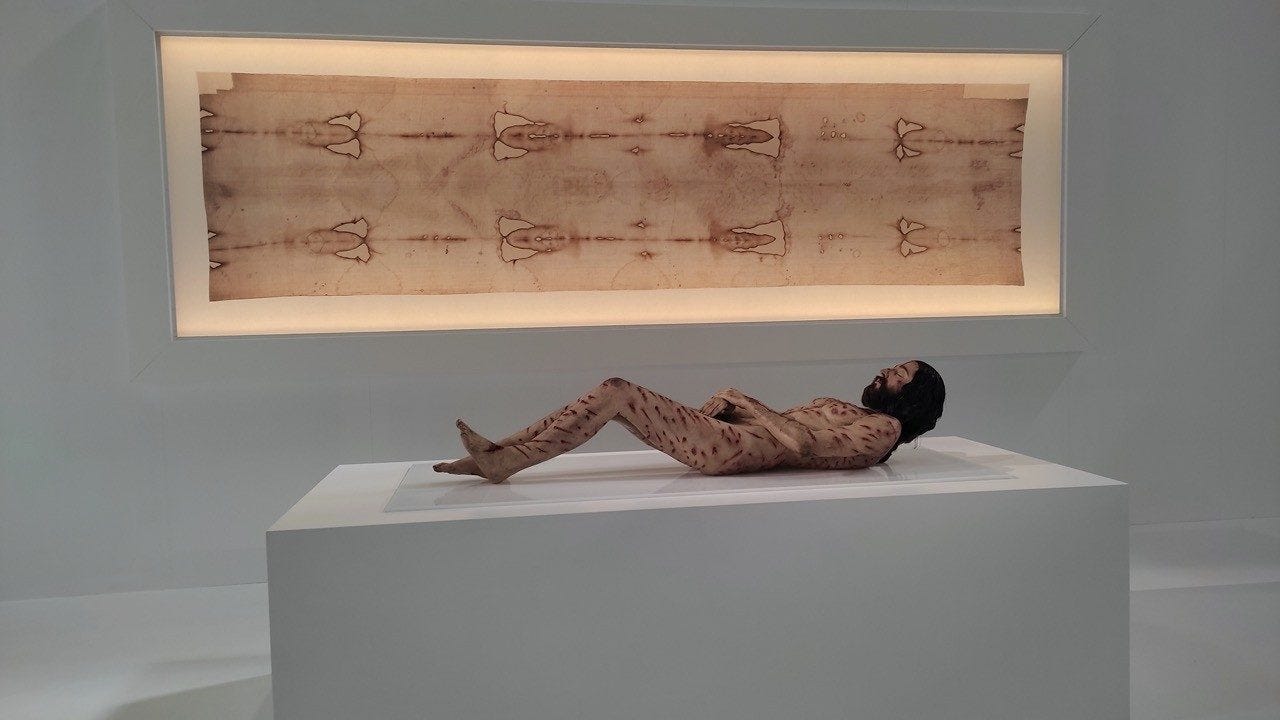

Under magnification, the figure on the linen behaves unlike any known work of art.

There are no brush strokes, no pigment particles, and no evidence of binding agents such as egg or glue.

The coloration exists only on the outermost fibrils of the threads, penetrating no deeper than 200 nanometers.

This superficial discoloration is thinner than a thousandth of a human hair.

Researchers from the 1978 Shroud of Turin Research Project conducted extensive chemical, optical, and spectroscopic tests.

They found that the image areas do not fluoresce like paint or organic stains under ultraviolet light.

The fibers remain chemically identical to the surrounding cloth except for a subtle dehydration and oxidation consistent with mild thermal alteration.

Attempts to reproduce the image using known techniques have consistently failed.

Pigments soak too deeply.

Heat scorches leave damage far more extensive than observed.

Mechanical rubbing produces uneven results.

In every experiment, telltale signs of human fabrication remain visible.

The shroud image, by contrast, disappears under close inspection and emerges only at a distance.

Another anomaly lies in the image encoding of three dimensional information.

When image intensity is mapped to vertical relief, the resulting data forms a coherent three dimensional representation of a human body.

This property does not appear in paintings or photographs and would have been unknown to medieval artisans.

Equally perplexing are the blood stains.

Forensic analyses confirm the presence of real human blood, identified as type AB.

Hemoglobin and serum proteins have been detected deep within the fibers, consistent with natural absorption rather than surface application.

Under ultraviolet light, the stains display characteristics of genuine hematic material, not mineral pigment.

The sequence of formation is critical.

Blood marks appear to have been deposited before the body image formed.

In all cases, the image stops abruptly at the edge of each stain, as though the process that created the image did not act on blood covered areas.

This order defies conventional artistic logic and would require extraordinary foresight to fabricate.

Within the scientific team, disagreements were intense.

Chemist Walter McCrone argued that the image resulted from iron oxide pigment.

However, repeated tests failed to detect sufficient quantities of such materials, and no binding medium was ever identified.

As evidence accumulated, the pigment hypothesis lost support among independent researchers.

In recent years, new non destructive methods have entered the debate.

In 2022, a team led by Liberato De Caro at the Institute of Crystallography in Italy applied wide angle X ray scattering to flax fibers from the cloth.

This technique measures changes in cellulose crystallinity that occur over long periods.

The shroud sample was compared to dated linens, including cloth from Masada in Israel.

The molecular signature of the shroud closely matched first century textiles rather than medieval examples.

According to the researchers, achieving such degradation in only seven centuries would require exposure to extreme heat and humidity inconsistent with the cloth known history.

Independent replication by a group in Naples produced similar results, adding weight to the findings.

Botanical evidence adds another layer.

In the 1970s, Swiss botanist Max Frei collected pollen samples from the linen using adhesive tape.

He identified dozens of plant species, many native to the Levant and Anatolia, including varieties not found in Europe.

While critics questioned his methodology, the geographic diversity of the pollen remains difficult to dismiss.

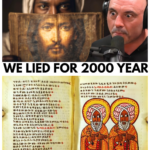

Digital technology has also reshaped public engagement.

High resolution photography and computed tomography have been used to construct detailed three dimensional models of the figure.

Exhibited in the Vatican, these reconstructions reveal anatomical features consistent with historical descriptions of Roman era punishment practices.

The relic survival has also shaped its modern history.

During a fire in 1997 at the chapel in Turin, a firefighter broke through armored glass and carried the protective case to safety moments before structural collapse.

The linen emerged unharmed, reinforcing its symbolic resilience.

Since that incident, access has been tightly restricted.

Church authorities permit only non invasive testing.

Proposals for new radiocarbon sampling from untouched areas remain unanswered.

For now, imaging and spectroscopy are the only approved tools.

As it stands, the shroud occupies a unique position.

Some evidence supports a medieval origin.

Other data suggests far greater antiquity.

No single explanation accounts for all observations.

The object resists categorization, challenging both scientific methodology and historical assumptions.

In an age of artificial intelligence and advanced analytics, the linen remains stubbornly enigmatic.

Each technological leap has illuminated details but failed to deliver closure.

The mystery endures not from lack of study, but from an excess of conflicting facts.

The shroud continues to exist at the boundary between what can be measured and what remains unknown, inviting future generations to confront the limits of certainty itself.

News

Ethiopian Bible Describes Jesus in Incredible Detail And It’s Not What You Think

The Ethiopian Bible is one of the most mysterious and least understood sacred texts on earth. Written in gears, an…

Joe Rogan Asks Bible Expert TOUGH Questions About Jesus: EPIC Responses

A recent in depth conversation between globally recognized podcast host Joe Rogan and Christian Bible scholar and historian Wes Huff…

BREAKING: California Lake Oroville Rose 23 Feet Overnight And Scientists Don’t Understand Why

California water officials are facing an unprecedented and deeply unsettling situation at Lake Oroville, the most critical reservoir in the…

THOUSANDS of MS 13 Gang Members Arrested in Largest Multi City FBI & ICE Crackdown

In early 2024, United States federal authorities carried out the largest coordinated gang enforcement action in modern national history. The…

Unreleased Jim Caviezel Interview That Will Leave You Speechless

The appearance of actor Jim Caviezel at a public faith centered gathering in Atlanta became more than a routine interview….

China Just Shocked the World With What They’re Building!

In recent years, global attention has often focused on short term headlines, political disputes, and market volatility. Meanwhile, a profound…

End of content

No more pages to load