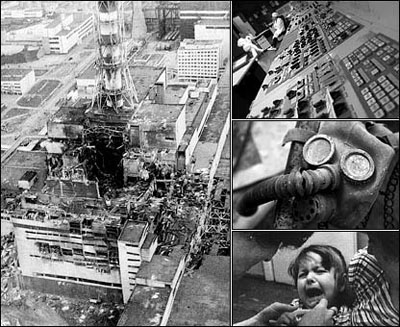

It is now widely accepted that the Soviet Union suffered one of the most severe nuclear disasters in human history when reactor number four at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant exploded in April 1986.

Massive amounts of radioactive material were released into the atmosphere, contaminating large areas of what is now Ukraine, Belarus, and parts of Europe.

For decades, Chernobyl was described as a dead zone, a poisoned landscape where life had been permanently erased.

The surrounding exclusion zone became a symbol of destruction, fear, and irreversible damage caused by nuclear technology.

In the years following the disaster, scientists believed that radiation levels would make survival impossible for most forms of life.

Forests near the reactor withered and turned red, birds vanished from the skies, and entire towns were abandoned almost overnight.

The region appeared frozen in time, left as a silent warning to the world.

Yet decades later, careful scientific observation has revealed a far more complex and unexpected reality.

Against all expectations, wildlife has returned to Chernobyl in surprising numbers, challenging long-held assumptions about nature, radiation, and survival.

To understand this transformation, it is necessary to return to the night of the explosion.

In the early hours of April twenty sixth nineteen eighty six, a safety test was underway at reactor number four.

A series of technical failures combined with human error caused the reactor to become unstable.

Heat and pressure increased rapidly inside the core.

Moments later, a powerful explosion tore through the building, exposing the reactor to the open air.

A bright glow illuminated the night sky as radioactive material was propelled high into the atmosphere.

At the nearby city of Pripyat, residents noticed an unusual light and smoke rising from the plant.

No official warning was issued.

Many people assumed there had been a routine industrial accident and returned to their homes.

Children went to school the next morning as usual.

By then, radioactive particles were already spreading silently across the city.

Firefighters rushed to the scene without protective equipment, unaware that burning graphite fragments scattered across the roof were intensely radioactive.

Many of these first responders later died from acute radiation sickness.

Within days, authorities ordered the evacuation of Pripyat and surrounding villages.

Residents were told the evacuation would be temporary and that they would return soon.

Homes were left intact, with food on tables, toys in bedrooms, and personal belongings untouched.

That return never happened.

The exclusion zone was established, sealing off more than two thousand square kilometers of land.

Human activity largely disappeared from the region, leaving behind empty streets, decaying buildings, and overgrown farmland.

One of the most dangerous threats following the explosion lay beneath the reactor itself.

Molten nuclear fuel was melting downward through damaged concrete toward a large pool of water.

If the molten material had reached the water, it could have triggered a massive steam explosion, spreading even more radiation across Europe.

To prevent this, a small group of plant workers entered a flooded chamber beneath the reactor to manually open drainage valves.

Their mission succeeded, draining the water and reducing the risk of further catastrophe.

Their actions bought critical time and helped stabilize the site.

In the months that followed, hundreds of thousands of workers known as liquidators were mobilized to contain the disaster.

Soldiers, engineers, miners, and civilians worked in hazardous conditions to remove debris, bury contaminated materials, and construct a concrete structure around the damaged reactor.

Exposure limits were strictly enforced, with workers rotating in short shifts to reduce radiation doses.

Their collective effort significantly reduced the spread of contamination and prevented even greater harm to surrounding regions.

When the major cleanup operations ended, the exclusion zone became quiet once more.

Human presence declined to a minimum, limited to scientists, security personnel, and maintenance crews.

Farms, factories, and roads fell into disuse.

Forests reclaimed abandoned villages, and wildlife corridors replaced streets.

It was in this silence that nature began an unexpected recovery.

Years later, scientists sought to understand how animals were using the exclusion zone.

Direct observation was difficult due to safety concerns and the size of the area.

To overcome this, researchers installed motion activated cameras throughout the region.

These cameras were placed in both heavily contaminated areas and zones with lower radiation levels.

Their purpose was to document which species were present and how they moved through the landscape.

At first, the footage showed little activity.

Slowly, animals began to appear.

Deer crossed open fields.

Foxes explored abandoned buildings.

Wild boar rooted through forest soil.

Over time, the cameras captured wolves, elk, lynx, birds, and many smaller species.

Some of these animals had been rare or absent in the region before the disaster.

Others appeared in higher numbers than expected.

The findings revealed that wildlife was not merely passing through the exclusion zone but establishing stable populations.

With no hunting, agriculture, or urban development, animals found abundant space and resources.

Forests expanded, wetlands recovered, and prey species flourished.

Predators followed.

The absence of humans appeared to outweigh the risks posed by lingering radiation for many species.

Wolves became one of the most closely studied animals in the zone.

Camera footage showed packs raising young and occupying large territories year after year.

Researchers compared these wolves with populations living outside the exclusion zone and found that wolf numbers were significantly higher within the restricted area.

The availability of prey and lack of human disturbance allowed the species to thrive despite environmental contamination.

Scientists extended their research beyond behavior to examine biological changes.

Blood and tissue samples from wolves and other animals were collected and compared with samples from non contaminated regions.

Genetic analysis revealed differences linked to immune system function.

These changes suggested that some animals were adapting biologically to long term environmental stress.

This did not indicate immunity to radiation, but rather adjustments that may help mitigate damage.

Similar genetic variations were observed in certain bird species and small mammals.

The effects were not uniform across all species or individuals.

Some changes appeared neutral, others potentially beneficial, and some possibly harmful in the long term.

These findings highlighted the complexity of adaptation in challenging environments and demonstrated that recovery does not follow a single path.

Despite these signs of ecological resilience, scientists emphasize that the exclusion zone is not safe for unrestricted human habitation.

Radiation levels vary widely across the region.

Certain hotspots near the reactor and the red forest still contain dangerous concentrations of radioactive material.

Rain, wind, and soil movement continue to redistribute contamination, creating areas of elevated risk.

Ongoing monitoring remains essential.

Researchers use sensors, mapping tools, and field surveys to track radiation levels and ecological changes.

Entry into some areas is strictly controlled, and protective measures are required for those working on site.

Radioactive elements with long half lives will remain in the environment for decades or longer, ensuring that Chernobyl will continue to demand careful oversight.

The Chernobyl exclusion zone stands as a place of contrast.

It is both a damaged landscape shaped by human error and a functioning ecosystem shaped by the absence of human activity.

Forests grow among abandoned buildings.

Rivers flow through empty towns.

Animals move freely across land once filled with people.

Damage and renewal exist side by side, offering valuable lessons about environmental recovery and responsibility.

The return of wildlife does not erase the tragedy of Chernobyl or diminish its human cost.

Entire communities were displaced, lives were lost, and the consequences of the disaster continue to affect health, politics, and energy policy worldwide.

Yet the unexpected resurgence of life within the exclusion zone challenges simplistic views of destruction and recovery.

Chernobyl remains a warning about the long lasting impact of technological failure and the limits of human control.

At the same time, it reveals the resilience of natural systems when given space and time.

Decades after the explosion, the region continues to evolve, reminding the world that nature adapts in complex ways, even in the shadow of catastrophe.

News

The Hidden Chamber of Machu Picchu: A Discovery That Changes Everything

The Hidden Chamber of Machu Picchu: A Discovery That Changes Everything Deep in the heart of Peru, where the Andes…

The Titanic’s Secrets: What Robert Ballard Discovered at the Wreck

The Titanic’s Secrets: What Robert Ballard Discovered at the Wreck In a stunning revelation that has captivated historians and enthusiasts…

The Hidden Truth: Are There Lost Civilizations Beneath Antarctica?

The Hidden Truth: Are There Lost Civilizations Beneath Antarctica? In the icy expanse of Antarctica, where the wind howls like…

“The Unbelievable Discovery: Is MH370 Finally Found?”

“The Unbelievable Discovery: Is MH370 Finally Found?” On the fateful night of March 8, 2014, a Malaysia Airlines flight carrying…

“The Lake of Legends: Alaska’s Real-Life Jaws Lurking Beneath the Surface—What Lies in Lake Iliamna?”

“The Lake of Legends: Alaska’s Real-Life Jaws Lurking Beneath the Surface—What Lies in Lake Iliamna?” To most, Lake Iliamna appears…

A Lost Assyrian Vault Was Discovered Under Nineveh — The Warnings On The Walls Are Terrifying

Sealed Assyrian Vault Beneath Nineveh Forces Archaeologists to Reconsider Ancient Warnings and Lost Knowledge Archaeologists working beneath the ruins of…

End of content

No more pages to load