For six seasons in the 1970s, Sanford and Son stood at the center of American television.

The sitcom, set in a Watts junkyard, delivered sharp punchlines, memorable catchphrases, and one of the most recognizable father and son dynamics in TV history.

Week after week, millions tuned in to watch the cranky but lovable Fred Sanford trade insults with his long suffering son Lamont.

The laughter felt effortless.

The chemistry felt natural.

Yet behind the bright studio lights and roaring audiences lived stories far more complicated than anything written into a half hour script.

At the heart of the show was Redd Foxx, born John Elroy Sanford, a performer whose life embodied contradiction.

Long before he became a household name, Foxx had built a reputation in smoke filled nightclubs as one of the boldest stand up comics in America.

His style belonged to the tradition known as blue comedy, a form built on raw language, adult themes, and fearless social commentary.

In small clubs and Las Vegas stages, he delivered routines that pushed boundaries and packed rooms.

His albums sold strongly, and among fellow comedians he was regarded as a legend.

That reputation made his transformation into Fred Sanford all the more remarkable.

On network television he portrayed a junk dealer with exaggerated stubbornness and theatrical chest clutching gags.

The character was mischievous but family friendly, mischievous yet accessible to prime time audiences.

Viewers who adored Fred rarely realized that the man behind the role had once been considered too edgy for television standards.

Foxx effectively lived a double professional life.

In one world he was a headline act in casinos and late night clubs, thriving on uncensored humor.

In another he was the leading man of an NBC hit that had to satisfy sponsors and censors.

Balancing those worlds required more than versatility.

It demanded strategy.

As a Black entertainer in 1970s Hollywood, Foxx navigated an industry controlled largely by executives who did not share his background.

Fred Sanford had to be broadly appealing, yet Foxx resisted becoming a caricature.

Offstage he remained unapologetically himself, preserving the voice that had made him successful in the first place.

That tension between authenticity and expectation shaped his career and, at times, fueled open conflict.

Money became one of the most visible battlegrounds.

At the height of the show’s popularity, Foxx earned 35000 dollars per episode, an impressive salary for the era.

Still, he believed his compensation did not reflect the show’s cultural impact or his value as its central figure.

When he learned that Carroll O’Connor, star of All in the Family, commanded one of television’s highest paychecks, Foxx saw the comparison as symbolic.

For him, it was not simply about numbers.

It was about recognition and parity within an industry that often undervalued Black talent.

In 1974 he staged a dramatic walkout, publicly citing health concerns.

Production continued without him for several episodes, an unusual move for a sitcom built so heavily around one character.

NBC responded with legal pressure, and headlines chronicled the standoff.

Eventually a settlement was reached, and Foxx returned with a revised contract that reportedly included a percentage of the show’s profits.

The episode underscored how essential he was to the series.

Without Fred Sanford, the junkyard felt empty.

Financial triumphs, however, did not translate into long term stability.

Foxx enjoyed the rewards of success, spending freely on cars, homes, and entertainment.

Over time tax troubles mounted.

By the early 1980s he filed for bankruptcy, and later federal authorities seized assets over unpaid obligations.

The irony was painful.

The actor who had fought fiercely for higher pay found himself struggling with personal finances, mirroring in unexpected ways the fictional junk dealer who often joked about being broke.

Tragedy cast a shadow over his later years.

In October 1991, Foxx was rehearsing a new sitcom titled The Royal Family, developed with support from Eddie Murphy.

During rehearsal he collapsed after experiencing severe chest pain.

For years audiences had laughed at Fred Sanford’s exaggerated heart attack routine, complete with dramatic cries to a fictional Elizabeth.

When Foxx fell, some colleagues initially believed he was joking.

The situation quickly proved grave.

He suffered a fatal heart attack at age 68.

The heartbreaking similarity between his signature gag and his final moments left a lasting impression on Hollywood.

While Foxx commanded attention, the rest of the cast carried equally compelling histories.

Demond Wilson, who portrayed Lamont Sanford, brought depth shaped by experiences far removed from sitcom stages.

Before acting, he served in the United States Army during the Vietnam War and was wounded in combat.

The transition from battlefield to soundstage represented a dramatic shift.

Audiences saw a witty, patient son counterbalancing his father’s antics.

Few realized the composure on screen was grounded in real world hardship.

Wilson later revealed that the set was not always as carefree as viewers imagined.

He stated in interviews that during the 1970s he often carried a firearm for personal protection, reflecting broader anxieties in Los Angeles at the time.

Foxx reportedly did the same.

Fame increased visibility, and visibility sometimes brought fear.

The idea that two beloved sitcom stars felt compelled to remain armed while filming startled many fans when the information surfaced years later.

It illustrated how the social climate of the era extended beyond studio walls.

Tensions between Wilson and Foxx also emerged over the years.

When Foxx temporarily left the series amid contract disputes, Wilson learned of the development through media reports rather than direct conversation.

The perceived slight lingered.

In 2009 Wilson published a memoir titled Second Banana, reflecting on his years as what he felt was the supporting act to a larger than life star.

He expressed admiration for Foxx’s talent while acknowledging feelings of frustration and neglect.

Another breakout figure was LaWanda Page, who portrayed the sharp tongued Aunt Esther.

Before television fame, Page performed as a fire eater known as the Bronze Goddess of Fire, astonishing audiences with daring stage acts.

She later developed a stand up career filled with bold material that differed dramatically from her churchgoing sitcom persona.

When producers initially doubted her fit for the show, Foxx intervened, insisting she remain.

Their childhood friendship in St Louis strengthened that loyalty.

Aunt Esther became one of the series’ most memorable characters.

Whitman Mayo, who played the elderly Grady Wilson, was decades younger than his character.

Drawing inspiration from family members, he crafted the slow shuffle and distinctive speech that defined Grady.

His path to acting included military service and years working with youth before finding television success.

The layered backgrounds of the cast enriched performances that might otherwise have seemed purely comedic.

Don Bexley portrayed Bubba, a friend of Fred’s with easy charm.

A longtime companion of Foxx, Bexley had worked in music and comedy before making his television debut on the series in his sixties.

Their friendship endured until Foxx’s passing, when Bexley served as an honorary pallbearer.

Meanwhile Nathaniel Taylor, known as Rollo Lawson, faced legal trouble in the 1980s related to burglary charges.

He later redirected his energy toward mentoring young performers.

Lynn Hamilton, who played Donna Harris, brought theater experience and a stable personal life marked by a decades long marriage, offering quiet contrast to some of the turbulence around her.

Behind the scenes, creative battles shaped the show’s voice.

The writing staff was predominantly white, and scripts sometimes reflected limited familiarity with Black vernacular and culture.

Cast members pushed back, revising dialogue to sound authentic.

In certain episodes, Foxx insisted on confronting uncomfortable language or themes directly, arguing that honesty mattered more than executive comfort.

Studio audiences often responded enthusiastically, even when network officials worried about sponsor reaction.

These disputes highlighted broader questions about representation and creative control in American television.

When Sanford and Son premiered in 1972, it helped expand opportunities for Black performers in prime time.

Its humor masked serious undercurrents: debates over fairness, identity, and economic power.

The junkyard set symbolized working class resilience, yet off camera the actors grappled with issues ranging from financial strain to personal safety.

The laughter heard in living rooms across the nation coexisted with pressures invisible to viewers.

Foxx’s life encapsulated those contradictions.

He was fiercely loyal to friends like Page and Bexley, yet capable of abrupt departures during disputes.

He commanded one of the era’s highest salaries, yet struggled with money management.

He created a comedic heart attack routine that became iconic, yet succumbed to an actual cardiac emergency in front of colleagues.

His career bridged nightclub stages and mainstream television, raw club monologues and carefully timed network punchlines.

Decades later, the legacy of the series endures.

Reruns continue to attract new generations, and Fred Sanford’s exaggerated expressions remain embedded in popular culture.

What audiences often remember is the humor.

What history increasingly recognizes is the complexity behind it.

The cast members were not merely characters trading jokes in a fictional junkyard.

They were individuals shaped by war service, financial battles, artistic disagreements, and shifting social realities.

In examining the full story, the sitcom emerges as more than entertainment.

It becomes a lens into an era when Black performers fought for authenticity within restrictive systems.

It reflects how fame can amplify both opportunity and vulnerability.

And it reminds viewers that even the most lighthearted comedy can carry unseen weight.

The junkyard laughs were real, but so were the struggles that unfolded once the cameras stopped rolling.

News

Apollo 11 Astronaut Reveals Spooky Secret About Mission To Far Side Of The Moon! 10t

The Apollo 11 mission remains one of humanity’s greatest achievements, a defining moment when human beings first set foot on…

Bruce Lee’s Daughter in 2026: The Last Guardian of a Legend 10t

As a child, Shannon Lee would sometimes respond to playground bravado with quiet certainty. When other children joked that their…

Selena Quintanilla Died 30 Years Ago, Now Her Husband Breaks The Silence Leaving The World Shocked 10t

Thirty years have passed since the world lost one of Latin music’s brightest stars, yet the name Selena Quintanilla continues…

Scientists New Plan To Retrieve the Titanic Changes Everything! 10t

More than a century after the RMS Titanic slipped beneath the icy waters of the North Atlantic, the legendary ocean…

Drunk Dancer Challenged Michael Jackson — His Response Stunned 80,000 Fans

July 16th, 1989, Wembley Stadium. 80,000 people watched as a drunk backup dancer stumbled onto the stage during Billy Jean…

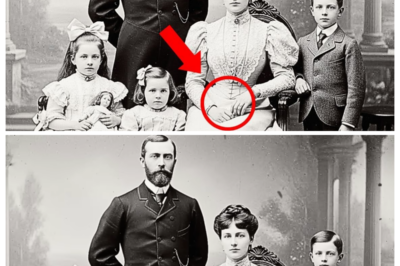

1890 Family Portrait Discovered — And Historians Recoil When They Enlarge the Mother’s Hand

This 1890 family portrait is discovered, and historians are startled when they enlarge the image of the mother’s hand. The…

End of content

No more pages to load