For more than six decades, Ron Howard has occupied a rare position in Hollywood.

He is widely perceived as one of the industry’s most agreeable figures—a former child star who transitioned seamlessly into a respected director, known for calm leadership, professionalism, and an almost unfailing sense of goodwill.

Yet longevity at the highest levels of filmmaking is never sustained by kindness alone.

Beneath Howard’s approachable demeanor lies a career shaped by difficult personalities, clashing egos, and formative encounters that revealed the sharper edges of the entertainment industry.

Long before he became an Oscar-winning director, Howard learned that survival in Hollywood often requires patience, resilience, and the ability to navigate conflict without losing one’s sense of self.

Howard’s earliest lessons came during his childhood on The Andy Griffith Show, where the comforting image of Mayberry masked more complex realities behind the scenes.

Frances Bavier, who portrayed the nurturing Aunt Bee, was beloved by audiences for her warmth and maternal presence.

Off camera, however, she maintained a distant and often chilly relationship with the cast.

A classically trained stage actress, Bavier reportedly viewed the sitcom format as beneath her artistic aspirations.

She approached the set not as a communal workplace but as a professional obligation she felt trapped within.

For a young Howard, still learning how adults interacted in a working environment, the contrast between Bavier’s onscreen affection and her real-life detachment was deeply confusing.

Bavier’s demeanor was not marked by open hostility but by emotional withdrawal.

While other cast members embraced a relaxed and playful atmosphere, she remained rigid and aloof, uninterested in bonding or improvisation.

Howard later reflected that this was his first exposure to the idea that performance and personality are not the same.

The experience taught him an early and enduring lesson: onscreen chemistry is often manufactured through discipline rather than genuine connection.

Bavier’s dissatisfaction with her own career trajectory ultimately shaped her interactions, and her inability to reconcile personal ambition with public recognition became a quiet but powerful force on set.

For Howard, it was an introduction to the hidden resentments that sometimes accompany fame.

If Bavier embodied quiet resentment, Howard’s encounter with Yul Brynner introduced him to something far more imposing.

As a five-year-old actor on the film The Journey, Howard found himself working alongside a man whose presence dominated every space he entered.

Brynner, already an international icon, carried himself with the authority of someone accustomed to absolute control.

His intensity was not directed at Howard personally, but its effect was unmistakable.

The atmosphere around Brynner was one of intimidation rather than collaboration, and even experienced crew members deferred to him without question.

Brynner represented an era in which major stars were treated as untouchable figures, insulated by the studio system and granted extraordinary power.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2)/ron-howard-tout-031324-bcfcd9b2bdf14e7f82856163c23fdfc0.jpg)

His commanding demeanor created a set environment shaped by fear and obedience rather than shared creativity.

For Howard, who had grown up in a family-oriented working culture, the experience was unsettling.

It revealed how a single ego could influence an entire production and stifle the collective spirit of filmmaking.

Years later, Howard would consciously build sets defined by openness and respect, a direct reaction to the authoritarian model he witnessed as a child.

As Howard transitioned from acting to directing in the early 1980s, new challenges emerged—this time from performers who tested his authority rather than overwhelming him with status.

On Night Shift, his breakthrough feature as a director, Howard worked with Shelley Long, an actress known for her intelligence and meticulous approach.

Long’s commitment to understanding every nuance of her character often slowed production, as she questioned motivations, dialogue, and blocking long after others were ready to move forward.

Her method was rooted in artistic rigor rather than ego, but the effect was friction nonetheless.

Howard, still establishing himself as a leader, was forced to balance creative inquiry with the practical demands of a film set.

Long’s perfectionism required him to develop clarity and firmness, qualities that did not come naturally to someone known for cooperation rather than confrontation.

The experience taught Howard that being likable was not enough; a director also had to be decisive.

While Long’s performance ultimately benefited from her intensity, the process challenged Howard to define boundaries and maintain momentum.

It was a critical moment in his development, shaping the leadership style he would rely on throughout his career.

The stakes rose even higher when Howard later collaborated with Russell Crowe, an actor whose talent was matched by volatility.

On films such as A Beautiful Mind and Cinderella Man, Crowe brought extraordinary commitment to his roles, often questioning decisions and pushing for changes that aligned with his vision.

His intensity could energize a production or destabilize it, depending on how it was managed.

Howard found himself navigating a relationship built on constant negotiation, where creative disagreement was both inevitable and productive.

Crowe’s insistence on psychological authenticity—such as his desire to film scenes in chronological order—posed logistical challenges that most directors would resist outright.

Howard chose a different approach.

Rather than opposing Crowe’s demands reflexively, he evaluated their artistic merit and adapted when possible.

This flexibility strengthened their collaboration but required Howard to withstand prolonged pressure and emotional strain.

Working with Crowe taught him that conflict is not inherently destructive; when guided carefully, it can elevate a film.

However, it also reinforced the importance of maintaining authority in the face of overwhelming talent.

Not all challenges came from intensity or ambition.

Some arose from instability.

Actor Tom Sizemore, whose career was increasingly affected by substance abuse, represented a different kind of difficulty.

In industry circles Howard moved within, Sizemore became emblematic of the risks posed by personal struggles left unchecked.

Addiction introduced uncertainty into productions, creating anxiety not only about performance quality but about basic reliability.

For Howard, who valued structure and respect for the collective effort, this unpredictability was deeply troubling.

Sizemore’s situation highlighted the limits of empathy in a professional environment.

While Howard recognized the human pain underlying addiction, he also understood the responsibility a director holds to protect the crew and the project as a whole.

This experience reinforced the idea that kindness alone cannot resolve every problem.

Sometimes leadership requires making hard decisions, even when they involve personal loss or disappointment.

Sizemore’s decline became a cautionary lesson about accountability and the fragile balance between compassion and responsibility in Hollywood.

Perhaps the most emotionally complex challenge of Howard’s career unfolded not through hostility but through friendship.

On Happy Days, Howard was the central figure as Richie Cunningham, yet Henry Winkler’s portrayal of Fonzie quickly eclipsed all others.

Winkler’s rise was meteoric, and the industry’s response was swift.

Network executives shifted their focus, and Howard found himself gradually marginalized despite remaining the show’s narrative anchor.

The tension was not rooted in rivalry between the two actors, who maintained a close personal bond, but in the structural realities of television fame.

Howard experienced firsthand how quickly Hollywood can redirect its loyalty.

Though deeply hurt by the network’s treatment, he handled the situation with remarkable composure.

Rather than lashing out or allowing resentment to damage his relationships, he reassessed his future.

The experience ultimately propelled him toward directing, where creative control offered stability that acting no longer did.

Taken together, these encounters formed the foundation of Ron Howard’s enduring career.

From emotional distance to authoritarian dominance, from perfectionism to volatility, from addiction to professional displacement, he confronted nearly every archetype of difficulty Hollywood could offer.

Rather than becoming hardened or cynical, Howard absorbed these lessons and refined his approach.

He learned when to compromise and when to stand firm, when to listen and when to lead.

Today, Howard’s reputation as a steady and humane director is not the result of naivety, but of experience.

He has seen the industry at its most challenging and chosen to respond with integrity rather than bitterness.

His career stands as proof that resilience does not require cruelty, and that leadership can be built not by dominating others, but by understanding the forces that drive them.

In surviving Hollywood’s sharpest edges, Ron Howard did more than endure—he evolved.

News

Steven Greer Released New Huge Update on Buga Sphere — And It May Be Non-Human in Origin!

In a remote region of Colombia, construction workers stumbled upon an object that has since baffled scientists and researchers worldwide….

Ethical Hacker: “I’ll Show You Why Google Has Just Shut Down Their Quantum Chip”

The advent of digital computers transformed every facet of modern life, from communication and medicine to finance and transportation. Yet,…

Before His Death, Apollo 11’s ‘Third Astronaut’ Michael Collins FINALLY Admitted It

Michael Collins, often called the “forgotten astronaut” of Apollo 11, played a role in one of humanity’s most iconic achievements:…

Family Vanished in 2005 After Reporting a Home Intruder — 10 Years Later, Police Open the Chimney… What Could Have Been Hidden in a Chimney for a Decade? The family disappeared without a trace after reporting a mysterious intruder, leaving neighbors and authorities baffled for years. A decade later, police decided to investigate one last overlooked corner — the chimney — and what they found has left the community shaken and questioning everything.

Was it a clue, a grim discovery, or something even stranger? The chilling revelation changes the story of their disappearance forever — click the article link in the comments to see what was uncovered.

In October 2005, the Mitchell family disappeared without a trace from their home on Pine Valley Road. When police arrived…

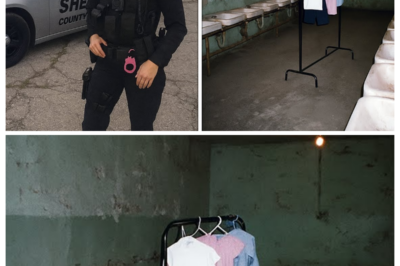

Deputy Investigated Abandoned Orphanage — What She Found in the Basement Changed Her Life Forever..

.

In November 2016, Deputy Ashley Turner responded to a call that seemed routine at first: reports of lights in an…

This 1920 Photo of a Girl Holding a Flower Looked Sweet — Until Restoration Revealed The Truth What Hidden Detail Did Modern Restoration Expose After a Century? At first glance, the 1920 photograph captures a charming scene: a young girl holding a delicate flower. But when experts digitally restored the image, they uncovered a shocking detail that changes everything we thought we saw.

Was it a hidden message, a forgotten story, or something far darker lurking in plain sight? The revelation has stunned historians and photography enthusiasts alike — click the article link in the comments to discover the truth.

In February 2024, a faded, water-damaged photograph appeared among unclaimed items at a Boston estate sale. The image showed a…

End of content

No more pages to load