A Vatican Revelation and the Doctrine That Shook the Church

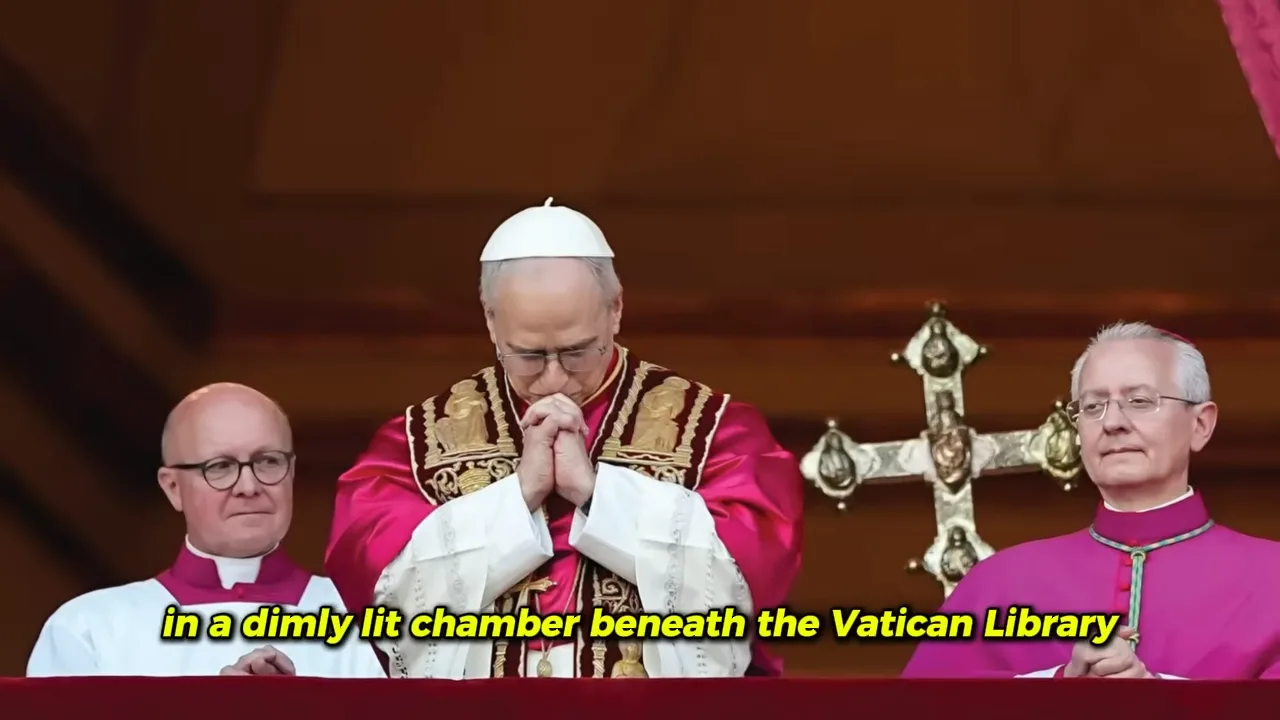

In the early hours before dawn, deep beneath the Vatican Library, Pope Leo XIV stood alone in a dimly lit chamber, holding an ancient manuscript whose fragile pages had remained hidden for more than fifteen centuries.

According to sources close to the pontiff, the Pope’s hands trembled slightly as he turned the final page.

The text, written in Coptic with Greek annotations, had been sealed since the fifth century.

“This changes everything,” he reportedly murmured to a trusted adviser.

Within hours, he would decide to reveal its contents to the world, setting in motion one of the most controversial moments in modern Church history.

Six months into his papacy, Pope Leo XIV had already established a reputation for unsettling long-standing Vatican conventions.

The American-born pontiff, formerly Cardinal Robert Francis Prevost, had spent decades serving remote parishes in the mountains of Peru before his unexpected election.

His pastoral background shaped a leadership style marked by openness, simplicity, and an unusual commitment to transparency.

While many welcomed these reforms, others within the Roman Curia watched his actions with growing unease.

That tension became evident on the morning before his weekly general audience.

Cardinal Vittoriano Santoro, a veteran prelate who had served three popes, stood in the shadows of the papal study as the Holy Father prepared his address.

Santoro, known for his cautious temperament, was troubled by reports of the Pope’s repeated late-night visits to the most restricted sections of the Vatican archives.

With visible hesitation, he conveyed the College of Cardinals’ request for clarification about rumors surrounding the following day’s speech.

The rumors concerned a set of manuscripts known informally as the Alexandrian Codex, sealed by Pope Celestine I in the fifth century.

These texts, according to archival records, had been deemed theologically dangerous during a time of intense doctrinal consolidation.

Pope Leo XIV listened calmly, then rose from his desk and approached a window overlooking St.Peter’s Square.

As dawn illuminated Rome, he spoke of courage, invoking not only Leo XIII, known for social teaching, but also Leo I, who had confronted Attila the Hun armed only with truth.

The Pope revealed that he had spent weeks translating the manuscripts himself.

What he found, he insisted, was not heresy but a forgotten articulation of a divine law that challenged Christian practice rather than doctrine.

The texts, attributed to the Apostle Thomas and corroborated by early Christian sources, described a principle of “divine reciprocity.

” According to this teaching, forgiveness granted by God corresponded precisely to forgiveness offered by human beings.

It was not a metaphor or moral suggestion, but a measurable spiritual law.

Santoro warned that such an idea could destabilize centuries of theological interpretation.

Yet Pope Leo XIV remained resolute.

He argued that the manuscripts illuminated Scripture rather than contradicting it, pointing to Christ’s words: “The measure you give will be the measure you get.

” In his view, the early Church had suppressed the texts not because they were false, but because they were considered too radical and threatening to established authority.

As concern spread among senior clergy, opposition quickly organized.

In a secure vault beneath the Apostolic Palace, several influential cardinals convened an emergency meeting.

Cardinal Domenico Veratti, a powerful figure within the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, warned that public disclosure of the Alexandrian Codex could undermine the Church’s moral authority.

He argued that the doctrine resembled forms of proto-Pelagianism by implying a calculable relationship between human action and divine judgment.

The group considered invoking an emergency protocol established in 1799, allowing the College of Cardinals to delay a papal pronouncement deemed harmful to the faith.

The measure required ninety-nine signatures within twenty-four hours.

Through rapid coordination and digital communication, Veratti’s coalition worked through the night to gather support.

By early morning, they believed they had succeeded.

Unbeknownst to them, Pope Leo XIV had anticipated resistance.

He quietly advanced the time of the general audience and ordered the complete digitization of the Alexandrian Codex.

Under his direction, Vatican technicians prepared to release the entire manuscript online, including translations in multiple languages, ensuring that the text could not be quietly reburied.

At 6:30 a.m., as the sun rose over St.Peter’s Square, an unusually large crowd gathered, joined by journalists sensing a historic announcement.

When the Pope appeared on the balcony, the square fell silent.

In a clear and deliberate address, he announced that a teaching on divine mercy had been hidden for fifteen centuries, not because it was false, but because it was feared.

He explained that these authenticated fifth-century texts described forgiveness as operating according to a precise spiritual law: each act of genuine forgiveness expanded a person’s capacity to receive divine mercy in equal measure.

As images of the ancient manuscript appeared on large screens, the Pope emphasized that this principle was grounded in Scripture itself.

“This is not poetry,” he declared.

“It is divine mechanics.

” Simultaneously, the Vatican website released the full codex to the public.

The reaction was immediate and intense.

Cheers, confusion, and disbelief rippled through the square as theologians and reporters struggled to grasp the implications.

Within hours, reactions poured in from around the world.

Some bishops praised the Pope’s courage and clarity.

Others expressed alarm, fearing a shift toward a works-based understanding of salvation.

Protestant leaders were similarly divided, with some acknowledging the scriptural resonance of the teaching and others rejecting its mathematical framing.

That afternoon, the College of Cardinals convened in emergency session.

Debate was fierce and unresolved.

While conservatives condemned the Pope’s unilateral action, others argued that he had fulfilled his role as supreme teacher of the Church.

By evening, no consensus had emerged, underscoring deep divisions within the hierarchy.

Alone in his study that night, Pope Leo XIV reviewed headlines announcing a Church transformed.

He acknowledged the turmoil but remained convinced that hidden truths could heal only when exposed.

The doctrine of divine reciprocity, he believed, had the potential to reshape personal relationships, pastoral practice, and even global conflict by emphasizing forgiveness as an active, transformative force.

As Rome settled into darkness, discussions continued in parishes, universities, and homes worldwide.

Whether the revelation would unite or fracture the Church remained uncertain.

What was clear, however, was that Pope Leo XIV had irrevocably altered the conversation about mercy, forgiveness, and human responsibility.

After fifteen centuries of silence, a hidden law of heaven had been spoken aloud, and its consequences were only beginning to unfold.

News

Mel Gibson: “They’re Lying To You About The Shroud of Turin!”

Mel Gibson, the Shroud of Turin, and a Debate That Refuses to End Few religious artifacts in human history have…

PRAY THIS WHEN THE PRIEST ELEVATES THE SACRED HOST – A SACRED SECRET FROM POPE LEO XIV

When Heaven and Earth Meet: Rediscovering the Meaning of the Eucharist For centuries, Christians have gathered around the altar in…

3 THINGS YOU NEED TO START THE NEW YEAR WITH BLESSINGS, PEACE, AND JOY | POPE LEO XIV

At the beginning of a new year, many people instinctively search for luck. They place eggs in rice bowls, hide…

CREMATION OF THE DEAD – WHAT HAPPENS TO THE SOUL? The truth revealed by Pope Leo XIV

Peace is often offered to the dying as comfort, yet Christian teaching insists that truth must come before reassurance. Those…

Mel Gibson Reveals Everything: The Untold Truth Behind The Passion of the Christ! What secrets and challenges lay behind the making of this iconic film? Mel Gibson opens up about the real story behind The Passion of the Christ, sharing insights that will change the way you view the film. Click the article link in the comments to uncover the shocking revelations and the journey that brought this powerful narrative to life!

The Passion of the Christ: A Journey Beyond the Screen Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ” is not just…

Mel Gibson’s Stunning Depiction of the Resurrection: A Vision Like You’ve Never Seen Before!

The Three Days That Changed Everything: From the Cross to the Empty Tomb What really happened between the cross and…

End of content

No more pages to load