Pope Leo XIV Abolishes the Papal Enthronement Ceremony, Shaking Centuries of Vatican Tradition

In the early hours of the morning, long before the sun rose over St.

Peter’s Square, a decision was set in motion that would alter nearly a millennium of Catholic tradition.

At approximately 3:00 a.m., a senior Vatican official stood at the doorway of the papal apartment holding a sealed envelope.

Inside was the final draft of a decree that, by sunrise, would render one of the Church’s oldest ceremonial practices obsolete.

Those who would later learn of the moment described it as one of quiet gravity rather than spectacle—a defining characteristic of Pope Leo XIV’s leadership style.

By the morning of January 3, 2026, the Apostolic Palace felt different.

Monsignor Carlo Ferretti, a veteran Vatican official with nearly four decades of service, sensed it immediately.

The familiar stillness of marble corridors and Renaissance frescoes carried a heavier weight than usual.

Ferretti had been summoned before dawn for what was described only as a matter of extraordinary urgency.

As Master of Pontifical Liturgical Celebrations, he had overseen nearly every major ceremony since the papacy of John Paul II.

Yet this summons felt unlike any before.

When Ferretti arrived, Pope Leo XIV was already awake and dressed—not in traditional papal white, but in a simple black cassock reminiscent of his years as a missionary in Peru.

The Pope stood silently at a window overlooking St.Peter’s Square.

Without preamble, he placed a single document on the desk.

Written in clear, unembellished Latin, the decree announced the immediate abolition of the papal enthronement ceremony.

The implications were staggering.

For more than 900 years, papal authority had been formally inaugurated through elaborate ritual: the golden throne, the triple tiara symbolizing authority, and the procession of cardinals before the faithful.

Under Pope Leo XIV’s decree, all of it would end.

Future popes would begin their ministry with a simple Mass, no different in structure from that celebrated daily in parishes around the world.

Ferretti, reading the document, reportedly felt his legs weaken.

When he finally spoke, his voice betrayed the magnitude of the moment.

The ceremony, he reminded the Pope, dated back to the medieval period and served as a symbolic link to generations of predecessors.

Pope Leo’s response was calm but resolute.

He questioned whether the tradition truly connected the Church to God—or to the earthly kingdoms it once rivaled.

Drawing from his years in rural Peru, the Pope spoke of baptizing children whose families walked for hours through mud, and of burying men who died because medical care was unaffordable.

Against those memories, he contrasted the Church’s gold, silk, and pageantry.

He asked how such displays could be reconciled with the life and teachings of Jesus.

Ferretti, trained to navigate theological crises, found no argument that did not sound hollow.

Resistance was inevitable.

Cardinal Alessandro Marchetti, a leading figure in the Curia and a fierce defender of tradition, had spent months preparing the next enthronement ceremony.

Pope Leo was fully aware of this.

He had read every petition urging preservation of tradition, including Marchetti’s extensive theological defense of the throne as a symbol of Christ’s kingship.

Yet the Pope concluded that sincere belief did not make the argument correct.

The decree was scheduled for announcement at the ordinary consistory later that morning.

There would be no prolonged consultation, no phased rollout—only direct confrontation with the hierarchy.

Ferretti was asked to deliver a simple explanation when questioned: the decree was reversible in theory, but its purpose was moral clarity, not permanence.

By 8:00 a.m., rumors were already circulating through Vatican corridors.

The consistory hall filled quickly with 63 cardinals in Rome at the time, their scarlet cassocks forming a vivid contrast to the gravity of the moment.

Pope Leo entered without notes or prepared remarks, wearing the same black cassock.

He spoke plainly, acknowledging that some would view the decree as necessary reform and others as an attack on sacred tradition.

When Cardinal Marchetti rose to object, his concern centered on continuity and dignity.

Without the enthronement, he asked, how would the Church maintain the authority of the papal office? Pope Leo responded directly, asserting that dignity derived from Christ’s command to serve, not from crowns or thrones.

He spoke of the faithful who filled St.

Peter’s Square at his election, drawn not by spectacle but by hope that the Church still understood human suffering.

The debate extended for more than two hours.

Cardinals from across the world offered contrasting perspectives shaped by their experiences.

Some spoke of how papal grandeur had inspired vocations in distant mission schools.

Others argued that such displays reinforced perceptions of detachment and power.

Pope Leo listened without interruption, absorbing each argument.

When the discussion neared its end, the Pope addressed the assembly with visible emotion.

He spoke of people the cardinals had never met: a mother who apologized for offering only dirty water after he visited her dying son, and a teenager who lost faith after his sister died of a treatable illness.

He stated bluntly that the Church’s visible wealth had become an answer to suffering people never asked for—and that answer, he said, was “insufficient” and “obscene.”

The word lingered heavily in the hall.

A pope had just described a cherished tradition in stark moral terms.

The decree, he said, would stand.

The reaction outside the Vatican was swift.

By midafternoon, the announcement dominated global headlines.

Social media erupted with polarized reactions, while Catholic publications scrambled to issue commentary.

Conservative outlets warned of erosion of identity, while progressive voices hailed a long-overdue realignment with Gospel values.

Small protests formed outside the Vatican that evening.

Demonstrators sang Latin hymns and held images of past popes wearing the triregnum.

Their pain, Vatican officials noted, was genuine.

Inside, Pope Leo met privately with cardinals, offering space for dissent rooted in conscience rather than procedure.

Late that night, Ferretti was again summoned.

This time, the Pope shared a personal journal from his missionary years.

One entry, written after the funeral of a child, asked a single question: “What are we for if not this?” The list that followed mentioned presence, humility, and compassion—but nothing about ceremony.

Pope Leo said the enthronement ritual contradicted that purpose.

The following morning, the Pope celebrated Mass privately.

The homily focused on Jesus sending disciples out with nothing but faith.

No cameras were present.

The decision had been made, and now it would be lived.

In the days that followed, reactions continued to unfold.

Some bishops in poorer regions praised the move, seeing long-standing tension between Vatican symbolism and local realities acknowledged at last.

Others warned of fragmentation.

Donation patterns shifted unevenly.

Historians documented the archived regalia.

The Church adapted, as it always had.

What remained uncertain was the long-term judgment of history.

Pope Leo XIV would be remembered by some as a visionary, by others as a disruptor.

Yet his choice was clear: to strip away accumulated ceremony in favor of visible alignment with mission.

Whether the Church would grow or fracture under that choice remained to be seen.

As evening fell over Rome days later, Ferretti reflected on the enormity of what had occurred.

The throne was gone.

The crown archived.

What remained was an ancient institution forced to confront a fundamental question without the comfort of pageantry: what is the Church for? Pope Leo XIV had placed that question at the center of Catholic life once more, knowing the cost—and accepting it.

News

11 days before they found Jonbenet a victim in a murder case.

The JonBenét Ramsey Case: Unraveling the Mystery 11 Days Before Discovery The tragic case of JonBenét Ramsey, a six-year-old beauty…

BREAKING!!! The Heartbreaking Case of Madeleine McCann

The Disappearance of Madeleine McCann: A Continuing Mystery 16 Years Later In what was once considered one of Europe’s safest…

US SHUTS DOWN Florida Beaches After Mysterious Underwater Discovery Emerged!

Mysterious Underwater Discovery Forces Florida Beach Closures: Could a Hidden Volcano Lurk Beneath the Waves? Florida, known for its sun-drenched…

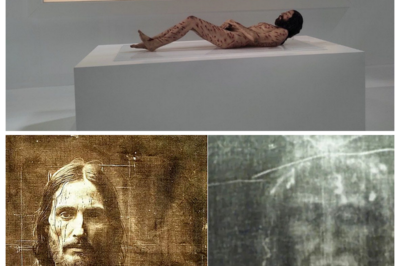

Shroud of Turin: SHOCKING New Evidence Leaves Scientists SPEECHLESS A groundbreaking study has revealed new and shocking evidence on the Shroud of Turin that has left scientists struggling to explain what they are seeing. Using advanced AI analysis and high-resolution imaging, researchers discovered hidden patterns, anomalies, and subtle markings previously invisible to the human eye.

Experts admit that the findings defy conventional understanding of textiles, history, and scientific explanation, reigniting debates about the shroud’s authenticity and origin.

Could this be evidence of ancient unknown techniques, miraculous phenomena, or something even more mysterious? The revelation has sent shockwaves through both the scientific and religious communities.

Click the article link in the comments to uncover the full details and see why scientists were left speechless.

The Shroud of Turin, long one of Christianity’s most debated artifacts, has once again captured global attention following a series…

Was Amelia Earhart Marooned on an Island? New Expedition Launched to Find Her Plane

On June 1, 1937, Amelia Earhart, one of the most celebrated aviators in history, prepared to take off on what…

Pope Leo Xiv’s Shocking Decree: 7 Traditions That Are No Longer Necessary.

In a recent pastoral address, the Church’s leader called upon the faithful to embrace a moment of reflection, discernment, and…

End of content

No more pages to load