The Vatican awoke to an unprecedented revelation in the first days of January.

In the quiet hours just after midnight, an archivist entered the papal library carrying documents that would challenge centuries of ecclesiastical tradition.

The man approached Pope Leo the Fifteenth with hands trembling under the weight of discovery.

Beneath his arm was a leather portfolio containing fragile papyrus fragments, unearthed during routine cataloging in the Vatican Secret Archives.

The sealed container had been hidden for centuries, placed behind a false wall in a sub-level archive, untouched for over two hundred years.

Initial analysis suggested that the material dated to the first century of the Christian era.

The paleography team had worked through the night, using emergency authorization for carbon dating.

The writing on the fragments was in Greek, the script consistent with early Roman ecclesiastical documents.

Each fragment was carefully reconstructed and annotated, revealing signatures attributed to Peter, the Apostle, raising the possibility that these were final instructions intended for the early church in Rome.

On January second, Rome experienced freezing rain that turned the cobblestones of St.

Peter’s Square into reflective surfaces.

Inside the Apostolic Palace, Pope Leo observed the city from his study window, the cold water cascading down the ancient stones.

He had risen before dawn, a habit formed during decades of missionary work in Peru, where his best reflections had always preceded sunrise.

The first months of his papacy had been measured, deliberate, and careful.

As the first American pope, his unexpected election had drawn attention, and he moved through the Vatican with the quiet authority of someone who understood that reform required patience and discernment.

Cardinals from conservative factions watched for missteps, while progressive voices waited for signs of change.

The pontiff focused on one decision at a time, balancing tradition with the subtle implementation of new approaches.

At six forty-five in the morning, Monsignor Claudio Vieieri, deputy prefect of the Vatican Secret Archives, arrived with the portfolio.

His face was pale, the rain darkening his shoulders, and his voice was tight with anticipation.

He explained that the documents had been discovered while cataloging materials from a restoration project.

The fragments, enclosed in a sealed container, appeared to date from the fourth century or earlier.

The carbon dating team had determined a probable date range between sixty and eighty A.D.The handwriting matched known examples from early Christian texts, and the Greek language used in the script was consistent with northern Palestinian dialects of the time.

The pope examined the photographs laid on his desk.

The fragments contained words that had survived in faded but legible sections, and annotations by the restoration team helped reconstruct the context.

The text challenged the hierarchical authority structure later attributed to Peter.

It described the early Christian community as fundamentally equal before Christ, emphasizing leadership as service rather than dominion.

The fragments explicitly rejected the accumulation of wealth, the construction of palaces, and the separation between clergy and laity, characterizing such practices as betrayals of the gospel.

The writing was addressed to the community in Rome, seemingly near the end of Peter’s life, and read as a final instruction or warning.

Key phrases emphasized fellowship, service, and love, culminating in a declaration that no one should be called master, for all are brothers and sisters in faith.

Only the restoration team, two paleographers, the carbon dating technician, and Monsignor Vieieri had seen the fragments.

No one had left the archives since the discovery, and the pontiff ordered absolute silence under the pontifical seal.

Pope Leo understood the implications.

If authenticated and made public, the documents would challenge the foundations of papal authority, episcopal structures, and the broader architecture of church governance.

They suggested that Peter himself had rejected the interpretation of hierarchical primacy later institutionalized by the church.

The pope instructed that the originals be brought to his private chapel and that the restoration team be present for a private examination.

The restoration lab was a controlled environment, lit with specialized lighting and monitored for temperature and humidity.

The eight people awaiting the pope had not slept, standing in tense anticipation.

Dr.Elena Martelli, the senior paleographer, guided him through each fragment.

Her analysis confirmed that the handwriting and language were consistent with first-century scribal practice.

Carbon dating and material analysis triangulated to the period of Peter’s lifetime.

She noted that while absolute proof of authorship was impossible, the content was highly unlikely to be a later forgery.

The message undermined established structures, suggesting that early Christians recognized a radically different model of leadership.

The survival of the fragments suggested that they had been hidden deliberately to prevent destruction, not fabricated to support institutional authority.

The pope reflected on the significance of the findings.

He presented the team with a choice: conceal the documents to preserve existing structures or reveal them and allow truth to disrupt, challenge, and purify.

He emphasized that the discovery was not about destroying the church, but about determining whether its structures served Christ’s mission or human comfort.

A young archivist named Francesca observed that the text called not for dissolution but transformation.

Leadership should be defined by service, not dominion, aligning with the example of Christ, who washed the feet of his disciples.

Pope Leo instructed a full authentication process, involving external experts bound to secrecy.

Linguistic, historical, and forensic examinations were commissioned to ensure that every aspect of the fragments could be verified beyond reasonable doubt.

Over the following three days, experts arrived discreetly at the Vatican.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(999x0:1001x2)/pope-leo-xiv-050825-9-1f856aa9fabd4f97a913fde4974eb4f7.jpg)

Paleographic, linguistic, and historical analyses were conducted alongside forensic testing.

The pope maintained his usual schedule, attending morning mass, receiving audiences, and meeting with curial officials, while keeping the ongoing authentication entirely confidential.

On the evening of January fourth, the final report arrived.

It concluded with ninety-three percent confidence that the fragments originated in Rome between sixty and seventy-five A.D., were written in the hand attributed to Simon Peter, and represented an authentic first-century apostolic text.

No evidence of forgery, later addition, or manipulation was detected.

Pope Leo spent two hours in private prayer before the crucifix, reflecting on the magnitude of the discovery.

He then instructed Monsignor Vieieri to schedule a press conference for January sixth, inviting all major international media and Catholic and secular journalists.

He refused to consult with cardinals or develop a strategy to manage reactions, insisting that the truth must be presented plainly.

Word of the press conference spread rapidly within the Vatican, creating a climate of speculation, tension, and anticipation.

Senior cardinals demanded meetings, but the pope provided no information, emphasizing that the world would learn the truth directly from him.

The evening before the conference, Pope Leo studied the photographs of the papyrus fragments.

He read Peter’s words slowly, translating them into modern language.

The text emphasized equality, service, and humility, rejecting hierarchies, accumulation of wealth, and positions of power.

The pope internalized the message, understanding that its implications would challenge every layer of church governance and the assumptions of the faithful.

On January sixth, the press room was packed beyond capacity.

Over four hundred journalists, photographers, and camera operators gathered, filling every available space.

Pope Leo entered at ten o’clock wearing simple white vestments, carrying a thin folder, and approached the podium without ceremony.

He greeted the assembly in Italian, Spanish, and English, bringing the room to silence.

He announced the discovery of a sealed container in the Vatican archives containing fragments of a letter from the Apostle Peter to the church in Rome.

The letter had been authenticated by multiple independent experts.

Its content challenged assumptions about hierarchical structures, clerical authority, and wealth accumulation within the institutional church.

Peter described a community defined by radical equality, leadership through service, and warnings against the construction of structures later institutionalized as hierarchical authority.

The announcement ignited a storm of questions.

The pope responded calmly and deliberately, stating that the full text, translations, and authentication documentation would be released immediately.

The fragments themselves would be displayed in a public exhibition the following week.

When asked whether he considered the current structure of the church illegitimate, Pope Leo responded that the discovery required reflection on whether existing structures served the gospel or obscured it.

He affirmed that he would lead the church through this examination rather than away from it, acknowledging that the truth would disturb those who profited from its absence and liberate those who had long awaited clarity.

Journalists asked if he anticipated schism.

Pope Leo replied that he was prepared for honesty and that any division would arise from choices made by those confronted with Peter’s message.

He emphasized that the church must decide whether it genuinely followed Christ or merely admired Peter.

Over forty minutes, he answered every question with calm determination, reinforcing that Peter’s voice could not be managed or silenced, and that the church must confront the implications of his words.

In the hours after the press conference, the Vatican was in turmoil.

Cardinals convened emergency meetings, factions formed, and debates erupted regarding the legitimacy of the announcement and the authenticity of the documents.

Critics challenged the pope’s judgment, while supporters lauded his commitment to transparency and truth.

International media amplified the story, and social media buzzed with discussion, analysis, and controversy.

Pope Leo remained focused, reflecting privately on Peter’s final lines, which emphasized service, humility, and the radical equality of believers.

He understood that the church had been forced to confront the essence of its mission.

Pope Leo returned to his study, holding the photograph of Peter’s message.

The rain had stopped, and the stones of St.

Peter’s Square gleamed under the floodlights.

He considered the responsibility now resting on his shoulders, the moral and spiritual weight of the decision to reveal the fragments, and the necessity of leading the church through its consequences.

He addressed the apostle directly in the quiet room, acknowledging the long journey of faith and the call to act according to the truth that had been entrusted to him.

The discovery marked a new chapter for the Vatican, challenging the faithful to reflect on the purpose of their community and the meaning of leadership grounded in service rather than dominion.

The events of early January represented a pivotal moment for the Catholic Church, combining historical scholarship, religious authority, and moral courage.

Pope Leo’s decision to reveal the papyrus fragments transformed centuries of understanding, inviting believers and leaders alike to examine whether institutional structures reflected the teachings of Christ or merely human ambition.

The fragments provided a direct line to the voice of Peter, a challenge and a guide for modern leadership.

The pope’s actions demonstrated a commitment to truth, transparency, and faith, reshaping the church’s engagement with history, scholarship, and the responsibilities of spiritual authority.

News

JRE: “Scientists Found a 2000 Year Old Letter from Jesus, Its Message Shocked Everyone”

There’s going to be a certain percentage of people right now that have their hackles up because someone might be…

If Only They Know Why The Baby Was Taken By The Mermaid

Long ago, in a peaceful region where land and water shaped the fate of all living beings, the village of…

If Only They Knew Why The Dog Kept Barking At The Coffin

Mingo was a quiet rural town known for its simple beauty and close community ties. Mud brick houses stood in…

What The COPS Found In Tupac’s Garage After His Death SHOCKED Everyone

Nearly three decades after the death of hip hop icon Tupac Shakur, investigators searching a residential property connected to the…

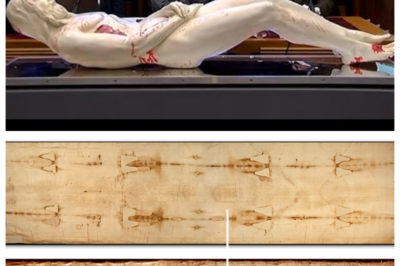

Shroud of Turin Used to Create 3D Copy of Jesus

In early 2018 a group of researchers in Rome presented a striking three dimensional carbon based replica that aimed to…

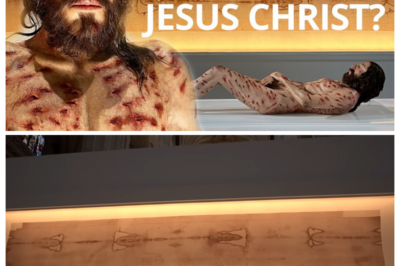

Is this the image of Jesus Christ? The Shroud of Turin brought to life

**The Shroud of Turin: Unveiling the Mystery at the Cathedral of Salamanca** For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has captivated…

End of content

No more pages to load