The idea of the fourth dimension has fascinated scientists, philosophers, and the general public for generations.

It carries an almost mystical reputation, often misunderstood as a hidden realm, an alternate universe, or a supernatural space beyond human perception.

In reality, the concept of dimensions is far more precise, grounded in mathematics and physics rather than imagination.

Understanding what a dimension truly is requires setting aside popular misconceptions and returning to a fundamental question: how do we describe position, structure, and change in the universe?

At its most basic level, a dimension is not a place but a requirement for description.

A one-dimensional system needs only a single number to specify a position.

A straight line is the simplest example.

If a point lies somewhere along a ruler, one measurement is enough to identify its location.

This is why it is called one-dimensional.

Introduce a second independent direction, perpendicular to the first, and one number is no longer sufficient.

Now two coordinates are required, such as length and width, to locate a point on a flat surface.

This creates a two-dimensional space.

Add a third independent direction, perpendicular to the first two, and the familiar three-dimensional world emerges.

Height joins length and width, and three numbers become necessary to describe position.

Everything we interact with daily exists within this three-dimensional framework.

Objects have volume, shape, and orientation, all determined by these three spatial dimensions.

From this perspective, a fourth dimension would simply be another independent direction, one that cannot be reduced or derived from the existing three.

This is where intuition begins to fail.

While it is easy to imagine moving left or right, forward or backward, up or down, it becomes impossible to picture a direction that is perpendicular to all three simultaneously.

Human perception evolved to navigate a three-dimensional environment, and as a result, the brain lacks the sensory framework to visualize higher spatial dimensions.

This limitation is not a failure of intelligence but a consequence of biology.

Despite this, mathematics has no difficulty defining higher dimensions.

A four-dimensional space can be described precisely using four coordinates instead of three.

Visualization is not required for mathematical consistency.

In fact, many mathematical structures exist in dimensions far beyond what can be imagined, and they remain internally logical and rigorously defined.

The challenge arises only when attempting to translate these abstract concepts into mental images.

One common tool for bridging this gap is analogy.

Just as a three-dimensional object casts a two-dimensional shadow, a four-dimensional object would cast a three-dimensional projection.

This idea allows mathematicians and physicists to study higher dimensions indirectly.

A well-known example is the tesseract, a four-dimensional analogue of a cube.

When projected into three-dimensional space, it appears as a cube within a cube, connected by edges that represent the extra dimension.

Although this projection is not the object itself, it provides insight into how higher-dimensional geometry behaves.

Physics introduces an additional layer of complexity by redefining what the fourth dimension represents.

In Einstein’s theory of relativity, the fourth dimension is not an additional spatial direction but time.

Space and time are unified into a single structure known as spacetime.

In this framework, an event is not defined solely by where it occurs, but also by when it occurs.

Three spatial coordinates and one temporal coordinate are required to fully describe any event in the universe.

This treatment of time as a dimension is not symbolic or metaphorical.

It has measurable consequences.

Time behaves differently depending on speed and gravity.

Objects moving at high velocities experience time more slowly relative to stationary observers.

Similarly, strong gravitational fields slow the passage of time.

These effects have been confirmed experimentally and must be accounted for in technologies such as GPS systems, which rely on precise timing to function accurately.

Understanding time as a dimension also clarifies why it cannot be avoided.

All objects move through time continuously, regardless of whether they move through space.

Even when stationary, time progresses.

Motion through space simply alters the rate at which time is experienced.

This makes time fundamentally different from spatial dimensions, yet inseparable from them within the structure of spacetime.

Another idea often associated with higher dimensions is curvature.

In everyday experience, space appears flat.

Parallel lines remain parallel, and geometry behaves according to familiar rules.

However, on cosmic scales, space may be curved.

Curvature does not require an external higher-dimensional space to exist; it can be intrinsic.

A two-dimensional surface, like the surface of a sphere, can be curved without needing to bend into a third dimension from its own perspective.

Similarly, three-dimensional space can be curved without requiring a fourth spatial dimension as a container.

Modern cosmology suggests that the universe is very close to geometrically flat, though slight curvature remains a theoretical possibility.

This curvature, if present, would affect how light travels over vast distances and how the universe evolves over time.

Importantly, this does not imply that each dimension individually curves into the next, nor does it suggest a hierarchy of nested dimensions.

These interpretations often arise from metaphor rather than physics.

The notion that dimensions stack infinitely, with each higher dimension containing the lower ones, is a speculative idea with no experimental support.

While certain theories in high-energy physics, such as string theory, propose additional spatial dimensions, these dimensions are not extended like the ones we experience.

They are predicted to be extremely small, compactified at scales far beyond direct observation.

Their existence remains hypothetical and unconfirmed.

Misunderstandings about dimensions often stem from conflating mathematical abstraction with physical reality.

Mathematics allows for infinite dimensions, infinite sets, and structures that defy physical intuition.

Nature, however, is constrained by observation and experiment.

Not every mathematically consistent idea corresponds to something physically real.

This distinction is critical when discussing concepts like infinity, higher dimensions, or the ultimate structure of the universe.

Conceptual explanations play an important role in making complex ideas accessible, but they have limits.

Many areas of modern physics cannot be fully captured through analogy or visualization.

Quantum field theory, for example, relies on mathematical formalisms that have no direct sensory equivalent.

Attempts to simplify these concepts often involve metaphors that are useful but fundamentally inaccurate.

Understanding physics at a deep level eventually requires engaging with the mathematics itself.

This does not mean conceptual thinking is useless.

On the contrary, it provides intuition, context, and motivation.

It helps frame questions and identify relationships.

However, conceptual understanding should be treated as a guide rather than a substitute for formal reasoning.

The danger lies in mistaking analogy for truth, or intuition for proof.

The discussion of the fourth dimension highlights this balance.

It demonstrates how far human curiosity can reach and how easily imagination can outpace evidence.

At the same time, it shows the power of careful reasoning.

By grounding abstract ideas in definitions, mathematics, and experimental results, it becomes possible to explore realms far beyond direct experience without losing rigor.

Ultimately, the fourth dimension is not a mystical gateway or a hidden world waiting to be discovered.

It is a precise concept with different meanings depending on context.

In mathematics, it is simply another degree of freedom.

In physics, it is time, woven inseparably into the fabric of spacetime.

In cosmology and theoretical physics, it is a tool for exploring possibilities that push the boundaries of what is known.

The enduring fascination with higher dimensions reflects a deeper human impulse: the desire to understand reality beyond appearances.

Even when visualization fails, reasoning continues.

Even when intuition breaks down, mathematics provides structure.

The fourth dimension reminds us that the universe is not obligated to conform to how it feels, only to how it works.

And in that realization lies both humility and wonder.

News

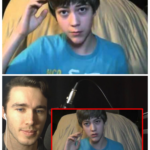

Kid Explains 4th Dimension Then Goes Missing: What Happened to XKCDHatGuy?

Approximately twelve years ago, a modest YouTube upload quietly became one of the most enduring pieces of educational content in…

“That’s Jesus!” A Nuclear Engineer’s Fascinating Experiment on The Shroud of Turin w/ Bob Rucker

The Shroud of Turin has remained one of the most enduring and controversial objects in human history, suspended between faith,…

JonBenét Ramsey: The Garrote Mystery – Was She Already Dead When They Applied It?

On December 26, 1996, at approximately 1:13 p.m., John Ramsey discovered the body of his six-year-old daughter JonBenét in a…

Christian Pulisic after dating actress Sydney Sweeney

Christian Pulisic Addresses Dating Rumors with Sydney Sweeney In recent days, soccer star Christian Pulisic has taken a firm stand…

Richard Smallwood Dies at 77: Gospel Legend’s Hidden Truth

When Richard Smallwood passed away in the early hours of the morning, the loss reverberated far beyond the boundaries of…

Bob Lazar Details His UFO Experiences on Joe Rogan

For more than three decades, Bob Lazar’s account of working on recovered non-human technology has existed at the edge of…

End of content

No more pages to load