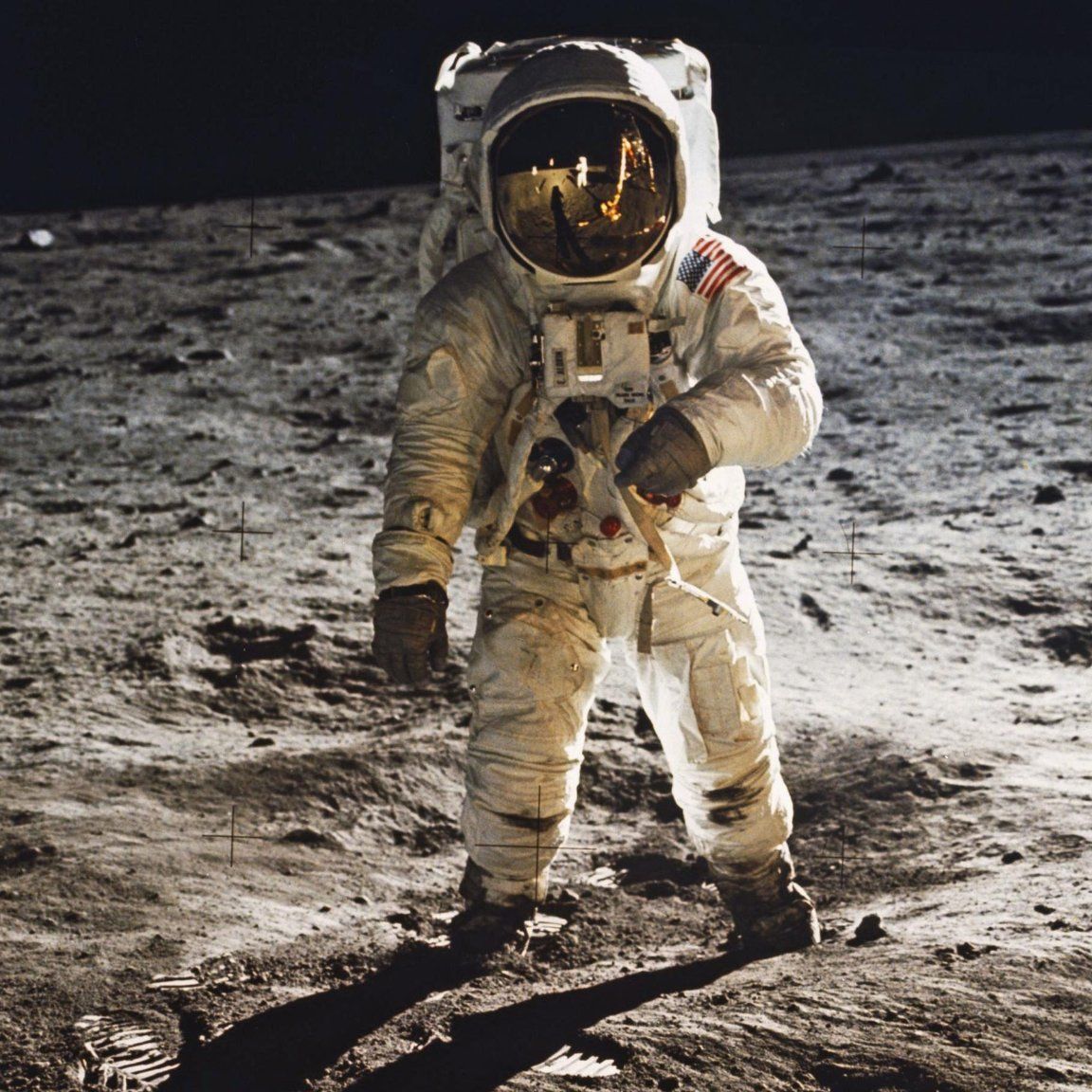

For more than half a century, one question has lingered quietly behind every rocket launch and space anniversary: if humanity reached the Moon in 1969, why did it not return? The absence of astronauts on the lunar surface since 1972 has fueled speculation, myth, and conspiracy, yet the most convincing explanation is neither dramatic nor secretive.

It is political, economic, and deeply human.

The story of why we left the Moon behind reveals less about hidden dangers in space and more about how ambition, power, and priorities shape exploration.

At the center of many modern interpretations is John C.Mather, a Nobel Prize–winning astrophysicist and longtime NASA insider.

Mather, best known for his work confirming the Big Bang and later guiding the James Webb Space Telescope, has often been misquoted as hinting at dark truths about the Moon.

In reality, his message has been consistent and surprisingly plain.

The problem with Apollo, he argued, was not that it failed, but that it was never designed to last.

Planting flags and collecting samples achieved a political objective, but it did not create a sustainable presence.

Without permanence, the momentum was destined to collapse.

Mather’s view echoes that of another Nobel laureate from an earlier era, chemist Harold Urey.

During the planning stages of Apollo, Urey strongly believed the Moon might contain substantial water locked within its rocks.

This idea mattered enormously.

Water is not only essential for life; it can be split into oxygen and hydrogen for breathing and fuel.

If the Moon held accessible water, it could support long-term human activity and serve as a stepping stone deeper into the solar system.

Urey championed this vision publicly, lending scientific credibility to the idea that the Moon was more than a symbolic target.

But science has an inconvenient habit of correcting optimism.

When lunar samples returned from Apollo missions, the evidence was clear.

The Moon was far drier than hoped.

Urey acknowledged this openly, even though it weakened the argument for continued exploration.

His intellectual honesty carried an unintended consequence: the Moon lost much of its practical value in the eyes of policymakers.

Without resources that justified permanent investment, lunar missions became harder to defend once their symbolic purpose was fulfilled.

To understand why this mattered, Apollo must be seen in its historical context.

The Moon landings were never purely about exploration.

They were a direct product of the Cold War, when technological achievement functioned as geopolitical theater.

The launch of Sputnik by the Soviet Union in 1957 had shaken American confidence and triggered fear that space dominance equaled military dominance.

In response, the United States committed itself to a goal so visible and dramatic that failure would be unthinkable: landing humans on the Moon.

That fear-driven urgency explains Apollo’s astonishing speed.

NASA was given enormous funding, political insulation, and a single, non-negotiable objective.

Efficiency mattered less than victory.

Risk was accepted, timelines were compressed, and costs were tolerated because the stakes extended far beyond science.

When Apollo 11 succeeded in July 1969, the objective was achieved in front of the entire world.

In Cold War terms, the United States had won.

The consequences were immediate.

The Soviet Union quietly abandoned its own crewed lunar ambitions, removing the very pressure that had justified Apollo’s scale.

Without a rival to race, repeated lunar landings no longer carried the same political weight.

To lawmakers, each new mission began to look less like a triumph and more like an expensive repetition.

Public attention followed the same pattern.

Television ratings declined, and even as later Apollo missions conducted far more extensive scientific work, they struggled to capture the imagination ignited by the first landing.

The financial reality was impossible to ignore.

Apollo cost approximately 25 billion dollars in its own time, well over 250 billion in today’s terms.

At its peak, NASA consumed nearly four percent of the entire U.S.federal budget.

Such spending was sustainable only under extraordinary circumstances.

By the early 1970s, those circumstances had vanished.

The Vietnam War was escalating, draining resources and political capital.

Domestic priorities demanded attention.

Space, once urgent, now appeared optional.

Budget cuts followed swiftly.

Apollo missions 18, 19, and 20 were canceled despite the fact that hardware existed and astronauts were trained.

The decision was not driven by fear, secrecy, or technical failure.

It was driven by arithmetic.

Lunar missions no longer solved a political problem, and they demanded an extraordinary amount of money.

In contrast, a new vision promised affordability and continuity: the Space Shuttle.

The Shuttle was marketed as a reusable system that would make space routine.

It shifted NASA’s focus toward low Earth orbit, satellite deployment, and infrastructure closer to home.

Politically, it was easier to justify.

Economically, it fit annual budgets.

Strategically, it marked a decisive turn away from the Moon.

Every dollar invested in the Shuttle was a dollar not spent on rebuilding lunar capability.

What followed was not just the end of missions, but the dismantling of an entire ecosystem.

Apollo was not a single machine or set of blueprints.

It was a vast industrial network involving more than 400,000 people across thousands of companies.

NASA itself built little directly; contractors did.

When funding collapsed, layoffs were immediate and permanent.

Engineers moved on.

Skilled technicians retired.

Factories shut down.

Specialized tooling was scrapped or repurposed.

Crucially, much of Apollo’s knowledge was never fully documented.

It lived in experience, in informal problem-solving, and in lessons learned through failure.

When the workforce dispersed, that knowledge dispersed with it.

Decades later, engineers searching for Saturn V documentation discovered gaps not because of secrecy, but because no one expected the designs to be needed again.

Restarting lunar exploration thus became more expensive than continuing it would have been.

New safety standards, new materials regulations, and new expectations meant old designs could not simply be copied.

Entire supply chains had to be rebuilt.

Every assumption had to be tested again.

The Moon did not become unreachable, but it became distant in a different way—separated by lost momentum.

This long absence created fertile ground for speculation.

When people see a story interrupted, they look for hidden endings.

Myths about alien structures, secret treaties, or undisclosed dangers flourished in the vacuum left by silence.

Yet modern lunar science offers no evidence to support such claims.

Multiple nations have mapped the Moon in extraordinary detail.

Its far side is no longer hidden, and its surface has been examined by independent researchers worldwide.

That does not mean the Moon is fully understood.

Phenomena such as transient lunar flashes, unusual seismic behavior, and uneven geological composition remain active areas of research.

These mysteries are real, but they are scientific questions, not proof of concealment.

Robotic missions can study them cheaply and safely, which further reduced the urgency of sending humans back during the late twentieth century.

The situation has begun to change only recently.

NASA’s Artemis program represents a fundamentally different approach from Apollo.

Instead of racing for a symbolic first, Artemis aims to establish a sustained presence.

The focus on the Moon’s south pole, where water ice has been confirmed, directly addresses the resource problem that undermined earlier ambitions.

Water transforms the Moon from a destination into infrastructure.

Yet Artemis also reflects the lessons learned from Apollo’s collapse.

Progress is slower, oversight is heavier, and international and commercial partnerships complicate decision-making.

Safety standards are higher, political tolerance for failure is lower, and funding must survive multiple administrations.

This makes the process less dramatic, but potentially more durable.

In this context, John C.

Mather’s words take on their true meaning.

When he spoke of returning to the Moon “to stay,” he was not hinting at danger or secrets.

He was acknowledging history.

Exploration driven by rivalry fades when the rivalry ends.

Exploration driven by intention requires patience, planning, and sustained commitment.

Humanity did not abandon the Moon because it was afraid of what it found there.

It walked away because the system that made going possible no longer existed.

Politics changed.

Money moved elsewhere.

Infrastructure vanished.

What remains is not a mystery, but a lesson.

Reaching the Moon was never the hardest part.

Staying there was.

News

Black CEO Denied First Class Seat – 30 Minutes Later, He Fires the Flight Crew

You don’t belong in first class. Nicole snapped, ripping a perfectly valid boarding pass straight down the middle like it…

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 7 Minutes Later, He Fired the Entire Branch Staff

You think someone like you has a million dollars just sitting in an account here? Prove it or get out….

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 10 Minutes Later, She Fires the Entire Branch Team ff

You need to leave. This lounge is for real clients. Lisa Newman didn’t even blink when she said it. Her…

Black Boy Kicked Out of First Class — 15 Minutes Later, His CEO Dad Arrived, Everything Changed

Get out of that seat now. You’re making the other passengers uncomfortable. The words rang out loud and clear, echoing…

She Walks 20 miles To Work Everyday Until Her Billionaire Boss Followed Her

The Unseen Journey: A Woman’s 20-Mile Walk to Work That Changed a Billionaire’s Life In a world often defined by…

UNDERCOVER BILLIONAIRE ORDERS COFFEE sa

In the fast-paced world of business, where wealth and power often dictate the rules, stories of unexpected humility and courage…

End of content

No more pages to load