The Sudarium of Oviedo, the Shroud of Turin, and the Challenge to Medieval Dating

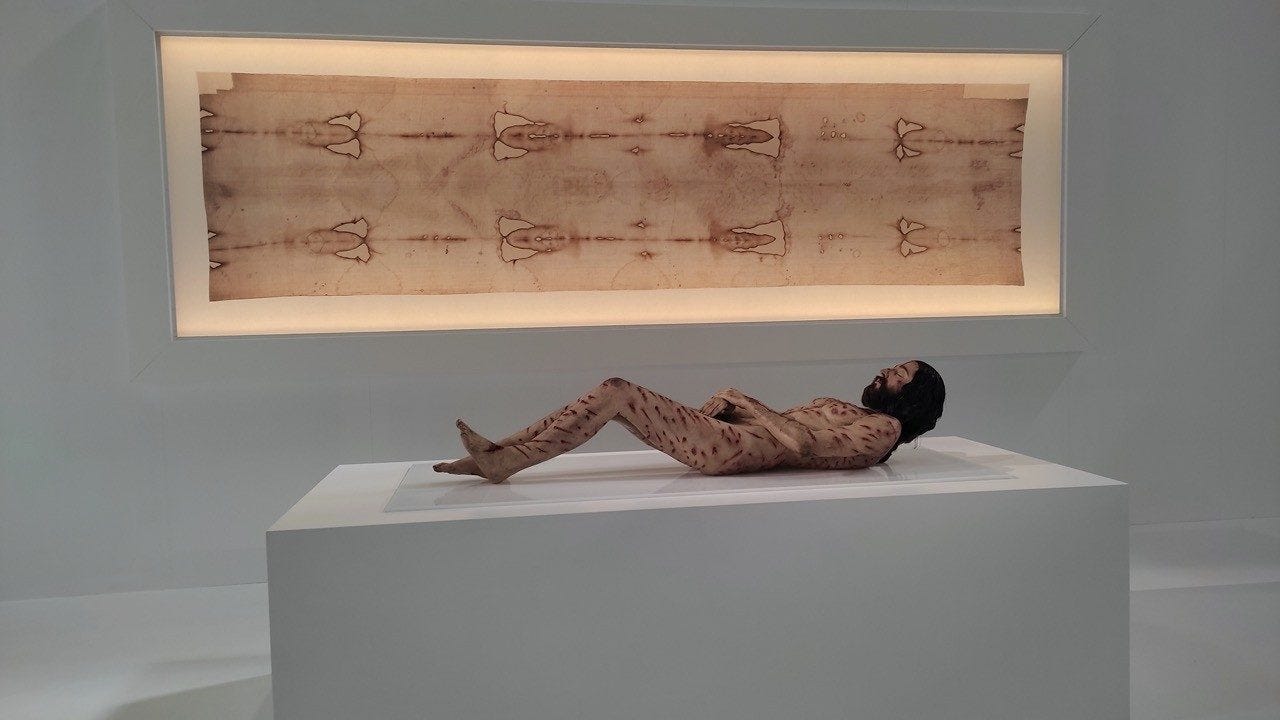

Among the most debated artifacts in Christian history, the Shroud of Turin has long occupied a controversial position at the intersection of faith, science, and history.

While radiocarbon testing conducted in 1988 placed the Shroud’s linen in the medieval period, a growing body of interdisciplinary scholarship argues that this conclusion is incompatible with other physical, historical, and forensic evidence.

Central to this debate is another, far less known relic: the Sudarium of Oviedo.

.

When studied together, proponents argue, the Sudarium and the Shroud form a coherent historical and forensic record that significantly challenges the medieval forgery hypothesis.

The Sudarium of Oviedo is a cloth traditionally identified with the “face cloth” mentioned in the Gospel of John, distinct from the larger burial shroud.

According to Jewish burial customs of the first century, a separate cloth would have been used to cover the face of a deceased person immediately after death, especially in cases involving trauma and bleeding.

The Sudarium, unlike the Shroud, bears no body image but contains extensive bloodstains.

These stains are the primary focus of scientific study and comparison.

Historical documentation places the Sudarium in Jerusalem during Late Antiquity, followed by its transfer through North Africa and into Spain, where it has been preserved in Oviedo since at least the late eighth century.

Multiple written sources trace its movement ahead of the Islamic conquests, firmly anchoring its presence centuries before the earliest possible medieval date proposed for the Shroud.

Even critics who remain skeptical of first-century origins generally concede that the Sudarium’s provenance reaches back to at least the sixth century.

Scientific analysis of the Sudarium has revealed several striking features.

The blood on the cloth has been identified as type AB, a relatively rare blood group that also appears on the Shroud of Turin.

Furthermore, forensic studies indicate that the blood is postmortem, meaning it flowed after death rather than during life.

The blood composition includes a mixture of hemoglobin and pulmonary edema fluid, consistent with death by asphyxiation or severe trauma—precisely the physiological conditions expected in Roman crucifixion.

What has drawn particular attention is the precise correspondence between bloodstain patterns on the Sudarium and wounds visible on the face of the Shroud figure.

When the two cloths are digitally overlaid and aligned by facial landmarks such as the nose, researchers report a one-to-one match in size, orientation, and distribution of blood flows.

Stains around the mouth, nose, beard area, and forehead correspond closely, including distinctive flow patterns that suggest gravity-driven movement of blood under changing body positions.

These patterns have been reconstructed through forensic modeling.

According to the reconstruction, the cloth was first placed around the head of a deceased man while the body remained upright, consistent with removal from a cross.

Later, the body was laid face down for a period, allowing blood to flow upward along the nose and pool on the forehead.

Finally, the body was briefly turned face up, during which pressure marks consistent with fingers pinching the nose appear to have formed.

These stages align closely with what is known of Jewish burial practices and the limited time window described in the Gospel accounts.

The implications of this correspondence are significant.

If the Sudarium and the Shroud wrapped the same individual at different moments, then both artifacts must originate from the same historical context.

Since the Sudarium’s presence is securely attested centuries before the medieval period, proponents argue that the Shroud cannot reasonably be a fourteenth-century creation.

Any medieval forger would have had to know of the Sudarium, have access to it, and somehow reproduce bloodstain patterns with anatomical and forensic precision centuries ahead of modern forensic science.

The question of radiocarbon dating therefore becomes central.

Critics of the 1988 tests have long pointed to methodological concerns, including sample location, possible contamination, and the Shroud’s documented exposure to fire, water, smoke, and repairs.

The Sudarium comparison adds another dimension: if carbon dating places the Shroud in the Middle Ages, yet the Shroud demonstrably matches a cloth known to exist in antiquity, then at least one line of evidence must be flawed.

Advocates of authenticity argue that the carbon dating results should be reconsidered rather than treated as conclusive.

Beyond the face cloth, the Shroud itself presents additional anomalies that resist simple explanations.

The image on the Shroud is not painted, dyed, or scorched.

It contains three-dimensional information encoded in image intensity, something unknown in medieval art.

The wounds visible on the body correspond with Roman crucifixion practices in ways that were not fully understood until modern times.

Notably, the nail wounds appear in the wrists rather than the palms, consistent with anatomical requirements for supporting body weight—contrary to most historical artwork, which places nails through the hands.

The Shroud also depicts extensive scourge marks across the body.

Analysis suggests over a hundred lashes delivered by a Roman flagrum, a whip fitted with weighted metal tips.

Each strike left multiple wounds, producing hundreds of injuries across the front and back of the body.

The distribution and angle of these marks imply the presence of more than one executioner and align with known Roman punitive methods.

Such details would have required extraordinary anatomical knowledge to fabricate convincingly.

Another notable feature is the wound in the side of the body.

The Shroud shows a postmortem spear wound between the ribs, consistent with penetration of the pericardial sac surrounding the heart.

The separation of blood and clear fluid visible in the wound corresponds to the “blood and water” described in the Gospel of John and matches known physiological effects following traumatic death.

As with the Sudarium, the blood flow characteristics indicate the wound was inflicted after death, not before.

The Shroud also reveals numerous puncture wounds across the scalp, suggesting that the so-called crown of thorns was not a simple circlet but a cap-like arrangement covering the entire head.

Botanical studies identify the thorns as consistent with plants native to the Jerusalem area.

The severity and distribution of these wounds point to prolonged bleeding, reinforcing the conclusion that the man depicted suffered extreme trauma beyond standard execution.

Taken together, these features form a cumulative case rather than a single decisive proof.

Supporters of authenticity argue that while any one detail might be disputed, the convergence of forensic pathology, historical documentation, textile science, and comparative analysis with the Sudarium makes a medieval forgery increasingly implausible.

The level of precision required would exceed what was possible with the artistic, medical, and scientific knowledge of the Middle Ages.

From a historical perspective, the uniqueness of the execution depicted also stands out.

While crucifixion was a common Roman punishment, the specific combination of scourging severity, head trauma, wrist nailing, side piercing, and rapid death is unparalleled in surviving records.

This aligns closely with the Gospel narratives describing the execution of Jesus of Nazareth during Passover under Roman authority.

Importantly, proponents emphasize that belief in authenticity does not rest solely on faith.

Rather, they argue that the Shroud and the Sudarium represent rare cases where religious relics are also scientific artifacts—objects that can be tested, analyzed, and debated using empirical methods.

This distinguishes them from many other relics whose authenticity relies primarily on tradition or devotional belief.

Ultimately, the debate surrounding the Shroud of Turin and the Sudarium of Oviedo reflects a broader question about how historical truth is assessed.

It challenges scholars to weigh conflicting evidence carefully and to remain open to revising conclusions in light of new data.

Whether one views these cloths as sacred relics or extraordinary historical artifacts, their combined evidence continues to provoke serious questions about the limits of medieval explanations and the enduring mysteries surrounding one of history’s most influential figures.

In that sense, the Sudarium and the Shroud do not merely point backward to the past.

They continue to function as catalysts for inquiry, compelling modern observers to reconsider assumptions about history, science, and the origins of Christianity itself.

News

Pope Francis: “Ethiopian Bible Proves We’ve Been Misled About Christianity and I Brought Proof” What If One of the Oldest Bibles on Earth Changes Everything We Thought We Knew About Christianity? Hidden for centuries, the Ethiopian Bible contains ancient books, forgotten teachings, and shocking differences that challenge mainstream Christian history. Why was this version ignored for so long, and what does it reveal that the modern Bible doesn’t? The answer may reshape faith, history, and belief itself — click the article link in the comments to uncover the truth.

The Ethiopian Orthodox Church and the Ancient Bible That Challenges Common Assumptions About Christianity The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church stands…

When Jesus’ TOMB Was Opened For The FIRST Time, This is What They Found

The Unveiling of Jesus Christ’s Tomb: History, Discovery, and Impact The tomb of Jesus Christ has long stood as one…

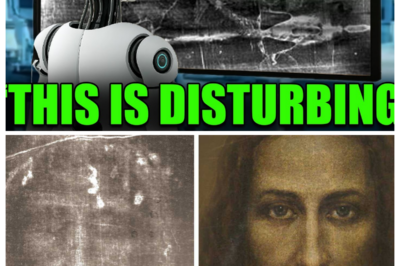

What AI Just Found in the Shroud of Turin — Scientists Left Speechless

For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has remained an enigma that fascinates both believers and scientists. This fourteen-foot-long linen cloth,…

What AI Just Decoded in the Shroud of Turin Is Leaving Scientists Speechless

For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has fascinated and confounded both believers and skeptics. This nearly 14-foot-long piece of linen,…

UNSEEN MOMENTS: Pope Leo XIV Officially Ends Jubilee Year 2025 by Closing Holy Door at Vatican

Pope Leo XIV Officially Closes the Holy Door: A Historic Conclusion to Jubilee Year 2025 On the Feast of the…

Pope Leo’s Former Classmate WARNS: “This is NOT the Catholic Church”

The Catholic Church, in recent years, has faced debates and controversies that have shaken its traditional structures and practices, particularly…

End of content

No more pages to load