Ten years ago, a scientific decision in northern Mexico was widely viewed as reckless.

A small herd of bison was released into an arid landscape marked by compacted soil, sparse vegetation, and the near absence of surface water.

There was no supplemental feeding, no artificial water sources, and no constant human oversight.

Critics believed the animals would fail within months.

The environment appeared too degraded to support large grazers, let alone allow them to alter the land itself.

A decade later, the same landscape told a remarkably different story.

Long before modern borders, highways, and fencing divided North America, bison shaped the continent.

Historical estimates suggest that more than sixty million animals once moved across the plains from present day Canada to northern Mexico.

These herds were not merely inhabitants of the land.

They functioned as mobile ecosystems.

Their hooves aerated soil, their grazing patterns encouraged plant diversity, and their seasonal movements supported predators, birds, insects, and human communities.

Indigenous societies lived in close relationship with bison for centuries.

The animals provided food, clothing, shelter materials, and tools.

More importantly, they represented balance.

The relationship was reciprocal rather than extractive.

Human survival was linked directly to the health of the herds and the grasslands they sustained.

This balance collapsed with European expansion.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, bison were reduced from a foundation species to a commercial commodity.

Industrial demand for hides and other products drove mass sl*ughter on an unprecedented scale.

Railroad expansion made transport easy, while entire carcasses were left to decay after only select parts were removed.

This was not subsistence hunting but systematic elimination.

By the late nineteenth century, bison populations had fallen from tens of millions to only a few hundred animals in the wild.

In Mexico, the species disappeared entirely.

Their removal triggered consequences that extended far beyond the loss of a single animal.

Grasslands began to unravel.

Soil compacted.

Native plants declined.

Entire ecological networks weakened or vanished.

Without bison, the land slowly hardened.

Their hooves had once broken surface crusts, allowing rain to infiltrate the ground.

Without that disturbance, water ran off rather than soaking in.

Grasses failed to regenerate, and thorny shrubs spread.

Streams that once flowed seasonally became intermittent or dry.

What had been a living system entered a long decline.

Livestock replaced bison in many regions, but cattle grazed differently.

They lingered, overused specific areas, and accelerated erosion.

Soil fertility declined further.

Prairie dog colonies collapsed as the ground became too compact for burrowing.

With their disappearance came the loss of species that depended on them, including burrowing birds and specialized predators.

The plains grew quieter.

By the early twenty first century, northern Mexico faced advanced desertification.

Attempts to reverse the damage relied on human engineering.

Grass seeding, irrigation projects, and mechanical soil treatments were attempted repeatedly.

None produced lasting results.

The underlying processes that once sustained the grasslands were still missing.

In two thousand nine, a small group of conservation scientists proposed an alternative approach.

Instead of forcing recovery through technology, they suggested restoring the species that originally maintained the system.

Twenty three bison were transported from conservation herds in the United States to a protected area in Chihuahua.

The animals were released without long term human support.

Public reaction was skeptical.

Ranchers feared competition with livestock.

Officials questioned the use of resources.

Observers predicted failure.

Yet the bison adapted.

They moved constantly, grazed selectively, and searched for moisture beneath the surface.

Their behavior began altering the land almost immediately.

Hoof action cracked the hardened soil.

Manure enriched nutrient poor ground with nitrogen and other essential elements.

Seeds carried in fur and waste spread across disturbed areas.

When rains arrived, water infiltrated rather than running off.

Green shoots appeared where bare ground had persisted for years.

Within the first year, vegetation increased measurably.

Insects returned, followed by birds.

By the third year, calves were being born, indicating that the herd was not only surviving but reproducing successfully.

The land responded faster than most models had predicted.

One of the most significant indicators of recovery was the return of prairie dogs.

These animals rely on open grasslands and loose soil.

Their burrowing further aerated the ground and created microhabitats.

Prairie dog colonies support dozens of other species by providing shelter and altering vegetation structure.

With prairie dogs came their ecological partners.

Burrowing owls returned, using abandoned tunnels for nesting.

Black footed ferrets followed, drawn by renewed prey availability.

Each species represented another link restored in a long broken chain.

Scientists recognized the pattern as a trophic cascade driven by a keystone species.

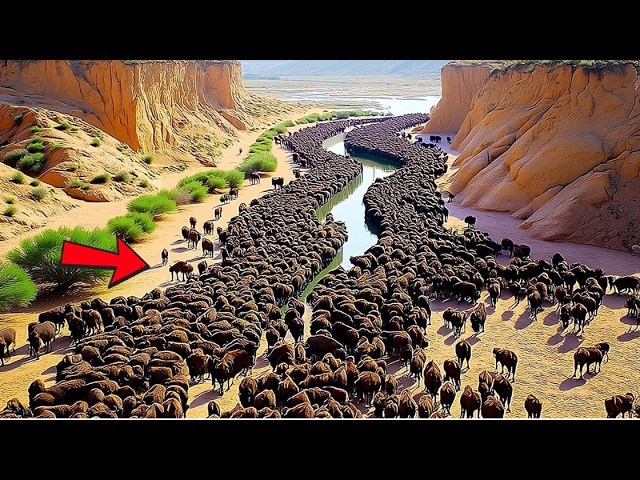

By two thousand eighteen, the original herd had grown to more than two hundred animals.

Native grasses once thought locally extinct reappeared.

Seasonal wetlands formed in bison wallows, supporting amphibians and pollinators.

Small streams flowed longer after rainfall.

Aerial imagery confirmed a visible shift from brown to green across large areas.

Local communities noticed changes as well.

Improved soil moisture benefited nearby agriculture.

Wildlife sightings increased.

The return of bison also carried cultural meaning for Indigenous descendants, reconnecting history, land, and identity.

The success in Mexico mirrored other restoration efforts worldwide.

In Yellowstone National Park, the reintroduction of wolves reshaped river systems by altering herbivore behavior.

In Africa and Asia, elephants maintained savannas and forests through their movement and feeding patterns.

These examples shared a common lesson.

Removing keystone species destabilizes ecosystems.

Restoring them can initiate recovery without intensive human control.

The bison did not heal the land intentionally.

They followed instinct shaped by evolution.

Their daily routines accomplished what machinery and funding had failed to achieve.

The experiment demonstrated that ecological repair often requires humility rather than dominance.

Challenges remain.

Climate change continues to pressure dry regions.

Land use conflicts persist.

Protection from po*ching and habitat fragmentation is ongoing.

Yet the transformation achieved within ten years offers a blueprint.

Restoration does not always require invention.

Sometimes it requires remembering what was lost.

The return of bison to Mexico transformed a landscape many had written off as beyond saving.

It proved that even severely degraded land retains memory and potential.

When the right species return, natural processes resume.

Soil breathes.

Water stays.

Life follows.

The story stands as evidence that renewal is possible when ecosystems are allowed to function as they once did.

In a world facing widespread environmental decline, the lesson from the Mexican plains is clear.

Sometimes the most effective solution is to step back, restore what belongs, and let nature do the rest.

News

R. Kelly’s Attorney Files Motion for Immediate Release

A new and highly unusual legal filing has brought renewed attention to the case of R Kelly, the once…

Reshona Landfair on her life after R Kelly: ‘I had to rebuild my entire self’

Former ‘Jane Doe’ Speaks Out: Reclaiming Identity After R Kelly Abuse On February 5, 2026, Reshona Landfair, previously known only…

Former ‘Jane Doe’ Speaks Out and Reclaims Her Identity After R. Kelly Ab se

Former ‘Jane Doe’ Speaks Out: Reclaiming Identity After R Kelly Abuse On February 5, 2026, Reshona Landfair, previously known only…

50 Cent’s New Documentary Part 2 Reveals What Was Hidden About Diddy & Jay Z What If the Second Installment Finally Connects Dots the Industry Spent Years Avoiding? Fresh narration, resurfaced footage, and pointed commentary revisit long-whispered stories surrounding influence, alliances, and power behind the scenes. The timing, framing, and implications are reigniting debate—what’s shown, what’s implied, and why it matters now unfolds when you follow the article link in the comment.

For more than two decades, tension between two of hip hop’s most powerful figures has existed not as open conflict,…

Excavators Just Opened a Sealed Chamber Under Temple Mount — And One Detail Still Terrifies Experts

For centuries, the Temple Mount in Jerusalem has stood as one of the most sensitive and symbolically powerful locations on…

50 Cent’s New Documentary Part 2 Reveals What Was Hidden About Diddy & Jay Z

The long and complicated rivalry between two of the most powerful figures in modern hip hop has resurfaced with renewed…

End of content

No more pages to load