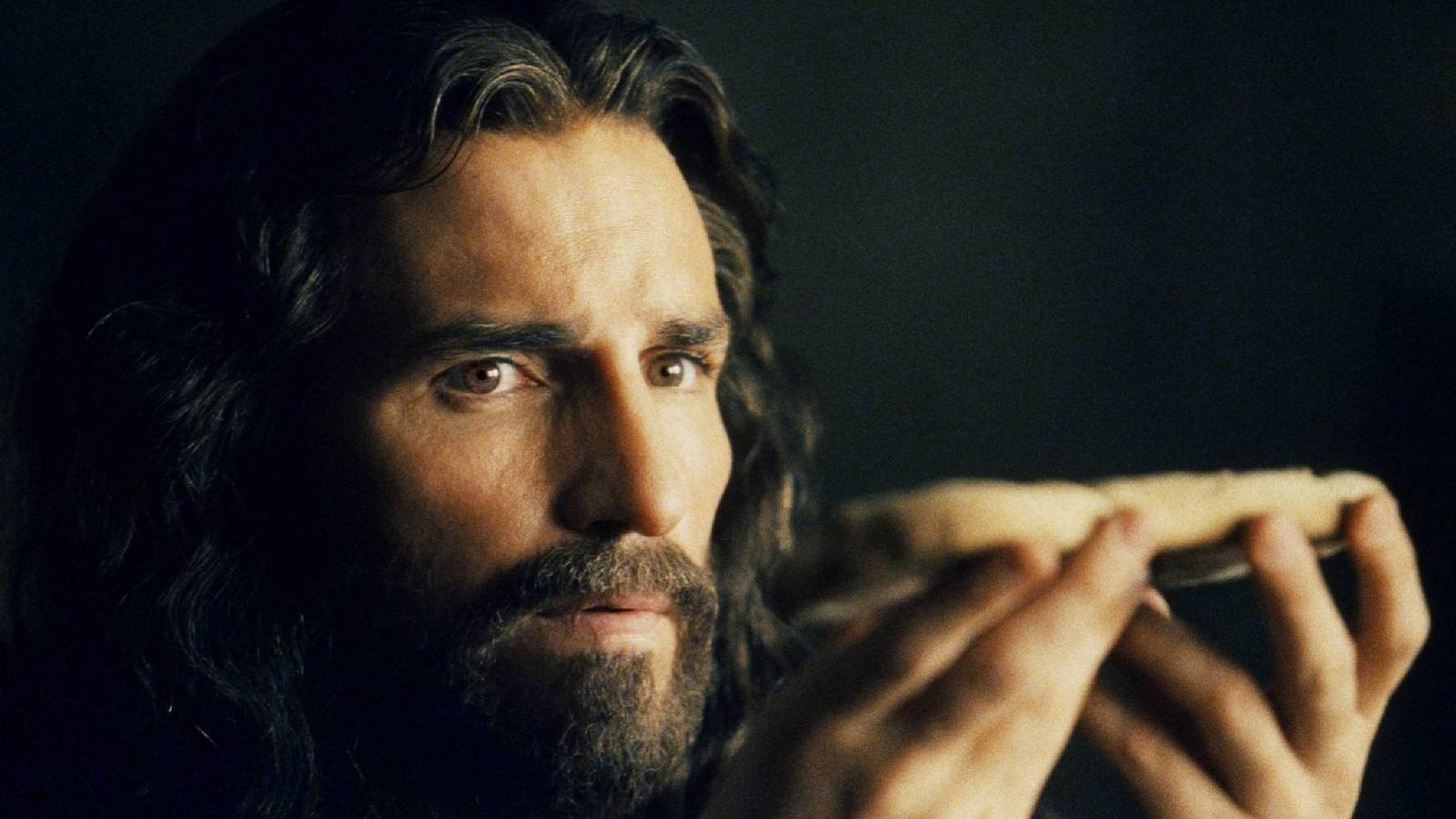

Mel Gibson’s Ambitious Return to Sacred Cinema: Inside the Vision for “The Resurrection of the Christ”

More than two decades after “The Passion of the Christ” became one of the most controversial and financially successful religious films in history, director Mel Gibson is preparing to return to the story that defined a major chapter of his career.

In a wide ranging interview, Gibson offered rare insight into his plans for an ambitious new project tentatively titled “The Resurrection of the Christ,” a film he describes as his most complex, risky, and spiritually demanding undertaking to date.

The project, still in early development, is intended to explore the events following the crucifixion of Jesus, extending far beyond the familiar three days between death and resurrection.

According to Gibson, the narrative will span realms rarely depicted in mainstream cinema, from the fall of the angels to the descent into hell, and eventually to the death of the last apostle.

It is a scope that reaches far beyond traditional biblical epics, and one that Gibson admits may be the most difficult challenge of his career.

Central to the discussion is the question that has lingered since the original film’s release in 2004: who will portray Jesus.

Gibson confirmed that Jim Caviezel, who played Christ in “The Passion of the Christ,” remains his intended choice, despite the fact that more than twenty years have passed since the first production.

The chronological contradiction is obvious.

The story is meant to take place only days after the crucifixion, yet the actor is now two decades older.

Gibson acknowledged the challenge openly.

He said that modern visual effects would allow filmmakers to overcome the problem in ways that were not possible in the past.

Advances in digital technology, particularly in facial de aging and motion capture, now make it feasible to recreate the appearance of actors at earlier stages of their lives.

He expressed confidence that by the time filming begins, these tools will be even more refined, allowing continuity between the two films while preserving the emotional authenticity of the performance.

The director suggested that several performers from the original production could return in their previous roles, aided by these same techniques.

He described contemporary computer generated imagery as capable of “amazing things,” noting that audiences now routinely accept transformations that once would have seemed implausible or distracting.

For Gibson, technology is not merely a technical solution but an artistic instrument that allows him to preserve the spiritual continuity of the story.

Despite the enthusiasm, Gibson emphasized that the project remains in a delicate stage.

He does not yet have a firm production schedule and expects pre production to take considerable time.

He said the film would begin “next year sometime” at the earliest, but stressed that the process must unfold at its own pace.

The script, he explained, took years to complete and required extraordinary collaboration.

Gibson wrote the screenplay with his brother and longtime collaborator Randall Wallace.

He described the writing process as intense and unconventional, calling the finished script unlike anything he had ever read.

He characterized the narrative as “an acid trip,” a phrase that underscored the surreal and metaphysical elements he intends to explore.

The story, he said, moves across spiritual realms, confronting themes of rebellion, redemption, judgment, and cosmic order.

The structure begins not with the resurrection itself, but with the fall of the angels.

In Gibson’s conception, the story must establish the origin of evil before depicting its defeat.

That requires venturing into abstract territory rarely attempted in religious cinema.

He spoke of depicting other realms, descending into hell, and introducing figures such as Satan with an origin story that carries theological weight.

Representing such concepts on screen presents both artistic and spiritual difficulties.

Gibson said he has spent years thinking about how to evoke emotions through imagery rather than relying on obvious or sensational techniques.

He hopes to avoid visual clichés and instead create an experience that feels mysterious, unsettling, and profound.

The challenge, he explained, lies in presenting the invisible world in a way that resonates with human psychology and spiritual intuition.

The director admitted candidly that he is not entirely certain he can achieve what he envisions.

He described the film as “super ambitious” and acknowledged that its scope might exceed the practical limits of filmmaking.

Yet he expressed a willingness to take the risk, arguing that creative endeavors of spiritual significance require courage and uncertainty.

For Gibson, the effort itself carries meaning, regardless of the outcome.

Consultation plays a central role in the project.

Gibson confirmed that he works closely with biblical scholars, theologians, and historians to ensure that the narrative remains grounded in scripture and tradition.

He described repeatedly reading the Bible and discovering connections between passages that emerge only through prolonged study.

These correlations, he said, shape the architecture of the story and determine how events are positioned within the larger theological framework.

He emphasized that interpretation is unavoidable.

The resurrection narrative is not fully detailed in scripture, leaving gaps that must be approached with reverence and intellectual honesty.

Gibson said the task requires balancing fidelity to doctrine with creative imagination, ensuring that speculative elements “ring true” within the established tradition.

The goal is not novelty, he said, but coherence with the spiritual meaning of the story.

Language presents another major decision.

“The Passion of the Christ” was filmed primarily in Aramaic, Latin, and Hebrew, a choice that distinguished it from nearly all other biblical films.

Gibson is now reconsidering that approach.

While he values the authenticity of ancient languages, he acknowledged that the philosophical and theological complexity of the new project might demand a more accessible vernacular.

He expressed fascination with recent developments in artificial intelligence that allow speech to be translated seamlessly between languages while preserving voice and facial movement.

Such technology, he suggested, could allow the film to be performed in multiple languages without sacrificing emotional continuity.

He remains open to the possibility of beginning in Aramaic, as before, but has not yet reached a final decision.

Gibson recalled that when the original film was released, there were believed to be only about four hundred thousand speakers of Aramaic worldwide.

He took satisfaction in knowing that those audiences could understand the dialogue directly, even as most viewers relied on subtitles.

For the new project, he continues to weigh the symbolic power of ancient language against the practical need for clarity.

Beyond technical considerations, Gibson reflected on the spiritual gravity of the undertaking.

He described the story as requiring precise alignment of events and meanings, arguing that “the position is everything” when dealing with sacred narrative.

The resurrection, he said, cannot be treated as an isolated miracle but must be situated within a cosmic struggle between order and chaos, obedience and rebellion.

He indicated that the film will extend beyond the resurrection itself, tracing the arc of Christian history through the early church and the eventual death of the last apostle.

This expansive timeline reflects Gibson’s belief that the resurrection is not merely an ending, but the beginning of a transformative era that reshaped spiritual history.

Observers note that Gibson’s return to biblical cinema carries symbolic weight.

“The Passion of the Christ” grossed more than six hundred million dollars worldwide and ignited intense debate over violence, theology, and representation.

It also marked a turning point in Gibson’s career, preceding years of personal controversy and professional hiatus.

A sequel, particularly one so ambitious, represents both an artistic resurrection and a personal reckoning.

Industry analysts suggest that the project, if completed, could redefine the modern religious epic.

Advances in visual effects now allow filmmakers to depict metaphysical concepts with unprecedented realism.

At the same time, audiences have grown accustomed to complex mythological universes in popular cinema, creating a cultural environment more receptive to ambitious spiritual narratives.

Yet risks remain substantial.

Theological controversy is likely, particularly regarding depictions of hell, angels, and Satan.

Scholars differ widely on interpretations of these subjects, and any visual representation invites scrutiny.

Financial risks are also significant, given the scale of production and the uncertain commercial appeal of such an abstract narrative.

Gibson appears fully aware of these challenges.

He described the project as taking “its own time,” suggesting that patience may be the most important ingredient.

He dismissed concerns about delay, saying that stories of this magnitude must mature naturally before entering production.

His instincts, he said, tell him that the timing will reveal itself.

Those who have followed Gibson’s career note a consistent pattern: a willingness to confront subjects others avoid, often at great personal and professional cost.

From violent historical epics to spiritual meditations, his films tend to provoke strong reactions.

“The Resurrection of the Christ” seems poised to continue that tradition, offering not comfort but confrontation.

As pre production gradually begins, the film remains shrouded in mystery.

No cast list has been finalized, no filming locations announced, and no release date proposed.

What is clear is that Gibson intends not merely to continue a story, but to reinterpret its cosmic dimensions through cinema.

Whether the project ultimately fulfills its ambition remains uncertain.

Even Gibson admits the possibility of failure.

Yet for a director whose most famous work centered on suffering, sacrifice, and redemption, the attempt itself carries symbolic resonance.

In returning to the resurrection, Gibson is not simply revisiting a narrative, but attempting to explore the boundaries of faith, art, and imagination.

For now, the film exists only as a script, a vision, and a promise.

Its journey to the screen may take years, and its reception may divide audiences as sharply as its predecessor.

But if completed, “The Resurrection of the Christ” may stand as one of the most daring religious films ever attempted, a work that seeks to portray not only a miracle, but the unseen architecture of belief itself.

News

What They Just Pulled From This Sealed Cave in Turkey Has Left Historians Stunned ccv

Archaeological Discoveries in Turkey Recent archaeological excavations in Turkey have led to the remarkable discovery of sealed underground cities and…

3I/ATLAS: ‘1 in a Million Chance’ Interstallar Object is a Natural Comet ccv

The Discovery of 3I/ATLAS: A Unique Interstellar Comet Introduction The recent discovery of the interstellar object 3I/ATLAS has captured the…

Scientists Terrifying New Discovery Of Malaysian Flight 370 Rewrites History ccv

The Mysterious Disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 Introduction The disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 remains one of the…

Here’s Why Mexico Is Extracting Tons of Soil From Gulf of Mexico…

The Remarkable Soil Extraction Project in the Gulf of Mexico Introduction In recent years, Mexico has embarked on an ambitious…

SCIENTIST PANICKED: Camera Captured in Chernobyl So TERRIFYING, They Warned NOT TO ENTER Documentary

The Terrifying Discoveries of Chernobyl: A Cautionary Tale Introduction Chernobyl is a name that resonates with fear and caution. Located…

What Experts Found 8000m Below Puerto Rico Trench, Changes Everything We Know ccv

Groundbreaking Discoveries in the Puerto Rico Trench Introduction Deep within the Atlantic Ocean lies the Puerto Rico Trench, a location…

End of content

No more pages to load