The experience of watching a subtitled film, where the viewer must read while observing images, has long fascinated filmmakers and audiences alike.

It demands attention, comprehension, and a deeper level of engagement.

For director Mel Gibson, that experience became central to one of the most controversial and influential films of modern religious cinema.

He has often reflected that reading text while watching images gives the audience a heightened sense of awareness, almost as if they are participating more actively in the story unfolding before them.

When Gibson first worked with subtitles extensively, the process was challenging.

Over time, however, he developed a fluency that allowed the written word to become a powerful narrative tool rather than a distraction.

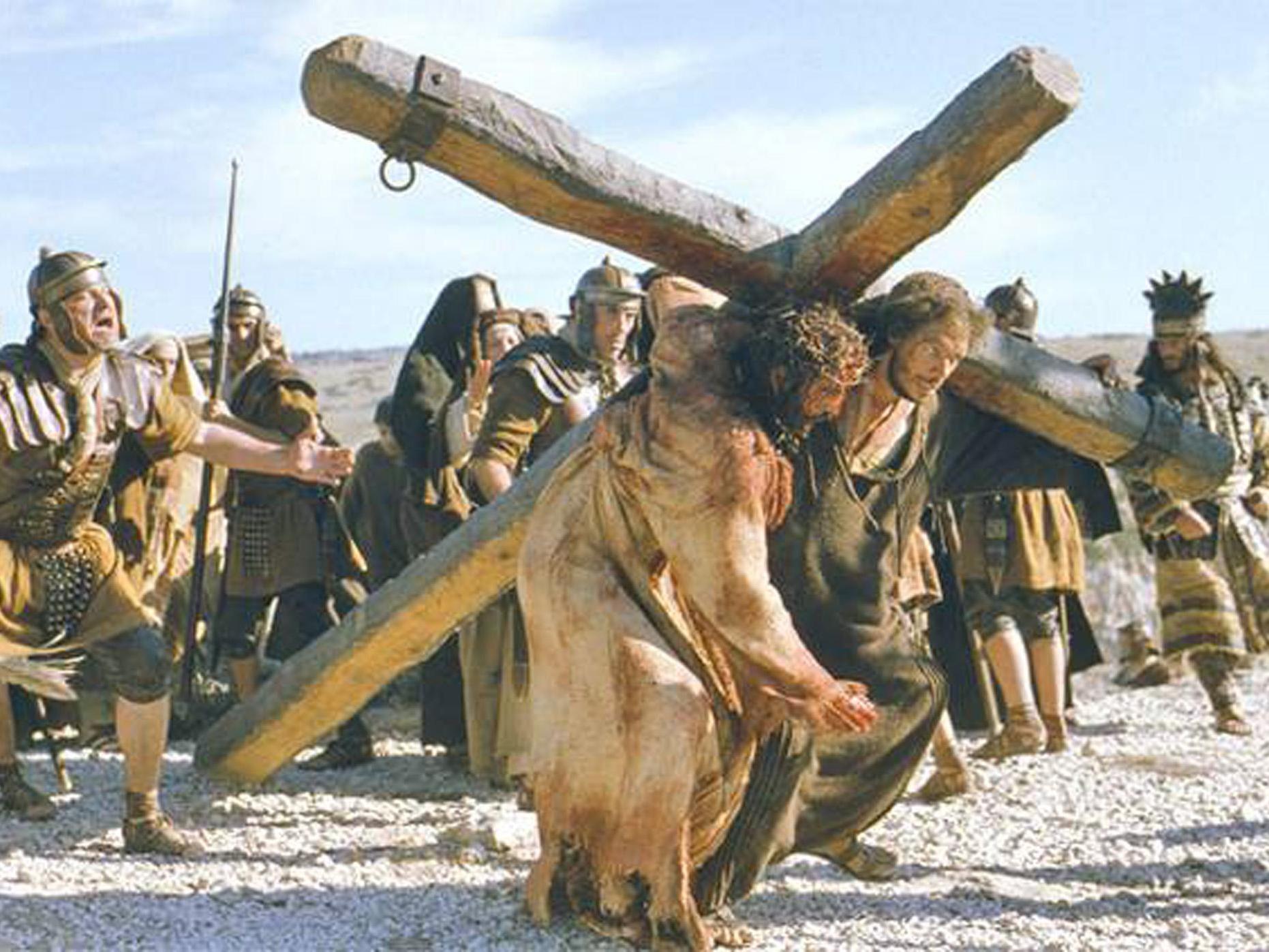

This approach proved especially significant in the making of The Passion of the Christ.

The film relied heavily on ancient languages, and the subtitles carried not only dialogue but centuries of theological weight.

Many viewers, already familiar with the biblical narrative, found that they barely needed to read in order to understand what was happening on screen.

The combination of visual storytelling and sacred text created an unusually intense cinematic experience.

Despite its eventual success, The Passion of the Christ faced considerable resistance, particularly within Hollywood.

Gibson has acknowledged that opposition emerged almost immediately once the subject matter became clear.

While controversy was not unexpected given the scale and significance of the story, the level of hostility surprised many observers.

The film was met with skepticism and, in some circles, outright rejection before it even reached audiences.

The resistance was not merely artistic but cultural.

Within secular Hollywood, Christianity has often occupied a unique position as the one major religion that can be openly criticized without consequence.

Progressive and open minded communities that champion tolerance for many belief systems frequently draw a line when it comes to Christianity, which they associate with historical power structures, colonialism, or social conservatism.

This dynamic created an environment in which a film centered unapologetically on Christian theology was viewed with suspicion.

Gibson’s intention, however, was not political.

His central message was that the crucifixion represented a sacrifice for all humanity.

The suffering depicted on screen was meant to underscore the belief that redemption was offered universally, addressing the fallen nature of humanity rather than condemning it.

For Gibson, this was not an abstract idea but a deeply personal conviction rooted in his upbringing within a Catholic family and his lifelong Christian faith.

Portraying that belief was both an honor and a burden, particularly given the backlash that followed.

Criticism of Christianity, Gibson has noted, is sometimes justified, particularly when institutional failures come to light.

The exposure of clerical abuse scandals and the systemic cover ups that followed have severely damaged the moral authority of the Church.

Figures such as Theodore McCarrick and others became symbols of corruption that contradicted the values Christianity claims to uphold.

These scandals revealed a darker side of the institution, one shaped by power, secrecy, and self preservation.

The Catholic Church, despite its sacred origins, remains a human institution with a long and complex history.

While it was founded on spiritual principles, it has been shaped by flawed individuals and political realities.

Some critics argue that the modern Church has drifted significantly from its original mission.

One prominent voice in this debate is Archbishop Carlo Maria Vigano, who has described the contemporary Church as a counterfeit parallel structure, operating under a different spiritual logic than the one established at its foundation.

This critique is often linked to the changes introduced during the Second Vatican Council in the nineteen sixties.

That council marked a turning point, introducing reforms that altered liturgy, theology, and the Church’s relationship with the modern world.

Prior to that moment, Catholic doctrine had developed with relative internal consistency.

Afterward, many believers perceived a rupture, with new interpretations conflicting with centuries of tradition.

For some, this shift represented adaptation.

For others, it signaled abandonment.

Concerns about legitimacy extend even further back.

The election of Pope John the Twenty Third in nineteen fifty eight has been the subject of lingering speculation.

During that conclave, white smoke was reportedly seen before black smoke followed, an unprecedented sequence in papal history.

White smoke traditionally signals the successful election of a pope, while black smoke indicates failure to reach consensus.

The appearance of both led some to question whether internal power struggles influenced the outcome.

John the Twenty Third also took a papal name previously associated with an antipope from the fifteenth century.

That historical figure had later admitted his illegitimacy and sought reconciliation with the Church.

The choice of the same name raised eyebrows among those attentive to symbolic continuity and historical precedent.

While the Church has endured periods of corruption before, including during the reigns of notorious popes, such moments continue to fuel skepticism about institutional authority.

The Vatican itself embodies this tension between spiritual mission and worldly power.

It is a sovereign state enclosed within the city of Rome, protected by walls and exempt from many external legal processes.

The immense wealth represented by its art and architecture stands in stark contrast to the poverty preached in the Gospels.

This concentration of power has occasionally provided refuge for individuals seeking to evade accountability, reinforcing perceptions of moral inconsistency.

Allegations surrounding the relocation of abusive clergy have been among the most damaging.

In some cases, priests accused of harming children were moved to new locations where they continued to offend.

Such actions are widely regarded as among the gravest moral failures of the modern Church.

While similar abuses have occurred in other institutions, the betrayal feels particularly severe given the Church’s claim to moral leadership.

Critics argue that these failures are symptoms of deeper corruption that developed over centuries.

From this perspective, the crisis is not merely about individual wrongdoing but about a system that prioritizes its own survival over justice.

Vatican Two, according to its detractors, accelerated this decline by introducing ambiguity where clarity once existed.

Recent controversies have intensified these concerns.

Actions interpreted as religious syncretism, such as the presence of indigenous religious symbols within Vatican ceremonies, have been viewed by some as a departure from core Christian doctrine.

The appearance of the Pachamama figure during events associated with the Amazon Synod sparked outrage among traditionalists, who regarded it as a violation of the commandment against worshiping false gods.

Such actions have been described as apostasy, a deliberate turning away from established belief.

Apostasy, by definition, occurs from within, requiring prior belonging.

This has led some observers to describe the crisis within the Church as an internal struggle rather than an external attack.

From this viewpoint, the conflict reflects a broader spiritual battle rather than a purely institutional dispute.

Gibson has suggested that this struggle mirrors a larger cosmic conflict between good and evil.

In his understanding, humanity occupies a central role in this conflict, despite its flaws and apparent insignificance.

Institutions that claim to mediate the divine are inevitably drawn into this struggle, sometimes losing ground not through malice but through weakness.

These themes form the foundation of Gibson’s long anticipated sequel to The Passion of the Christ, focused on the Resurrection.

Unlike the crucifixion, which unfolds within a linear historical framework, the Resurrection presents unique narrative challenges.

It transcends ordinary experience and requires a broader conceptual context.

To address this, Gibson and his collaborators spent six to seven years developing a script that situates the Resurrection within a larger spiritual and historical framework.

The project involved extensive research.

Gibson regards the Gospels as verifiable historical documents, supported by external accounts from the same period.

He points to the willingness of the apostles to die rather than deny their testimony as evidence of sincerity.

From his perspective, no one willingly dies for what they know to be false.

The Resurrection remains the most challenging aspect of Christian belief for many.

It demands faith beyond ordinary historical reasoning.

The idea that a man publicly executed could rise again after three days under his own power has no parallel in other religious traditions.

Gibson maintains that this event is the cornerstone of Christian belief and the ultimate test of faith.

His conviction developed over time.

As a child, he accepted these beliefs through trust in his parents and upbringing.

His father, known for exceptional intellectual ability, influenced his respect for disciplined thinking.

As an adult, Gibson’s faith was reinforced through study, historical analysis, and personal experience.

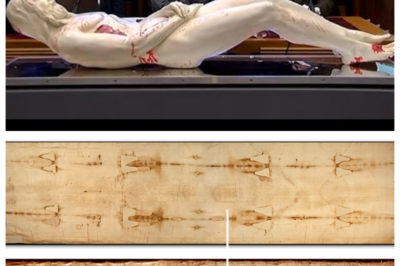

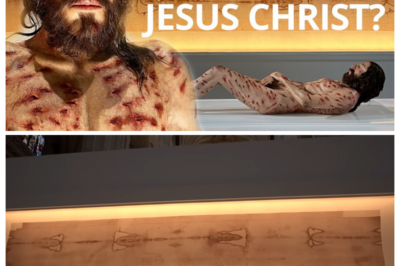

One such experience involves the Shroud of Turin.

Once believed to date from the medieval period, more recent analysis has suggested a much older origin.

The image on the cloth remains unexplained, with no evidence of paint or known artistic technique.

Some scientists have proposed that an intense burst of energy may have produced a photographic like imprint, a phenomenon not achievable with ancient technology.

For Gibson, such mysteries reinforce rather than replace faith.

They suggest that reality may be more complex than current understanding allows.

As debate continues, these questions remain at the intersection of science, history, and belief.

In the end, the discussion surrounding faith, institutions, and power reflects a deeper human struggle.

It asks whether spiritual truth can survive within structures shaped by politics and ambition.

For Gibson and others who share his concerns, the answer lies not in abandoning belief but in returning to its foundations.

News

JRE: “Scientists Found a 2000 Year Old Letter from Jesus, Its Message Shocked Everyone”

There’s going to be a certain percentage of people right now that have their hackles up because someone might be…

If Only They Know Why The Baby Was Taken By The Mermaid

Long ago, in a peaceful region where land and water shaped the fate of all living beings, the village of…

If Only They Knew Why The Dog Kept Barking At The Coffin

Mingo was a quiet rural town known for its simple beauty and close community ties. Mud brick houses stood in…

What The COPS Found In Tupac’s Garage After His Death SHOCKED Everyone

Nearly three decades after the death of hip hop icon Tupac Shakur, investigators searching a residential property connected to the…

Shroud of Turin Used to Create 3D Copy of Jesus

In early 2018 a group of researchers in Rome presented a striking three dimensional carbon based replica that aimed to…

Is this the image of Jesus Christ? The Shroud of Turin brought to life

**The Shroud of Turin: Unveiling the Mystery at the Cathedral of Salamanca** For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has captivated…

End of content

No more pages to load