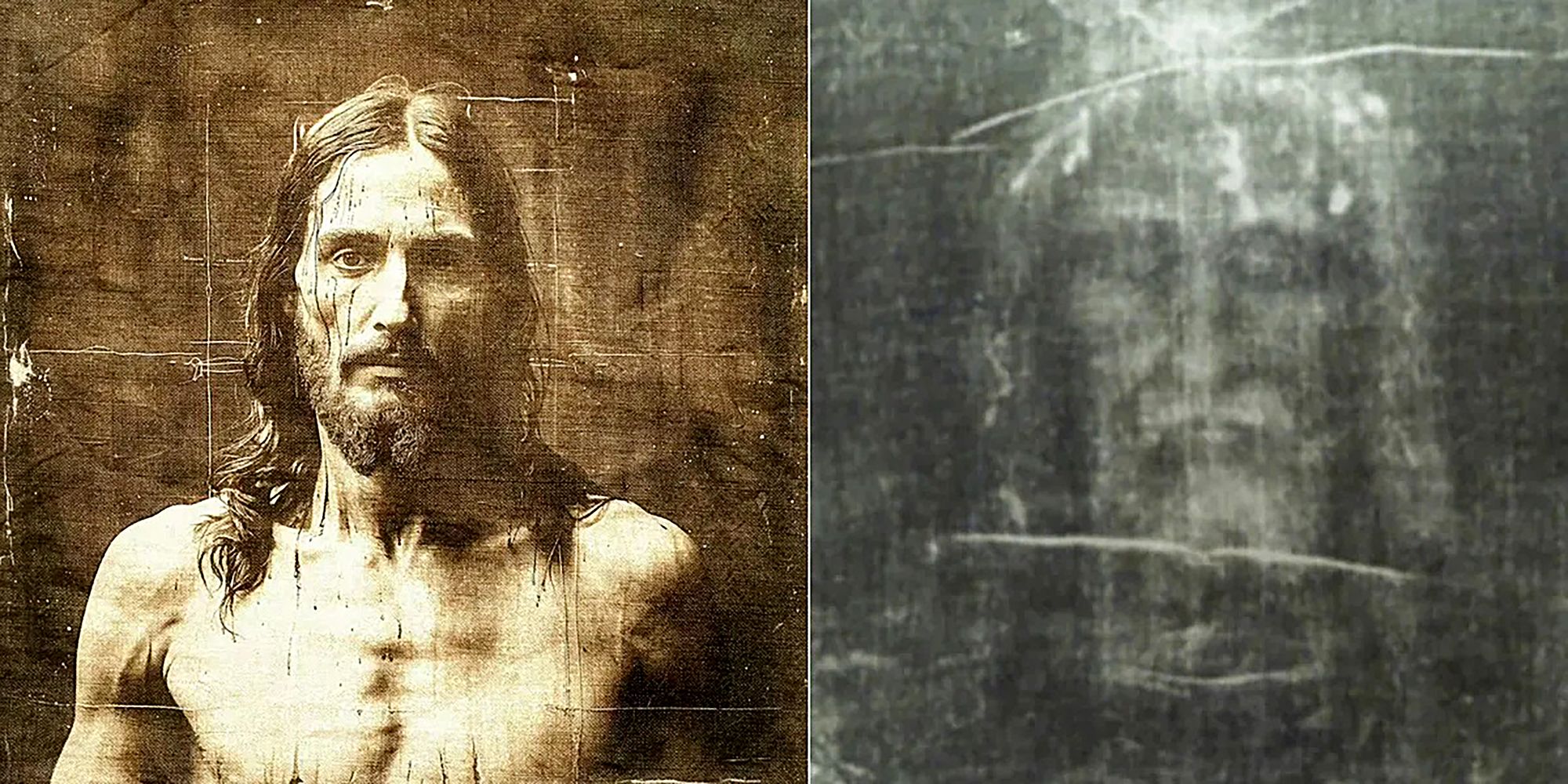

For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has stood at the intersection of faith, history, and science.

It is a linen cloth bearing the faint yet haunting image of a crucified man, marked with wounds that correspond with striking precision to the known methods of Roman execution.

The image depicts a body scourged, pierced, crowned with thorns, and nailed in a manner consistent with first century crucifixion practices.

For believers, the cloth represents the burial shroud of Jesus of Nazareth.

For skeptics, it has long been dismissed as a medieval artifact.

Yet modern scientific inquiry has steadily reopened a debate once thought settled.

The Shroud is unique among historical objects.

It is not merely an image but a negative image, one that reveals greater clarity when photographed.

It is not painted, dyed, or drawn.

The coloration exists only on the outermost surface of the linen fibers, penetrating no more than a few microns deep.

This superficiality has become one of its greatest mysteries, as no known artistic or chemical process has successfully replicated the effect.

Over the past five decades, the Shroud has been subjected to intense scrutiny by scientists from more than one hundred academic disciplines.

Physicists, chemists, textile experts, forensic pathologists, medical doctors, archaeologists, and engineers have devoted hundreds of thousands of research hours to its analysis.

Despite this unprecedented level of examination, no consensus explanation has emerged for how the image was formed.

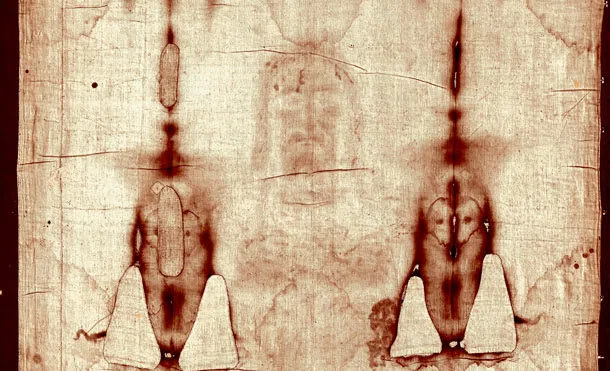

The figure on the cloth exhibits wounds that align closely with Gospel descriptions of Jesus’s execution.

The wrists show puncture wounds consistent with nails driven through the radius bones rather than the palms, a detail unknown to medieval artists but required to support a body’s weight.

The feet bear a single nail wound.

The back is covered with hundreds of dumbbell shaped marks matching Roman flagrum scourges.

The scalp shows blood patterns consistent with a cap of thorns rather than a single circlet.

A large wound on the right side of the chest matches a postmortem spear thrust that pierced the lung cavity, producing a flow of blood and clear fluid.

Forensic analysis has determined that the blood on the Shroud is real human blood, specifically type AB.

The blood was deposited before the image was formed, meaning the image did not create the bloodstains.

This sequencing is significant, as it eliminates many artistic explanations.

The blood also contains evidence of pulmonary edema, a fluid associated with asphyxiation, consistent with death by crucifixion.

One of the most puzzling characteristics of the Shroud is that its image disappears when viewed too closely.

At distances under several feet, the image fragments into individual fibers, losing all recognizable form.

Only at a distance does the full image resolve.

This optical behavior has no parallel in known artworks and continues to challenge reproduction efforts.

Scientific teams such as the Shroud of Turin Research Project concluded after extensive testing that the image is not the result of pigment, paint, dye, scorching, or photography.

No brush strokes, binding agents, or artistic residues were found.

The image is chemically distinct from the bloodstains and exists only as a surface oxidation of the linen fibers.

One of the most controversial moments in the Shroud’s modern history occurred in 1988, when radiocarbon testing dated a small sample of the cloth to the medieval period.

For many, this result appeared to close the case.

However, serious questions soon emerged regarding the sampling process, contamination, and statistical handling of the data.

The tested fragment was taken from a corner of the cloth that had undergone documented repairs following a sixteenth century fire.

Subsequent analysis suggested the presence of foreign fibers and potential bioplastic contamination, both of which could significantly distort radiocarbon results.

In recent years, alternative dating methods have produced results consistent with much greater antiquity.

Wide angle X ray scattering analysis conducted by Italian researchers compared the natural aging of linen fibers on the Shroud with linen samples from first century burial contexts.

The results indicated a degradation timeline compatible with approximately two thousand years of aging rather than several hundred.

Additional chemical evidence supports this conclusion.

The absence of vanillin, a natural component of lignin in flax fibers, suggests an age far older than the medieval period.

Linen textiles of known age demonstrate that vanillin content decreases slowly over millennia, and its complete absence on the Shroud aligns with ancient rather than medieval linen.

Beyond the Shroud itself, a second artifact has become increasingly relevant to the discussion.

Known as the Sudarium of Oviedo, this cloth is believed to be the head covering mentioned in the Gospel of John.

Unlike the Shroud, the Sudarium does not bear an image but is heavily stained with blood.

Historical records place it securely in Spain by the early medieval period, with documentation tracing it back to the sixth century.

What makes the Sudarium significant is its forensic correspondence with the Shroud.

Bloodstain patterns on the Sudarium match the facial wounds seen on the Shroud with remarkable precision.

When overlaid, the dimensions, orientation, and injury locations align exactly.

Both cloths share the same rare AB blood type and the same blood chemistry, including pulmonary edema fluid.

These correlations strongly suggest that both cloths covered the same individual at different stages following death.

The Sudarium also contains pollen grains from regions consistent with a journey from Jerusalem through North Africa and into Spain.

Similar pollen signatures have been identified on the Shroud.

Some of these pollen species bloom only in the area around Jerusalem during the spring, aligning with the Passover season described in the Gospel accounts.

Microscopic analysis has further revealed traces of limestone dust embedded in the Shroud’s fibers.

The mineral composition matches limestone found in the Jerusalem region, particularly near known first century burial sites.

Concentrations of this dust appear on the knees, feet, and nose of the figure, consistent with a man who fell face forward while carrying a heavy object.

Historical archaeology reinforces this context.

Roman crucifixion is among the best attested practices of the ancient world, described by multiple independent sources including Roman historians.

The execution of Jesus of Nazareth under the authority of Pontius Pilate is documented not only in Christian texts but also in non Christian sources such as Tacitus.

Coins and material artifacts from the period further anchor the narrative in history.

Temple tax coins minted in Tyre during the governorship of Pontius Pilate are consistent with Gospel references to Passover practices in Jerusalem.

These coins were required for worship and circulated widely in Judea at the time.

Archaeological evidence also confirms the location traditionally identified as the site of Jesus’s burial.

The Church of the Holy Sepulcher stands over a first century limestone quarry containing tombs consistent with the burial practices of wealthy Jews.

Roman efforts to suppress Jewish and early Christian worship inadvertently preserved the site by constructing pagan temples over it, marking the location for later rediscovery.

For many scholars, the Shroud represents an extraordinary convergence of evidence.

It brings together death, burial, and a moment that defies conventional explanation.

While science cannot affirm resurrection, it has been unable to identify any natural mechanism capable of producing the Shroud’s image.

The hypothesis that the image resulted from a burst of radiant energy remains speculative, yet it is one of the few models consistent with the data.

The enduring power of the Shroud lies not only in its mystery but in its humanity.

It presents not an abstract symbol but the battered body of a real man who suffered intensely.

Whether approached as an object of faith or of inquiry, the cloth confronts observers with a stark reality of suffering and sacrifice.

In an age marked by skepticism and digital abstraction, the Shroud of Turin remains a tangible challenge.

It resists easy dismissal and simplistic explanations.

It demands careful thought, rigorous study, and intellectual humility.

For believers, it is a silent testimony to love and redemption.

For historians and scientists, it is one of the most complex artifacts ever studied.

Two thousand years after the crucifixion it appears to depict, the Shroud continues to provoke questions that no generation has fully answered.

Its image endures, faint yet indelible, inviting the modern world to look, examine, and decide what it truly sees.

News

5 Minutes Ago! Pope Leo XIV makes UNEXPECTED decision about ROBERT SARAH and SHOCKS the Vatican!

Just before dawn, a quiet decision taken within the Vatican began to ripple outward, unsettling assumptions and reshaping expectations long…

Pope Leo XIV Declares The Antichrist Has Already Spoken From Within the Holy City A statement attributed to Pope Leo XIV has ignited intense debate after reports claimed he warned that a deceptive voice had already emerged from within the Holy City itself. Was this meant as a literal declaration, a symbolic warning, or a theological reflection on MORAL DECEPTION and SPIRITUAL AUTHORITY in the modern era? As theologians analyze the language and believers debate its meaning, questions are growing about PROPHECY, INTERPRETATION, and WHY SUCH WORDS WOULD BE SPOKEN NOW.

With official clarification limited and reactions spreading rapidly, the message has become one of the most unsettling and controversial discussions facing the Church in recent memory.

In the quiet hours before dawn on January third, inside a chapel where no cameras waited and no announcements had…

Elon Musk: “Grok AI Was Asked About Jesus, The Answer It’s Worse Than We Thought!

The release of Grock 4 by Elon Musk company xAI has sparked intense discussion across both the technology and religious…

SCIENTIST STUNNED: Camera Captured in Chernobyl So TERRIFYING, They Warned NOT TO ENTER | Documentary Researchers reviewing footage captured inside the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone reportedly halted further access after a camera recorded something deeply unsettling—prompting warnings against entering the area without strict controls. What did the footage actually show, why did it alarm seasoned scientists, and could the explanation lie in RADIATION EFFECTS, STRUCTURAL DECAY, or MISINTERPRETED VISUAL DATA? As experts analyze the environment’s extreme conditions and the limits of human perception, the incident raises questions about HIDDEN DANGERS that still linger decades after the disaster.

With details released cautiously, the footage has reignited debate over what remains unseen—and unsafe—inside Chernobyl.

👉 Click the Article Link in the Comments to Examine the Footage—and the Science Behind the Warning.

It is now widely accepted that the Soviet Union suffered one of the most severe nuclear disasters in human history…

Governor Of California SCRAMBLES As Lawsuit SHUT DOWN Refinery In California

Eight days ago, California experienced one of the most consequential energy infrastructure failures in its modern history. The permanent shutdown…

3 MIN AGO: ICE & FBI STORM M1nneap0l1s — $4.7 M1ll10n, 23 C0ca1ne Br1cks & S0mal1 Senat0r EXPOSED

In the early h0urs 0f a fr0zen M1nneap0l1s m0rn1ng, the qu1et streets 0f the Cedar R1vers1de ne1ghb0rh00d b0re w1tness t0…

End of content

No more pages to load