For thousands of years, ancient Egyptian mummies have stood as silent witnesses to one of the most death-focused civilizations in human history.

Wrapped in layers of linen, sealed inside coffins, and hidden deep within tombs, these bodies were never meant to be disturbed.

To the Egyptians, opening a mummy was unthinkable.

The body was not merely a shell but an anchor for the soul, essential for survival beyond death.

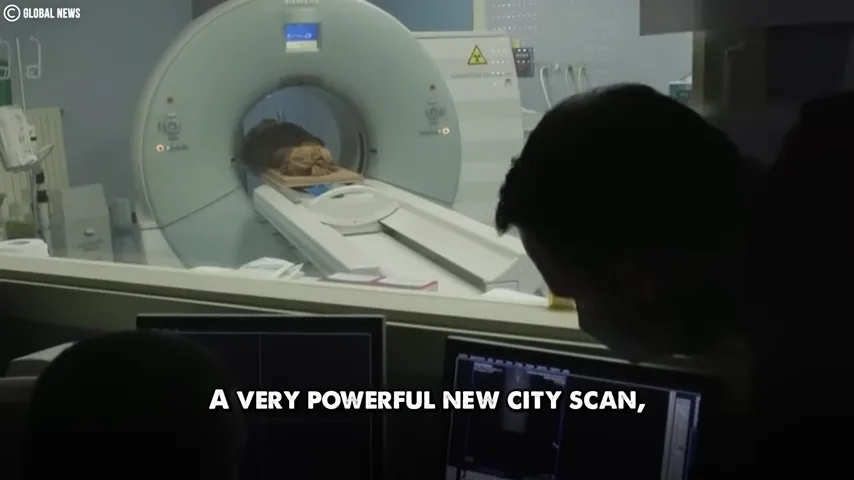

Yet today, without cutting a single bandage, scientists are looking inside these ancient remains—and what they are discovering is reshaping everything we thought we knew about ancient Egypt.

The revolution has come not from shovels or chisels, but from technology.

Advanced CT scanning, combined with artificial intelligence and digital reconstruction, now allows researchers to “virtually unwrap” mummies layer by layer.

These scans reveal bones, organs, amulets, resins, and even diseases in astonishing detail, all while leaving the physical body untouched.

What emerges is not just a picture of how Egyptians prepared their dead, but a far more intimate story about belief, fear, status, and the human experience itself.

Ancient Egypt is often described as obsessed with death, but this perception exists largely because death is what survived.

Daily life—homes, clothing, tools, meals—has mostly vanished.

What remains are tombs, coffins, inscriptions, and preserved bodies.

These remnants show that preparing for death was not a marginal activity.

It was a central duty, shaped by the belief that death marked the beginning of a dangerous and uncertain journey rather than the end of existence.

According to Egyptian belief, the soul depended on the body.

If the body decayed or was destroyed, the soul would be lost forever.

Preservation was therefore an act of survival.

Mummification was designed to keep the body recognizable, intact, and protected for eternity.

Modern CT scans now allow scientists to see exactly how carefully this was done.

One of the most striking revelations from scanning technology is the precision of mummification practices.

Internal organs that decay quickly—the lungs, liver, stomach, and intestines—were removed through a small incision and preserved separately.

CT imaging shows how the empty body cavity was then treated with resins and linen to maintain shape and prevent collapse.

The brain, considered unimportant to thought or identity, was extracted through the nose, leaving behind a hole at the base of the skull that is still clearly visible in scans today.

Hardened resin lining the skull confirms this process beyond any doubt.

The heart, however, was treated very differently.

It was left inside the chest.

In Egyptian belief, the heart was the center of intelligence, emotion, and moral character.

It would be weighed in the afterlife during judgment.

Without it, the soul could not be declared worthy.

CT scans consistently confirm the presence of the heart in properly prepared mummies, offering physical proof of deeply held religious ideas.

Perhaps even more unsettling are the objects hidden within the wrappings.

CT images reveal dozens of amulets placed at precise locations across the body—over the chest, along the spine, between layers of linen.

These were not decorative items.

Each amulet had a specific protective role, guarding against supernatural threats or reinforcing vulnerable parts of the body.

Their careful placement shows that mummification followed strict ritual rules, not improvisation.

In some cases, scans have uncovered extraordinary surprises.

One of the most remarkable involved a woman known as the “Mysterious Lady,” who died around two thousand years ago.

CT imaging revealed that she was pregnant at the time of death—and that the fetus had been preserved inside her womb.

This discovery was unprecedented.

Chemical conditions created by embalming and natural salts preserved both mother and child for millennia, something no one could have known without modern imaging.

CT scans have also exposed evidence of disease and trauma that changes how we view ancient lives.

Signs of cancer, infections, malnutrition, bone deformities, and healed fractures appear frequently.

These findings remind us that mummies are not symbols; they are individuals who lived with pain, illness, and physical limitations.

In some cases, scans show injuries that suggest accidents or violence, offering clues about how people died and how dangerous life could be.

The most famous example of this technological transformation is the mummy of Tutankhamun.

When his tomb was discovered in 1922, it dazzled the world with gold and treasure.

Yet it was modern CT scanning that revealed the darker story hidden beneath the wrappings.

The scans showed fragile bones, genetic disorders caused by close family intermarriage, evidence of malaria, and a severe leg injury that may have contributed to his death.

Even more disturbing was evidence that parts of his body had burned after burial, caused by a chemical reaction between embalming oils and resins.

This accidental combustion occurred while the body was sealed inside the coffin, adding a tragic and unexpected layer to the young king’s story.

Beyond royal mummies, CT technology has shifted attention toward ordinary people.

Priests, officials, artisans, and workers—once known only through inscriptions—are now studied as biological individuals.

By analyzing bone structure, dental wear, and joint damage, scientists can infer diet, labor, and lifestyle.

Mummies have become biological archives, preserving evidence of daily life as clearly as any written record.

Artificial intelligence has amplified these discoveries.

Machine-learning systems are now used to reconstruct damaged inscriptions, identify patterns in burial practices, and even estimate age and sex more accurately.

In tombs damaged by flooding or time, AI-assisted imaging allows scholars to rebuild wall texts and decorative programs that are invisible to the naked eye.

This combination of ancient remains and modern algorithms has created a new era in archaeology—one where destruction is replaced by digital preservation.

These tools have also played a critical role in recent discoveries, such as the identification of lost royal tombs and mass burials.

In Saqqara, dozens of perfectly preserved sarcophagi belonging to priests and officials were discovered sealed for more than two millennia.

CT scans revealed intact mummies, vivid coffin paintings, and complex burial equipment, demonstrating that elite religious figures were buried with care rivaling that of royalty.

Elsewhere, scanning has revealed darker aspects of Egyptian ritual life.

Mummified animals—especially crocodiles sacred to the god Sobek—have been found in mass graves.

CT imaging shows that some were not embalmed traditionally but were bound and left to die, likely as ritual offerings.

In other sites, severed hands from defeated enemies have been discovered, arranged ceremonially, revealing how violence and religion sometimes intersected with power.

Perhaps most striking is how these discoveries reshape the idea that Egypt was merely obsessed with death.

What emerges instead is a civilization intensely focused on continuity.

Preservation, ritual, and judgment were not about glorifying death but about ensuring survival beyond it.

Life, morality, and social order were believed to echo eternally.

Modern technology has made these beliefs visible again.

CT scans do not just reveal bones and objects; they reveal intent.

Every incision, every amulet, every preserved organ reflects fear, hope, and faith.

The ancient Egyptians invested extraordinary effort into preparing for a future they believed was real and immediate.

As scanning technology continues to advance, the potential for discovery grows.

Hidden diseases, unknown rituals, and unexamined individuals still rest within museum collections and sealed tombs.

Each scan adds detail to a story that is far from complete.

Without opening a single tomb, science is uncovering truths that have slept for thousands of years.

The mummies of ancient Egypt, once thought fully understood, are speaking again—through data, images, and digital reconstructions.

What they reveal is not only terrifying or astonishing, but deeply human: a civilization confronting mortality with preparation, belief, and remarkable care.

And as technology continues to peer beneath the linen and resin, one truth becomes clear—ancient Egypt still has secrets to tell, and modern science has only just begun to listen.

News

Black CEO Denied First Class Seat – 30 Minutes Later, He Fires the Flight Crew

You don’t belong in first class. Nicole snapped, ripping a perfectly valid boarding pass straight down the middle like it…

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 7 Minutes Later, He Fired the Entire Branch Staff

You think someone like you has a million dollars just sitting in an account here? Prove it or get out….

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 10 Minutes Later, She Fires the Entire Branch Team ff

You need to leave. This lounge is for real clients. Lisa Newman didn’t even blink when she said it. Her…

Black Boy Kicked Out of First Class — 15 Minutes Later, His CEO Dad Arrived, Everything Changed

Get out of that seat now. You’re making the other passengers uncomfortable. The words rang out loud and clear, echoing…

She Walks 20 miles To Work Everyday Until Her Billionaire Boss Followed Her

The Unseen Journey: A Woman’s 20-Mile Walk to Work That Changed a Billionaire’s Life In a world often defined by…

UNDERCOVER BILLIONAIRE ORDERS COFFEE sa

In the fast-paced world of business, where wealth and power often dictate the rules, stories of unexpected humility and courage…

End of content

No more pages to load