The Shroud of Turin is one of the most mysterious and controversial religious artifacts in human history.

For centuries it has inspired devotion, skepticism, scientific investigation, and philosophical debate.

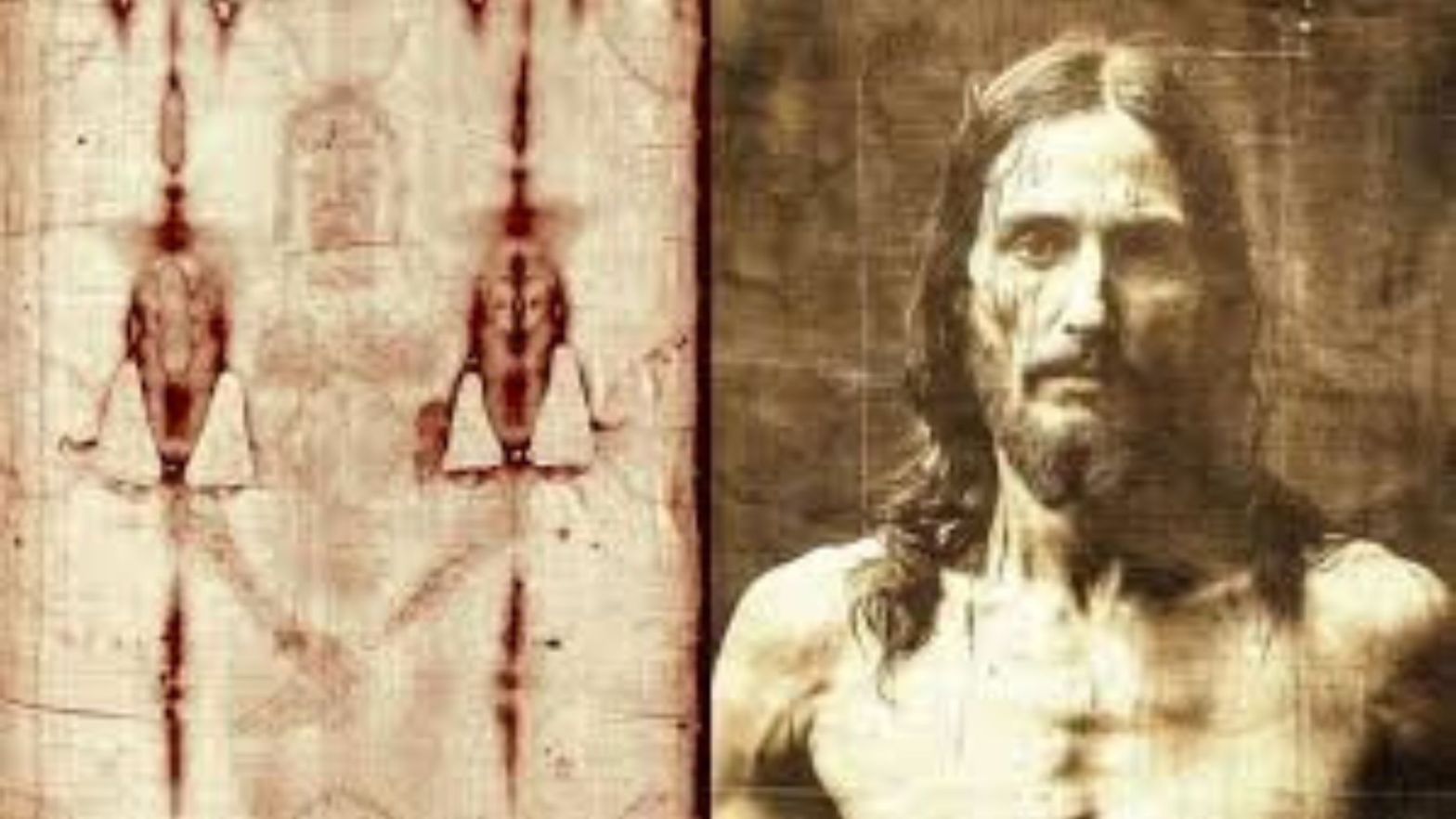

Believed by many to be the burial cloth of Jesus of Nazareth, the Shroud is a long linen sheet bearing the faint image of a crucified man.

What makes it unique is that the image appears to record the death, burial, and resurrection of a single historical figure in one object.

No other artifact in the world is claimed to preserve all three events.

A burial shroud in Jewish tradition was a linen cloth used to wrap a deceased body before it was placed in a family tomb.

According to the four canonical gospels, Jesus was wrapped in such a cloth after his crucifixion.

The Shroud of Turin measures approximately fourteen feet long and three and a half feet wide, dimensions that match burial practices in the first century Roman world.

The cloth is made of pure linen woven in a three to one herringbone pattern, a complex and expensive weave that suggests it belonged to a wealthy owner.

This detail corresponds with the gospel account that Joseph of Arimathea provided Jesus with his own burial cloth and tomb.

The shroud is a single continuous piece of linen rather than multiple strips.

The body would have been placed on one half of the cloth, with the other half folded over the head and down the front.

This arrangement explains why the image on the cloth shows both the front and back of the same body.

The man appears lying supine, hands crossed over the pelvis, feet together, head slightly tilted.

Burial shrouds from antiquity are not rare.

Archaeologists have recovered hundreds of linen burial cloths from Israel, Egypt, and surrounding regions.

In the dry climate of the Middle East, linen can survive for thousands of years.

The famous Tarkan dress from Egypt, for example, is over five thousand years old.

Therefore the mere survival of a two thousand year old cloth is not extraordinary.

What distinguishes the Shroud of Turin is not its age but the image embedded within it.

The image depicts a bearded man with long hair, muscular build, and a height estimated between five feet ten inches and five feet eleven inches.

This would have been taller than the average Jewish man of the first century.

The body shows extensive injuries consistent with Roman crucifixion.

There are scourge marks covering the back and front, puncture wounds on the scalp, blood flows from the wrists and feet, and a large wound in the right side between the fifth and sixth ribs.

Blood stains appear before the image, meaning the blood was deposited first and the image formed later.

The blood has been tested and identified as human male blood of type AB.

This blood type is rare globally and more common among Middle Eastern populations.

Chemical analysis shows both premortem and postmortem blood, indicating that the man was bleeding before and after death.

The injuries match with remarkable precision the descriptions found in the New Testament and in Roman historical sources.

The scourge marks correspond to the Roman flagrum, a whip with multiple leather thongs tipped with metal weights.

The pattern suggests two executioners striking simultaneously.

The puncture wounds around the head suggest a helmet of thorns rather than a simple crown.

More than fifty small blood flows indicate that thorns were pressed deeply into the scalp.

Nail wounds appear in the wrists rather than the palms, which aligns with Roman practice and modern anatomical understanding.

The feet show signs of being nailed through the heel bones.

The large side wound matches the spear thrust described in the Gospel of John, which states that blood and water flowed from the wound, a sign of death caused by heart failure or pulmonary edema.

One of the most extraordinary features of the Shroud is the nature of the image itself.

It is not painted, dyed, or drawn.

Microscopic examination reveals no pigment, no brush strokes, and no binding medium.

The image exists only on the top two microns of the linen fibers, thinner than a human hair.

It does not penetrate the cloth.

If the image were scraped lightly, it could be removed.

When the cloth was photographed for the first time in 1898, an astonishing discovery was made.

The photographic negative revealed a highly detailed positive image of the man, clearer than what is visible to the naked eye.

In other words, the shroud itself functions as a photographic negative created centuries before photography existed.

The image contains three dimensional information, meaning that when analyzed by computer, it produces a realistic relief map of a human body.

No known artistic technique from antiquity or the Middle Ages can produce such an image.

Experiments with paint, heat, acid, and light have all failed to replicate its properties.

Modern laser experiments have succeeded in recreating some chemical effects on linen fibers, but only by using bursts of intense ultraviolet energy far beyond any ancient technology.

Some researchers propose that a sudden release of energy at the moment of resurrection altered the cloth chemically, though this remains a hypothesis beyond current scientific verification.

The Shroud of Turin has been studied by more than one hundred scientific disciplines, including physics, chemistry, biology, medicine, textiles, botany, mathematics, and forensic science.

It is widely considered the most studied artifact in the world.

Thousands of peer reviewed papers have been published on its properties.

One of the most debated aspects of the shroud is its age.

In 1988, three laboratories conducted radiocarbon dating on a small corner sample and concluded that the cloth dated to the Middle Ages.

This result led many to declare the shroud a medieval forgery.

However later research revealed that the tested sample came from a repaired section contaminated by later threads and handling.

Subsequent chemical and spectroscopic studies suggest that the cloth itself may be much older.

Botanical evidence supports an origin in the Middle East.

Pollen grains embedded in the cloth come from plants native to Jerusalem and surrounding regions, including species that bloom only in spring.

Other pollen types trace a path from Jerusalem to Edessa in modern Turkey, then to Constantinople, and later to France and Italy.

This distribution matches historical traditions about the movement of a revered cloth through the Byzantine world.

Historical records indicate that an image known as the Image of Edessa was venerated in the early centuries of Christianity.

Some scholars believe this image was the folded Shroud of Turin.

By the thirteenth century, the shroud appears in France, later entering the possession of the House of Savoy before being transferred to Turin, where it remains today.

The Catholic Church does not officially declare the shroud to be the burial cloth of Jesus, but it allows it to be venerated as an icon that points believers toward Christ.

The cloth is displayed publicly only on rare occasions.

Millions of pilgrims have viewed it, often describing a profound emotional and spiritual experience.

Skeptics argue that the shroud could still be an elaborate medieval creation, noting that scientific uncertainty does not equal proof of authenticity.

They emphasize the unresolved questions about carbon dating and the lack of direct historical documentation linking the cloth to Jerusalem in the first century.

Believers respond that the convergence of medical, forensic, botanical, chemical, and historical evidence makes accidental coincidence or deliberate forgery extremely unlikely.

What remains undisputed is that the Shroud of Turin depicts a real human being who suffered an exceptionally brutal death by crucifixion.

The image preserves a silent record of wounds, blood flows, and physical trauma unlike any other artifact known.

Whether one views it as the burial cloth of Jesus or as an extraordinary relic of unknown origin, it continues to challenge both faith and science.

More than a religious object, the shroud has become a bridge between history, medicine, physics, and theology.

It forces modern observers to confront an ancient execution with unsettling realism.

It invites questions about suffering, redemption, and the limits of human knowledge.

And after centuries of scrutiny, it still resists definitive explanation.

In the end, the Shroud of Turin remains what it has always been, a fragile piece of linen carrying the weight of one of humanity most profound mysteries.

News

Shroud of Turin Used to Create 3D Copy of Jesus

In early two thousand eighteen a research team in Rome unveiled a life sized three dimensional representation of the human…

“The Face of God” Michael & The Shroud of Turin | Dr. Jeremiah Johnston

The Shroud of Turin has long stood at the crossroads of faith, science, and controversy. For centuries the linen cloth…

Eddie Bravo Went Down a Rabbit Hole on the Shroud of Turin

For many years the Shroud of Turin has stood at the center of one of the longest and most emotional…

JRE: The Vatican SHUT DOWN The Book Of Enoch After AI Translated Its True Meaning! What If One Of The Bible’s Most Forbidden Books Was Silenced Because It Reveals A Truth Too Dangerous For Humanity To Know? After Artificial Intelligence Finally Translated the Ancient Text Line by Line, Shocking Passages About Fallen Angels, Lost Civilizations, and Hidden Knowledge Are Forcing Scholars To Ask Why The Vatican Suppressed This Book For Centuries. Is This Proof Of A Cover-Up — Or A Warning Meant For Our Time? Click The Article Link In The Comment And Discover The Secret.

For centuries the Book of Enoch has stood at the edge of biblical history, admired by some, rejected by others,…

What Scientists Just FOUND Beneath Jesus’ Tomb in Jerusalem Will Leave You Speechless

The Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem has long stood as one of the most sacred landmarks in Christian…

AI Just Decoded the Hidden Message in Da Vinci’s The Last Supper What It Revealed Is Terrifying What If Leonardo da Vinci Secretly Hid a Warning Inside the World’s Most Famous Painting That Only Artificial Intelligence Could Finally Read? After Centuries of Silence, New AI Analysis Claims to Expose Forbidden Symbols, Apocalyptic Codes, and a Message So Disturbing It Was Never Meant for Human Eyes. Is This a Lost Prophecy, a Hidden Confession, or a Truth That Could Rewrite Art and History Forever? Click The Article Link in the Comment and Uncover the Shocking Revelation.

In a quiet hall in Milan, a single wall has carried centuries of attention, debate, and wonder. The mural known…

End of content

No more pages to load