The Shroud of Turin: An Ancient Cloth at the Intersection of History, Science, and Belief

For centuries, a single piece of linen has stood at the center of one of the most enduring debates in human history.

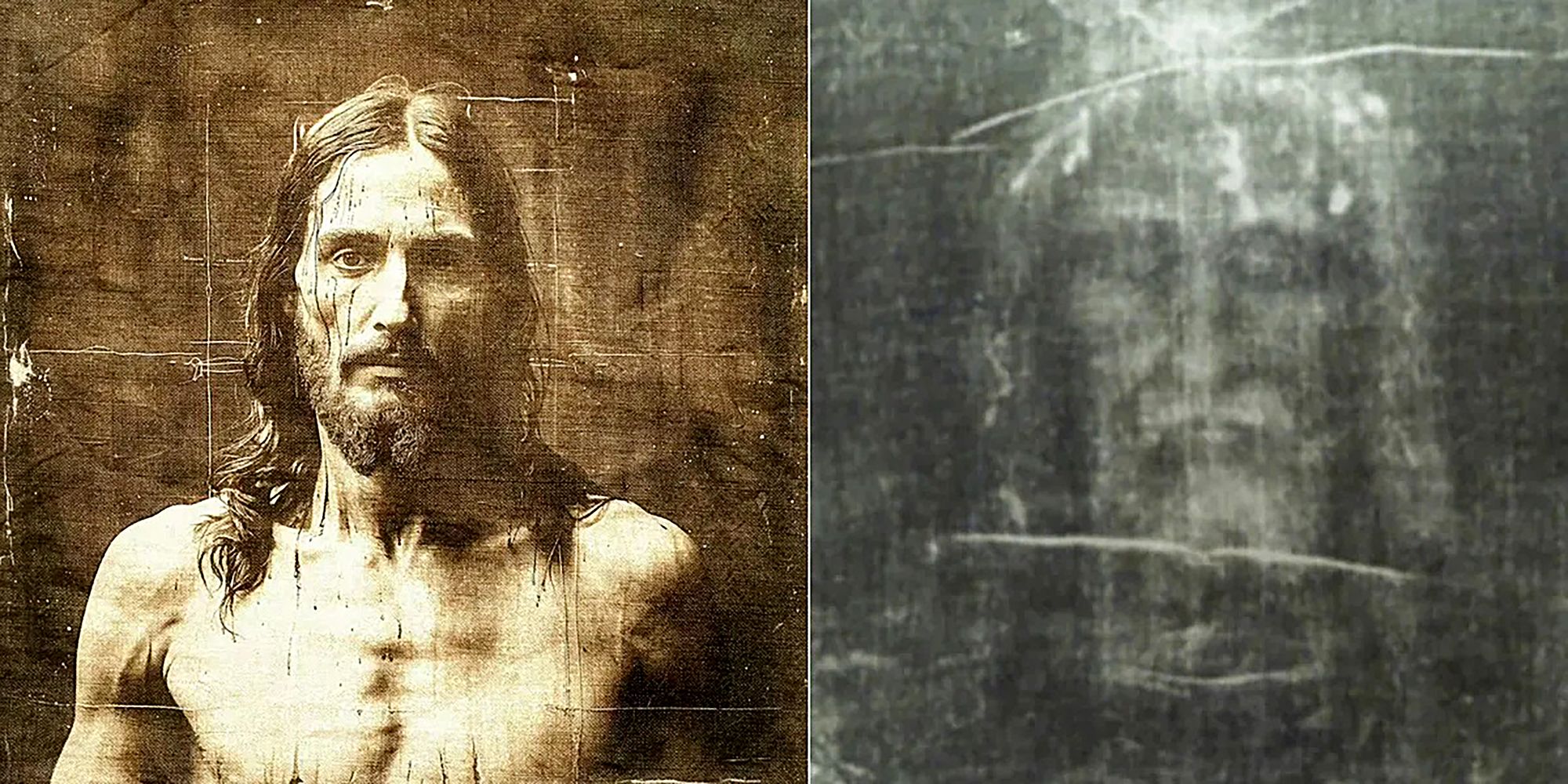

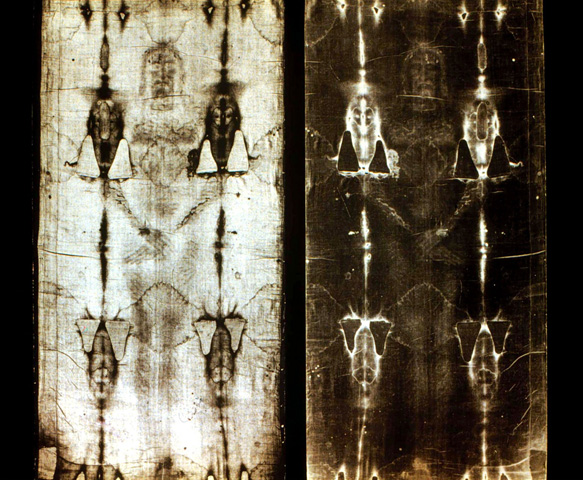

Known as the Shroud of Turin, the cloth bears the faint image of a man who appears to have suffered crucifixion.

To many believers, it is the burial cloth of Jesus of Nazareth.

To skeptics, it is an elaborate medieval fabrication.

Despite decades of intense scrutiny across multiple disciplines, the Shroud continues to defy definitive explanation.

Housed since 1578 in the Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist in Turin, Italy, the Shroud has become one of the most studied artifacts in the world.

Its appeal lies not only in its religious significance, but also in the extraordinary scientific, medical, and historical questions it raises.

Modern research has transformed the Shroud from a devotional object into a complex case study involving archaeology, chemistry, forensic medicine, textile history, and physics.

What the Shroud Is—and What It Is Not

A shroud, by definition, is a cloth used to wrap a deceased body for burial.

The Shroud of Turin is a rectangular linen cloth measuring approximately 14 feet 3 inches by 3 feet 9 inches following conservation work carried out in 2002.

It is woven in a rare three-over-one herringbone twill pattern and is remarkably thin, measuring roughly 0.

014 inches in thickness.

Each thread is composed of 70 to 120 individual linen fibers, a variation consistent with handmade ancient textiles.

While the linen itself would have been relatively common in antiquity, the weaving technique, preparation, and size indicate that the cloth would have been expensive and accessible primarily to wealthy individuals.

This distinction has fueled scholarly debate, particularly in relation to Gospel accounts describing Jesus being buried in a linen cloth purchased by Joseph of Arimathea, a wealthy follower.

The Shroud displays a faint sepia-toned image of a naked, bearded man with long hair, visible from both the front and the back.

His hands are crossed over his groin, and his body bears numerous marks consistent with scourging, puncture wounds, and trauma.

In addition to the body image, the cloth contains bloodstains, burn marks, water stains, and patches added during later repairs.

Fire, Damage, and Restoration

The Shroud’s current appearance reflects a long and eventful history.

In 1532, a fire broke out in the chapel at Chambéry, France, where the cloth was stored inside a silver reliquary.

Molten silver dripped onto the folded cloth, causing symmetrical burn holes and scorch marks.

Water used to extinguish the fire left visible stains that remain today.

Following the fire, Poor Clare nuns patched the damaged areas and sewed the Shroud onto a backing cloth known as the Holland cloth.

These interventions are clearly distinguishable from the original linen and provide valuable reference points for dating later alterations.

Notably, a set of four L-shaped burn holes predates the 1532 fire.

These holes appear in pairs and match images found in medieval manuscripts, including the Hungarian Pray Codex dated to the late 12th century.

Their presence in artwork predating the Shroud’s documented appearance in France suggests the cloth—or a very similar one—was known earlier than often assumed.

Textile Clues Pointing to Antiquity

One of the most intriguing features of the Shroud is the presence of visible banding—alternating darker and lighter stripes running along both warp and weft threads.

This phenomenon results from ancient flax processing methods, specifically retting and bleaching in small batches.

Classical authors such as Pliny the Elder describe these techniques, which differ significantly from medieval European linen production.

Surviving high-quality medieval linens show no such banding and are typically woven using different patterns.

While herringbone weaves are rare in ancient linen, similar patterns have been identified in Roman-era textiles discovered in Egypt and dated to the first century.

These textile characteristics do not prove the Shroud’s antiquity, but they challenge claims that it is a typical medieval product.

The Image That Should Not Exist

The Shroud’s most puzzling feature remains the body image itself.

Scientific examination has shown that the image is not painted, dyed, scorched, or printed.

No pigments, binders, or brush strokes are present.

Instead, the image consists of a superficial discoloration affecting only the outermost fibers of the linen—less than 1% of each thread—leaving the inner fibers unchanged.

The discoloration is the result of a chemical change in the cellulose structure of the fibers, involving oxidation, dehydration, and conjugation of polysaccharides.

This alteration causes the fibers to reflect light differently, producing the visible image.

Importantly, no additional material was added to the cloth.

When photographed in 1898, the image revealed itself to be a perfect photographic negative.

Details invisible to the naked eye, including facial features and anatomical contours, appeared clearly for the first time.

Moreover, the image encodes three-dimensional information, allowing researchers to reconstruct the body’s depth and proportions—an unprecedented characteristic for any known artwork.

Blood Before Image

In contrast to the body image, the bloodstains on the Shroud are real and chemically distinct.

Forensic tests have identified hemoglobin and multiple blood components consistent with human male blood.

The blood appears to have come from actual wounds and shows signs of gravity-driven flow.

Crucially, the bloodstains are present where the body image is absent, indicating that blood contacted the cloth before the image formed.

This sequencing rules out many artistic and chemical hypotheses.

Capillary action, serum separation, and clotting patterns further support the conclusion that the blood originated from a traumatized human body.

One wound on the right side shows a separation between red blood and clear serum, a phenomenon that occurs when a wound is inflicted after death.

This detail corresponds with descriptions found in the Gospel of John, which recounts blood and water flowing from Christ’s side after he was declared dead.

Forensic Consistency with Crucifixion

The anatomical details visible on the Shroud align closely with Roman crucifixion practices.

Nail wounds appear at the wrists rather than the palms, consistent with the need for skeletal support to bear body weight.

The feet show evidence of nail penetration, and the shoulders and back are covered with hundreds of scourge marks consistent with a Roman flagrum, a whip fitted with metal or bone tips.

The pattern and angles of the scourge marks suggest that at least two individuals of different heights administered the beating.

Facial swelling, a possible broken nose, and bloodstains around the scalp indicate blunt force trauma and puncture wounds consistent with a crown of thorns.

Medical analysis suggests the individual suffered hypovolemic shock due to severe blood loss.

Contrary to popular belief, rigor mortis would not have permanently fixed the body’s position, as it typically subsides after several hours.

Dirt, Dust, and Geography

Microscopic analysis has identified traces of calcium carbonate dust on the feet, left knee, and nose of the image.

This distribution suggests contact with the ground while the individual was upright or falling.

Some researchers argue that the chemical signature of the limestone resembles samples from the area around Jerusalem’s Damascus Gate.

However, similar limestone is also found throughout arid Mediterranean regions influenced by Saharan dust.

While intriguing, this evidence is circumstantial rather than conclusive.

A Fragmented Historical Trail

Historically, the Shroud can be traced with certainty to mid-14th-century France, where it was owned by French knight Geoffroi de Charny.

In 1453, it was acquired by the House of Savoy, which retained ownership for over 500 years before donating it to the Holy See in 1983.

Earlier references are less certain but compelling.

In 1204, during the Fourth Crusade, a French knight named Robert de Clari described a cloth in Constantinople bearing the image of Christ that was displayed publicly each Friday.

He noted that its fate became unknown after the city was looted by Crusaders.

Orthodox and Byzantine sources also reference acheiropoietos images—icons “not made by human hands”—on linen cloths in cities such as Edessa and Camana between the 6th and 10th centuries.

Some scholars propose that these references describe the same object, later brought to Constantinople and eventually to Western Europe.

While none of these accounts definitively prove continuity, they outline a plausible historical pathway from Jerusalem to medieval France.

The Carbon Dating Debate

In 1988, radiocarbon dating tests conducted by laboratories in Oxford, Zurich, and Arizona dated a sample of the Shroud to between 1260 and 1390.

The results were widely publicized as evidence of a medieval origin.

However, controversy soon followed.

Only one sample, taken from a single corner of the cloth, was tested—contrary to the original plan to use multiple samples from different areas.

Critics argue that this corner may have been subject to repairs, contamination, or environmental effects.

While hypotheses such as reweaving and microbial contamination have been proposed, none have been conclusively proven.

Most scholars today agree that carbon dating is a valuable but not infallible tool and that the 1988 test alone cannot definitively resolve the Shroud’s origin.

An Unresolved Enigma

After decades of research, no known artistic, natural, or technological process—ancient or modern—has been able to replicate all the Shroud’s characteristics simultaneously.

The image’s superficiality, three-dimensional encoding, chemical composition, and forensic accuracy remain unexplained.

Whether one views the Shroud as a sacred relic or an unsolved historical mystery, its significance is undeniable.

It continues to challenge assumptions, bridge disciplines, and invite rigorous inquiry.

Until new testing or discoveries emerge, the Shroud of Turin remains what it has long been: a silent witness, suspended between faith and science, history and mystery.

News

The Untold Story of Jennifer Aniston: Hollywood’s Most Down-to-Earth Star Revealed!

Introduction Jennifer Aniston is a name that resonates with millions around the world. From her iconic role as Rachel Green…

😼 Unlocking the Secrets of Jennifer Aniston’s Jaw-Dropping Fitness Routine 💪 What You Didn’t Know About Her Ageless Glow and Relentless Discipline 👇

Introduction Jennifer Aniston has long been celebrated not just for her acting prowess but also for her stunning physique. At…

😼 The Unexpected Side of Jennifer Aniston 😂 Her Wild Rendition of “Baby Got Back” That Left the Entire Studio in Tears of Laughter 👇 Who knew America’s sweetheart could drop bars like that? During what was supposed to be a calm, polished interview, Jennifer Aniston stunned everyone by busting out a shockingly perfect — and side-splitting — rendition of “Baby Got Back.” The audience went feral, the host nearly fell off his chair, and even Jen couldn’t hold back her laughter. For a brief, glorious moment, the queen of calm turned into the queen of comedy — and Hollywood is still talking about it.👇

Introduction When you think of Jennifer Aniston, what comes to mind? The iconic Rachel Green from “Friends”? The glamorous Hollywood…

The Astonishing Secrets Behind Jennifer Aniston’s Ageless Beauty at 54

Introduction At 54, Jennifer Aniston defies the passage of time, captivating us with her youthful looks and vibrant energy. Many…

How Jennifer Aniston and Reese Witherspoon’s Sisterhood Transcends Time

Introduction In the world of Hollywood, where friendships can often be fleeting and relationships are frequently put under the microscope,…

What Really Happened Behind the Scenes of The Morning Show

The Rumor That Started It All It began as a whisper on social media, a seemingly harmless observation by a…

End of content

No more pages to load