For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has hovered uneasily between faith, skepticism, and science.

To some, it is the most sacred relic in Christianity.

To others, it is a clever medieval fabrication.

Yet despite decades of scrutiny, no consensus has ever been reached.

Instead, every attempt to explain the Shroud seems to deepen the mystery.

In recent years, that mystery has entered an unexpected new phase.

When artificial intelligence was applied to high-resolution data from the Shroud, researchers did not find evidence of paint, pigment, or artistic deception.

What they uncovered instead was information—depth, structure, and anatomical precision embedded within the fabric itself—forcing scientists to confront a disturbing question: how did such an image come to exist at all?

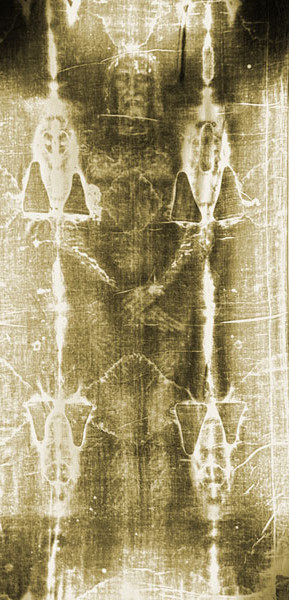

At first glance, the Shroud appears unimpressive.

The image is faint, almost invisible unless viewed from a distance or under controlled lighting.

A ghostly outline of a human form appears on a linen cloth more than fourteen feet long, showing both the front and back of a naked man laid out as if for burial.

The figure bears marks of extreme trauma: wounds consistent with scourging, puncture injuries at the wrists and feet, a deep wound in the side, and facial damage suggesting violent blows.

These injuries closely align with Roman crucifixion practices and with descriptions found in the Gospels.

That resemblance alone has fueled debate for generations.

What makes the Shroud truly unusual is not merely what it depicts, but how the image exists.

Under microscopic examination, the cloth shows no paint layers, no pigments, no dyes, and no brushstrokes.

The image does not soak into the fabric.

Instead, discoloration appears only on the outermost surfaces of individual linen fibers, penetrating less than a hair’s breadth.

This superficial alteration rules out nearly every known artistic or chemical process, ancient or modern.

Even heat and scorching fail to account for the image’s uniformity and precision.

In 1898, photography revealed another startling property.

When the Shroud was photographed, the negative plate produced a clear, lifelike positive image.

Light and dark areas reversed perfectly, revealing facial details, body proportions, and wounds with startling realism.

In effect, the Shroud behaved like a photographic negative centuries before photography existed.

Medieval artists did not understand negative imaging, nor did they possess the optical knowledge required to create such an effect intentionally.

From that moment forward, the Shroud ceased to be merely a religious artifact and became a scientific problem.

Over the decades, specialists from chemistry, physics, textile analysis, and medicine examined the cloth.

Pollen grains traced to the Middle East were identified.

Bloodstains behaved like real human blood, complete with serum separation patterns impossible to reproduce with paint.

The blood appeared to have been applied before the image formed, suggesting two separate processes rather than a single artistic act.

Carbon dating tests conducted in the late twentieth century suggested a medieval origin, but those results were later challenged due to possible contamination, fire damage, and repairs in the sampled area.

Each new test seemed to clarify one detail while raising several more questions.

The introduction of artificial intelligence marked a turning point.

Researchers did not deploy AI to prove the Shroud authentic or false.

Instead, they used forensic image-analysis systems designed to detect spatial relationships, depth cues, and hidden structural data—tools commonly applied in medical imaging, archaeology, and crime scene reconstruction.

When high-resolution scans of the Shroud were processed, scientists expected modest improvements in clarity.

What they received instead was unprecedented.

The AI detected consistent three-dimensional information encoded across the entire image.

When translated into a model, the result was not distortion or noise, but a coherent human body.

Facial features aligned anatomically.

Muscle contours appeared realistic.

Body proportions matched those of an adult male.

Crucially, image brightness correlated directly with distance: areas closer to the cloth appeared darker, while areas farther away appeared lighter.

In effect, the Shroud functions like a topographical map of a human body, recording spatial depth without pigments or shading.

This property alone distinguishes the Shroud from any known artwork.

Paintings and photographs cannot reliably encode true depth information; when subjected to similar analysis, they collapse into randomness.

The Shroud does not.

Its data remains stable and interpretable, suggesting that the image formation process captured physical distance rather than visual illusion.

No medieval technique is known that could achieve this, and even modern methods struggle to replicate all of the Shroud’s properties simultaneously.

Once a three-dimensional body emerged from the data, medical experts entered the discussion.

Forensic pathologists and trauma specialists examined the reconstruction without being told what conclusions to draw.

Their reactions were notably restrained.

Instead of excitement, many responded with prolonged silence.

The injuries visible in the model were internally consistent and medically precise.

The wrists showed trauma consistent with nails passing between carpal bones rather than through the palms, contradicting centuries of artistic tradition but aligning with modern anatomical understanding.

The shoulders and arms displayed signs of prolonged suspension under body weight, consistent with crucifixion mechanics.

The back bore dozens of wounds matching the pattern and spacing of a Roman flagrum, a whip fitted with bone or metal tips.

Facial swelling, nasal damage, and asymmetrical bruising indicated repeated blunt force trauma from multiple angles.

Even the posture suggested cycles of collapse and effort consistent with death by asphyxiation, a hallmark of crucifixion.

These findings troubled skeptics and believers alike.

Medieval artists lacked knowledge of biomechanics, suspension trauma, and respiratory failure.

Yet the Shroud encodes these realities with clinical accuracy.

If the image were forged, it would require medical insight centuries ahead of its time, applied invisibly through an unknown method.

Attention then returned to the fabric itself.

Under AI-assisted microscopic analysis, the image appeared even more perplexing.

The discoloration affects only the outermost fibrils of individual fibers, stopping abruptly without bleeding or penetration.

There is no residue of pigment, no chemical agent, no sign of manual application.

The uniformity of the image suggests a single, instantaneous event rather than gradual construction.

Some researchers cautiously compared the effect to brief, high-energy interactions observed in laboratory settings, though no known natural or artificial process fully accounts for the evidence.

Importantly, no one has successfully reproduced all characteristics of the Shroud: surface-level discoloration, negative imaging, three-dimensional depth, and anatomical accuracy in one coherent result.

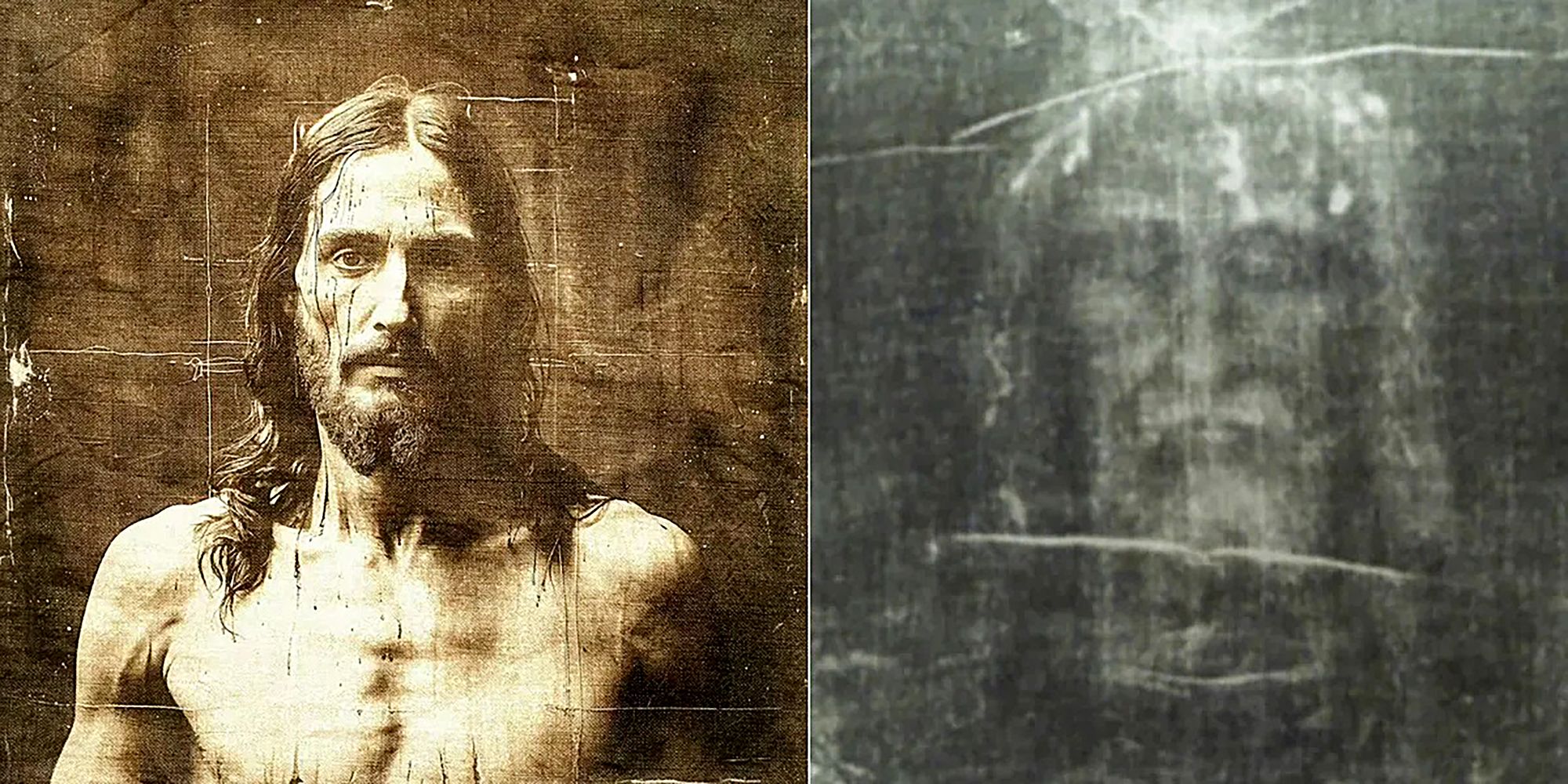

Perhaps the most emotionally charged moment came when AI reconstructed the face.

The system did not embellish or idealize.

It simply decoded spatial data already present.

The result was a Middle Eastern man in his early thirties, with strong but unremarkable features, deep-set eyes, a full beard, and long hair.

Despite visible trauma, the expression was calm.

The eyes were closed, the mouth relaxed.

It did not depict suffering in progress, but stillness after suffering had ended.

Observers noted an unsettling familiarity.

Many traditional depictions of Jesus across centuries shared similar proportions, raising questions about whether artists had unknowingly echoed an image preserved far earlier.

The AI did not generate the face; it revealed it.

That distinction mattered.

What emerged was not interpretation, but translation.

Rather than resolving debate, the AI findings intensified it.

Skeptics rightly argued that technology cannot confirm identity or divinity.

Correlation does not equal proof.

Yet defenders responded with a challenge that grew harder to dismiss: if the Shroud is not authentic, what exactly is it? Any alternative explanation must now account for a convergence of properties unmatched by known art, science, or technology.

Historians revisited carbon dating controversies.

Scientists debated energy-based hypotheses.

Theologians cautioned against reducing faith to data.

Yet across disciplines, one agreement emerged: the Shroud could no longer be casually dismissed.

Artificial intelligence had not exposed a trick.

It had exposed complexity.

In the end, the Shroud of Turin occupies a rare position.

It is not conclusively explained, nor conclusively disproven.

Instead, it stands as a boundary object, revealing the limits of current understanding.

AI, designed to reduce uncertainty, encountered a phenomenon that grows more coherent without becoming simpler.

The Shroud behaves less like an artwork awaiting debunking and more like a record awaiting comprehension.

In an age confident in its mastery of data and technology, the Shroud offers an uncomfortable reminder.

Some mysteries do not vanish under scrutiny.

Some endure, not because they resist reason, but because they expose its limits.

Artificial intelligence has brought the Shroud firmly into the present.

It has not closed the debate.

It has ensured that it will continue—deeper, sharper, and far more difficult to ignore.

News

Black CEO Denied First Class Seat – 30 Minutes Later, He Fires the Flight Crew

You don’t belong in first class. Nicole snapped, ripping a perfectly valid boarding pass straight down the middle like it…

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 7 Minutes Later, He Fired the Entire Branch Staff

You think someone like you has a million dollars just sitting in an account here? Prove it or get out….

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 10 Minutes Later, She Fires the Entire Branch Team ff

You need to leave. This lounge is for real clients. Lisa Newman didn’t even blink when she said it. Her…

Black Boy Kicked Out of First Class — 15 Minutes Later, His CEO Dad Arrived, Everything Changed

Get out of that seat now. You’re making the other passengers uncomfortable. The words rang out loud and clear, echoing…

She Walks 20 miles To Work Everyday Until Her Billionaire Boss Followed Her

The Unseen Journey: A Woman’s 20-Mile Walk to Work That Changed a Billionaire’s Life In a world often defined by…

UNDERCOVER BILLIONAIRE ORDERS COFFEE sa

In the fast-paced world of business, where wealth and power often dictate the rules, stories of unexpected humility and courage…

End of content

No more pages to load