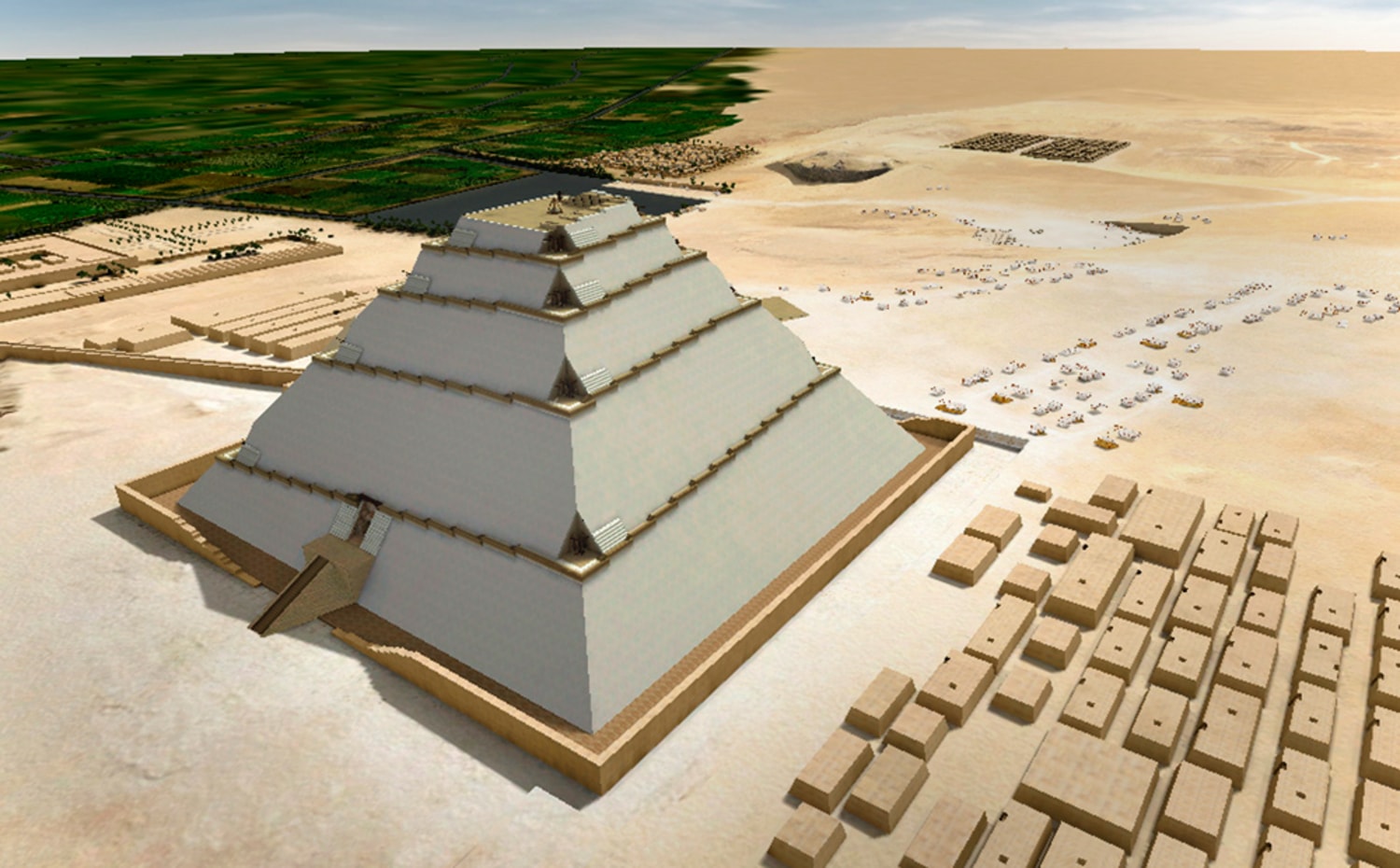

For centuries, the Great Pyramid of Giza has fascinated humanity, inspiring wonder, speculation, and sometimes disbelief.

Conventional history attributes the construction of the pyramids to ancient Egyptians around 2500 BC, led by Pharaoh Khufu, using copper tools, ramps, and thousands of laborers.

This narrative is taught in schools, featured in documentaries, and reinforced by tour guides who explain the painstaking effort involved in building these iconic structures.

Yet, not everyone accepts this explanation.

Graham Hancock, a journalist rather than an archaeologist, has spent decades investigating ancient mysteries and challenging established historical timelines.

He has proposed that the Great Pyramid and other ancient monuments may not have been built by the Egyptians as history tells us.

Instead, Hancock suggests that they could be remnants of a highly advanced civilization that predates the known history of humankind.

Graham Hancock began his professional career as a journalist, studying sociology at Durham University and graduating with honors in 1973.

He wrote extensively for major publications such as The Economist and The Sunday Times, often covering political and economic issues in Africa.

During his years reporting on famine, war, and global aid efforts, Hancock developed skills in investigative research and critical analysis.

These skills would later form the foundation for his work in alternative history.

His shift from mainstream journalism to exploring ancient mysteries began in the early 1990s while researching his book The Sign and the Seal, which examined the legend of the Ark of the Covenant.

The book’s success inspired him to expand his focus to the origins of ancient civilizations, monuments, and knowledge systems that mainstream scholarship had largely ignored or dismissed.

In 1995, Hancock published Fingerprints of the Gods, a book that brought him international recognition and sparked heated debates.

The work questioned the accepted timelines of human civilization and proposed that a sophisticated culture, lost to history, may have existed thousands of years before the rise of dynastic Egypt.

Hancock did not suggest that extraterrestrials built the pyramids, a common misconception associated with fringe theories.

Instead, he relied on observable data, such as erosion patterns, architectural precision, astronomical alignments, and geological studies, to argue that the pyramids might have been constructed by an advanced human civilization whose knowledge surpassed what scholars typically attribute to ancient peoples.

A central element of Hancock’s theory involves the Great Sphinx of Giza.

Together with geologist Robert Schoch, Hancock highlighted erosion patterns on the Sphinx’s body that appear to have been caused by long-term water exposure rather than wind and sand.

According to Schoch’s analysis, rainfall sufficient to produce this type of erosion occurred thousands of years before the first Egyptian dynasties.

This led to a radical suggestion: if the Sphinx is older than Egypt itself, then the pyramids may also predate the dynastic period.

Hancock has consistently referred to this evidence, arguing that it challenges the official historical timeline and warrants serious consideration rather than dismissal.

Another aspect of Hancock’s research involves astronomical alignments, particularly the so-called Orion correlation theory.

Proposed by Robert Bauval and frequently cited by Hancock, this theory suggests that the arrangement of the three pyramids at Giza corresponds to the stars in Orion’s Belt.

While some scholars argue that this is coincidental, Hancock points to the precision of the alignment, noting that it matches the sky as it would have appeared around 10,500 BC.

This timing aligns with the estimated period of water erosion on the Sphinx, further reinforcing the hypothesis that the Giza complex may be far older than conventionally believed.

Hancock emphasizes that these alignments, along with the geometric and mathematical sophistication of the pyramids, suggest a level of knowledge and planning that would have been difficult to achieve with the tools and methods attributed to ancient Egyptians.

Hancock also draws attention to Göbekli Tepe in modern-day Turkey, an archaeological site dated to at least 9600 BC.

The site features massive stone pillars arranged in circular enclosures, adorned with intricate carvings of animals and abstract symbols.

The level of organization required to construct Göbekli Tepe, despite the absence of agriculture, writing, or metal tools, supports Hancock’s view that complex human societies existed long before the advent of dynastic civilizations.

This site, in his view, provides concrete evidence that hunter-gatherer groups could have possessed sophisticated architectural and organizational skills, challenging the traditional linear model of human progress.

The question of how the pyramids were built further fuels Hancock’s theories.

Mainstream Egyptology posits that copper chisels, wooden sledges, and manpower allowed ancient Egyptians to quarry, transport, and assemble massive limestone and granite blocks.

Hancock and consulted engineers, however, highlight inconsistencies in this explanation.

Granite, used in the King’s Chamber and other interior structures, ranks six to seven on the Mohs hardness scale, while copper tools rank only around three.

This makes precise cutting of granite with copper instruments highly improbable.

Additionally, some blocks weigh up to eighty tons, requiring transportation over long distances without any definitive records explaining the process.

Hancock points out that the base of the Great Pyramid is almost perfectly level across thirteen acres, with interior beams cut to precision tolerances that modern machinery would find challenging to replicate.

These observations suggest to Hancock that the pyramids may have been built using advanced techniques that have since been lost to history.

Hancock further observes that the pyramid-building timeline in Egypt does not follow conventional learning curves.

Typically, early structures are rudimentary, with sophistication increasing over time.

The Great Pyramid, however, is the most advanced, while later pyramids are smaller, less precise, or structurally compromised.

Hancock interprets this as evidence that knowledge may have been inherited from a preexisting civilization rather than gradually developed by dynastic Egyptians.

Moreover, despite the Egyptians’ reputation for documenting almost every aspect of their society, there are no records detailing the construction of the Great Pyramid.

The name of Pharaoh Khufu appears on a single small beam in an upper chamber, which some experts believe was added later.

This scarcity of documentation challenges the traditional narrative and supports Hancock’s argument for reconsidering the pyramid’s origins.

Hancock situates his theories within the broader context of a global cataclysm known as the Younger Dryas, which occurred approximately twelve thousand years ago.

During this period, the Earth experienced sudden cooling, which some researchers attribute to a comet impact or fragments striking the planet.

Evidence for this event includes elevated levels of platinum, microspherules, and melt-glass in geological layers across North America and Europe.

Hancock proposes that this cataclysm may have destroyed an advanced civilization, with survivors passing down fragments of knowledge to emerging cultures such as those in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and the Indus Valley.

This theory provides a potential explanation for why physical evidence of such a civilization is scarce and why monumental knowledge appears in seemingly isolated regions around the world.

Hancock also links his theories to myths and legends, particularly flood narratives present in nearly every ancient culture.

Stories such as those of Noah, Manu, Utnapishtim, and Ziusudra share a common theme: an advanced group warned of a catastrophe preserves knowledge or life.

Hancock interprets these myths as distorted memories of real global events, transmitted orally and in religious texts across generations.

He also draws connections to Plato’s story of Atlantis, which describes a highly advanced maritime civilization destroyed in a single day and night.

While scholars often dismiss Atlantis as allegory, Hancock sees it as a potential record of the same pre-cataclysmic society that built the pyramids and other megalithic sites.

The implications of Hancock’s theories are profound.

If his hypotheses are even partially correct, human history must be reevaluated.

The accepted timeline of technological and social development would no longer be linear, and the idea of a lost civilization with advanced knowledge challenges assumptions about early human capabilities.

Pyramids and other monuments could be seen not as tombs or simple structures, but as carriers of encoded knowledge, messages, or markers for future generations.

Hancock suggests that mathematical constants, astronomical alignments, and precise geometries may hold a legacy of ancient science, revealing insights into early human understanding of the cosmos.

Hancock’s work has sparked both public fascination and academic criticism.

Traditional archaeologists and Egyptologists label his claims as pseudoscientific, arguing that they rely on speculation and selective interpretation rather than verifiable evidence.

They maintain that the pyramids are the result of gradual architectural evolution, cultural development, and organized labor within known historical frameworks.

Critics contend that Hancock ignores or underplays existing data, and that extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof, which they argue has not been provided.

Nonetheless, even skeptics acknowledge that Hancock raises legitimate questions about gaps in the historical record, particularly regarding construction methods, erosion patterns, and astronomical alignments.

Hancock’s Netflix series Ancient Apocalypse, released in 2022, introduced his research to a global audience, reaching the platform’s top rankings and sparking widespread discussion.

Viewers were exposed to alternative interpretations of human history, from the origins of the pyramids to the potential existence of a lost civilization erased by cataclysmic events.

While academics criticized the series for misrepresenting consensus and creating a false opposition between open-mindedness and rigor, audiences appreciated the invitation to reconsider traditional narratives.

The show ignited debates on social media, forums, and in classrooms, highlighting the tension between public curiosity and academic authority.

Hancock’s work has, in effect, shifted the conversation, not by proving definitive answers, but by encouraging deeper inquiry into the origins of civilization.

In conclusion, Graham Hancock’s investigations challenge established timelines, raise questions about lost knowledge, and suggest that the history of humanity may be far more complex than commonly believed.

His work emphasizes the importance of asking difficult questions, re-examining evidence, and remaining open to discoveries that defy expectations.

While mainstream scholars continue to critique his conclusions, Hancock’s influence has prompted renewed exploration and debate, reminding humanity that the past is not fixed, and that the monuments of our ancestors may still hold secrets waiting to be uncovered.

By exploring anomalies, studying ancient architecture, and connecting myths with geological and astronomical data, Hancock has offered an alternative lens through which to view the story of civilization, one that proposes cycles of knowledge lost and regained, and a world where the origins of human achievement are only partially understood.

News

JRE: “Scientists Found a 2000 Year Old Letter from Jesus, Its Message Shocked Everyone”

There’s going to be a certain percentage of people right now that have their hackles up because someone might be…

If Only They Know Why The Baby Was Taken By The Mermaid

Long ago, in a peaceful region where land and water shaped the fate of all living beings, the village of…

If Only They Knew Why The Dog Kept Barking At The Coffin

Mingo was a quiet rural town known for its simple beauty and close community ties. Mud brick houses stood in…

What The COPS Found In Tupac’s Garage After His Death SHOCKED Everyone

Nearly three decades after the death of hip hop icon Tupac Shakur, investigators searching a residential property connected to the…

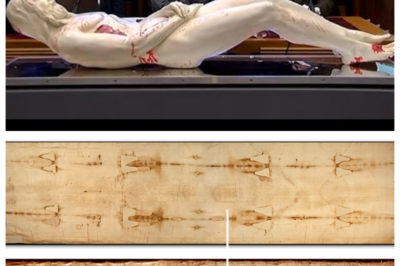

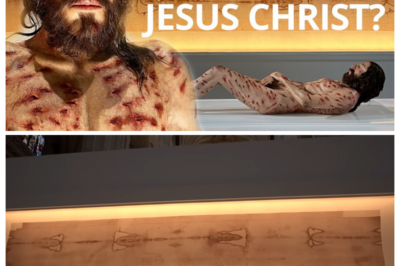

Shroud of Turin Used to Create 3D Copy of Jesus

In early 2018 a group of researchers in Rome presented a striking three dimensional carbon based replica that aimed to…

Is this the image of Jesus Christ? The Shroud of Turin brought to life

**The Shroud of Turin: Unveiling the Mystery at the Cathedral of Salamanca** For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has captivated…

End of content

No more pages to load