The Great Pyramid of Giza has long fascinated historians, engineers, and the general public alike.

Traditionally, it is attributed to Pharaoh Khufu, also known as Cheops, who allegedly commissioned its construction around 2,500 BCE.

According to mainstream accounts, the pyramid was built with copper tools, wooden sleds, and the labor of 20,000 to 30,000 workers over a span of twenty years.

It is said to contain approximately 2.

3 million limestone blocks, some weighing up to 15 tons, all aligned with remarkable precision.

Yet, a growing number of researchers question this narrative, suggesting that the true story of the Great Pyramid may be far older, more complex, and far more mysterious than conventional history admits.

Among these voices, the British researcher and journalist Graham Hancock stands out for his decades-long investigation into what he calls “forbidden history.

Hancock’s approach challenges accepted timelines and explores the possibility that the pyramids, along with other ancient monuments, are the product of a highly advanced civilization that predates the dynastic Egyptians.

Unlike traditional Egyptologists, Hancock combines archaeology, geology, astronomy, and comparative mythology to seek patterns that mainstream scholarship often overlooks.

His argument begins with a simple yet profound question: if the pyramid was truly built by Khufu, why does it bear no inscription, dedication, or funerary text inside? Most tombs and temples from the Old Kingdom are covered with hieroglyphs, praises to deities, and explicit statements of ownership.

The interior of the Great Pyramid, however, is bare.

The so-called sarcophagus in the king’s chamber is a plain, unmarked granite box, empty of any remains or burial items.

The only evidence tying Khufu to the structure comes from a handful of quarry marks reportedly discovered in a hidden chamber in the 19th century.

These markings are contested, recorded by a single explorer without corroborating witnesses, leaving scholars to question their authenticity.

The construction of the pyramid itself presents further challenges.

The structure is aligned to true north with an extraordinary margin of error of just 0.

05°, a feat nearly impossible with the primitive instruments traditionally attributed to its builders.

The base of the pyramid, covering over thirteen acres, is level to within less than an inch across its entirety.

The limestone casing stones and massive granite blocks are fitted with precision so fine that in many cases a razor blade cannot pass between them.

Some joints are angled or curved, creating an interlocking system capable of bearing immense weight.

Experimental attempts to replicate this work using copper chisels and wooden sleds have repeatedly demonstrated the impracticality of such methods, even under idealized conditions.

The official story suggests that workers set a block every 2.

5 minutes, continuously for twenty years, a task that modern engineers acknowledge as effectively impossible with the tools described.

Beyond the sheer mechanics of construction, the Great Pyramid encodes knowledge of mathematics, astronomy, and geometry.

Its proportions approximate the value of Pi, and it appears to reflect principles of the solar year and the curvature of the Earth.

Internal features such as the Grand Gallery and the King’s Chamber demonstrate an understanding of structural mechanics that far surpasses other Old Kingdom pyramids, many of which are now in ruins.

Hancock and other researchers argue that the sophistication of the Great Pyramid is inconsistent with the relative simplicity of later Egyptian structures, suggesting either a lost technology or a much earlier origin than traditionally believed.

The mystery deepens when considering the source and transport of building materials.

The granite used for the King’s Chamber, for instance, was quarried in Aswan, more than 500 miles from Giza, and individual blocks weigh up to 80 tons.

Moving such enormous stones along the Nile, overland, and then lifting them into position with the supposed tools of the time would have required an engineering capability well beyond what historians attribute to the Old Kingdom.

Proposed theories, such as massive ramps, internal spiral ramps, or pulley systems, lack archaeological evidence and fail to account for the scale of precision observed.

Modern engineers attempting to replicate the process with recreated tools have confirmed its extraordinary difficulty.

Hancock concludes that the pyramid’s construction reflects knowledge and expertise that has been lost to history.

A key piece of Hancock’s argument involves the Great Sphinx, a colossal limestone statue near the pyramids, traditionally dated to around 2,500 BCE.

Geologist Robert Schoch examined the Sphinx in the 1990s and noted patterns of vertical erosion consistent with prolonged rainfall rather than wind or sand.

Egypt’s climate has not produced sufficient rainfall for such erosion since at least 10,500 BCE, suggesting that the Sphinx may be far older than dynastic Egypt.

Hancock connects this geological evidence to the pyramids themselves, proposing that both may have been constructed by a highly advanced, pre-dynastic civilization.

This theory aligns with the so-called Younger Dryas impact hypothesis, which posits a catastrophic global event around 12,800 years ago that could have disrupted early human cultures, effectively erasing evidence of their achievements.

Hancock further explores the idea that the Giza monuments encode astronomical knowledge.

Robert Bauval’s Orion correlation theory demonstrates that the layout of the three main pyramids mirrors the belt of the Orion constellation as it would have appeared around 10,500 BCE.

This alignment coincides with the water erosion evidence observed on the Sphinx, suggesting a deliberate plan connecting the monuments to celestial patterns.

Hancock interprets these alignments as evidence that the builders possessed sophisticated astronomical and mathematical knowledge, potentially serving as a record or message for future generations.

The same approach appears in ancient sites worldwide, from Gobekli Tepe in Turkey to Teotihuacan in Mexico, hinting at shared knowledge among early civilizations long before recorded history.

Hancock’s conclusion is striking: the Great Pyramid and related monuments were likely not built by Pharaoh Khufu or any dynastic ruler but by a civilization that predates known history by thousands of years.

These builders, whom Hancock calls the “magicians of the gods,” possessed advanced engineering, astronomy, and architectural expertise, which they preserved in stone through structures designed to survive cataclysms.

When dynastic civilizations arose, they inherited these monuments and may have adapted or claimed them without fully understanding their original purpose.

The Great Pyramid, in this view, was not a tomb but a carefully constructed time capsule and repository of knowledge.

Recent discoveries support the notion that the pyramids still contain hidden secrets.

In 1993, German engineer Rudolf Gantenbrink sent a robotic probe into the shafts of the Great Pyramid, revealing sealed doors leading to unknown spaces.

Further studies using muon tomography in 2017 detected a massive void above the Grand Gallery, comparable in size to a commercial airplane.

Yet, no further exploration has been conducted, and official reports remain limited, fueling speculation that key information is being withheld.

Hancock argues that institutional gatekeeping, bureaucratic control, and the potential upheaval of established historical narratives contribute to the suppression of these findings.

Hancock does not claim to have all the answers, nor does he assert specifics about the lost civilization’s identity.

Instead, he emphasizes the need to question received narratives, reconsider timelines, and integrate multiple lines of evidence—from geology and architecture to astronomy.

For Hancock, the pyramids, the Sphinx, and other ancient monuments represent evidence of a human past far more sophisticated than textbooks admit.

They suggest that civilization may have experienced an advanced, global phase thousands of years before the dynastic period and that its knowledge was partially preserved through monumental architecture.

If Hancock’s theories are correct, they have profound implications for our understanding of human history.

The Great Pyramid was not merely an Egyptian tomb; it was a technological and astronomical statement, a message designed to endure through millennia.

The creators were not primitive, but highly skilled, and their work has survived through catastrophic events, climatic changes, and cultural transformations.

The evidence, ranging from precise engineering and material sourcing to celestial alignments and geological dating, challenges conventional chronologies and invites a reassessment of the origins of civilization.

In sum, the Great Pyramid of Giza, the Sphinx, and associated monuments may represent the legacy of a lost civilization with capabilities that modern humans struggle to comprehend.

Graham Hancock’s work encourages scholars, enthusiasts, and the public alike to look beyond conventional narratives, to question accepted history, and to consider the possibility that the story of humanity’s past is far older, more complex, and more mysterious than previously imagined.

Far from being mere tombs or symbols of dynastic power, these monuments may be enduring messages, bridging ancient knowledge with the present and reminding us that human ingenuity and understanding may extend much deeper into history than textbooks have allowed.

News

The Ethiopian Bible Reveals a Secret About Mary Magdalene No One Talks About

Mary Magdalene occupies a unique position in early Christian history, standing at the intersection of memory, authority, and emerging doctrine….

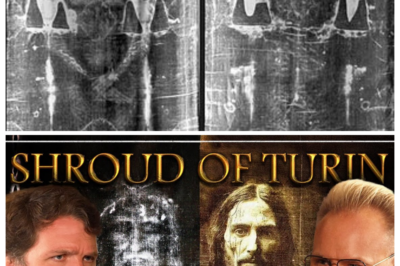

Jeremiah Johnston: Shroud of Turin, Dead Sea Scrolls, & Attempts to Hide Historical Proof of Jesus

The Shroud of Turin is one of the most extraordinary and controversial religious artifacts in the world. Believed by many…

Woman Who Claimed to Be Madeleine McCann Found Guilty of Harassment

Woman Who Claimed to Be Madeleine McCann Sentenced for Harassment For nearly two decades, the Macan family has endured the…

Madeleine McCann Disappearance: Reports Bone & Clothing Fragments Found

New Developments in the Madeleine McCann Case: Bone and Clothing Fragments Discovered The mysterious disappearance of Madeleine McCann, a case…

Is the Shroud of Turin Real?

The Shroud of Turin: A Historical, Scientific, and Forensic Investigation The Shroud of Turin, a centuries-old linen cloth bearing the…

Shroud of Turin Expert: ‘Evidence is Beyond All Doubt’

The Shroud of Turin: Science, Faith, and the Burial Cloth of Jesus Few religious artifacts in history inspire as much…

End of content

No more pages to load