For much of the postwar era, Rudolf Hess was treated as an historical oddity rather than a central figure of the Second World War.

Public memory reduced him to the image of a delusional Nazi who flew alone into enemy territory, lost his sanity, and spent the remainder of his life confined in isolation before ending it quietly.

That version of events offered closure and simplicity.

Yet when the details of his life, imprisonment, and death are examined closely, the official narrative begins to fracture.

What emerges instead is a story of political fear, suppressed testimony, and a silence carefully maintained for nearly half a century.

Rudolf Hess was not a marginal figure in the Third Reich.

He was Adolf Hitler’s deputy and confidant, a man present at the ideological and administrative foundation of the Nazi state.

He helped shape policy, propaganda, and expansion during the regime’s rise.

When war broke out, Hess possessed intimate knowledge of Germany’s ambitions and its covert diplomatic thinking.

For that reason alone, his fate carried implications far beyond his personal guilt.

What he knew, and to whom he might reveal it, mattered profoundly.

After the war, Hess became the most heavily guarded prisoner in modern history.

For forty six years, he was confined under the authority of four victorious powers, Britain, the United States, France, and the Soviet Union.

These nations rotated control of Spandau Prison in Berlin, maintaining a facility built for hundreds to contain a single aging inmate.

The expense was enormous, the security obsessive.

Officially, this arrangement symbolized justice.

Unofficially, it suggested fear of what might happen if Hess were ever allowed to speak freely.

The circumstances of his death in 1987 intensified these suspicions.

Hess was ninety three years old, physically frail, nearly blind, and severely limited by arthritis.

Guards documented that he struggled with basic movements and required assistance with daily tasks.

Nevertheless, the official verdict declared that he had taken his own life inside a small garden shed, using an electrical cord looped over a window latch.

The conclusion was reached quickly and presented as final.

Almost immediately, inconsistencies appeared.

Hess’s physical condition made the mechanics of the alleged act highly questionable.

Bruising was noted on his wrists and torso that did not align with a straightforward self hanging.

Reports suggested the shed door had been locked from the outside.

Guards later mentioned unfamiliar personnel near the area shortly before the body was discovered, while items from the scene were removed with unusual speed.

Despite these anomalies, the investigation was curtailed and the case closed.

For Hess’s son, Wolf Rüdiger Hess, the verdict never rang true.

In their final meeting days earlier, his father had appeared mentally alert and deeply fearful, expressing the belief that his life was in danger.

Three days later, he was dead.

Requests for an independent inquiry were rejected, and conflicting medical assessments were quietly set aside.

The silence that had defined Hess’s imprisonment followed him into death.

To understand why his silence mattered, it is necessary to return to May 1941.

At that time, Europe was engulfed in war.

Britain was enduring relentless bombing, and Germany was preparing for further expansion.

In this context, Hess undertook one of the most extraordinary flights in military history.

Alone in a modified fighter aircraft, he crossed hostile airspace and parachuted into Scotland.

This was not an impulsive act.

Evidence shows that he had trained for months, studying navigation, fuel limits, radar coverage, and patrol routes.

His aircraft was specially equipped, and the mission meticulously planned.

British radar detected Hess early in his flight, yet no interception occurred.

Anti aircraft defenses did not fire.

He flew for hours unchallenged before landing near Glasgow.

When captured, he requested to meet the Duke of Hamilton, a prominent British aristocrat.

The specificity of that request immediately elevated the incident from curiosity to crisis.

Hess was transferred into deep military custody, removed from public view, and questioned under extreme secrecy.

The British government announced that Hess was mentally unstable and that his mission was meaningless.

Psychiatrists diagnosed him with delusions and paranoia.

Publicly, this diagnosis dismissed anything he might say.

Privately, the government treated him not as a patient, but as a threat.

He was interrogated repeatedly by intelligence officers who cross referenced his statements and documented his claims.

Those records were sealed and classified for decades.

According to intelligence sources and later declassified material, Hess claimed he carried messages tied to peace discussions that had been explored through unofficial channels before the war.

These proposals involved a division of spheres of influence in Europe and opposition to Soviet expansion.

More sensitive still was his assertion that certain figures within Britain’s elite had shown sympathy toward such arrangements.

In the political climate of wartime Britain, public exposure of aristocratic collaboration or appeasement would have been catastrophic.

Rather than allowing these claims to be tested openly, the government chose containment.

Hess was isolated, discredited, and medicated.

Access to information was restricted.

Correspondence with his family was censored.

Over time, his mental state deteriorated, a decline later cited as proof of his instability.

Documents released decades later indicate that he was administered experimental sedatives under wartime exemptions.

Whether intended to calm him or suppress his faculties, the result was a man increasingly fragmented and easier to dismiss.

After the war, Hess was transferred to Spandau Prison.

Other senior Nazis served fixed sentences and were eventually released.

Hess never was.

By the nineteen sixties, he was the prison’s only inmate, watched by dozens of guards.

Human rights groups criticized the arrangement as cruel and unnecessary.

Behind closed doors, three of the four Allied powers favored his release on humanitarian grounds.

Only the Soviet Union consistently refused.

The Soviet position was shaped by Cold War strategy.

Maintaining Spandau allowed a continued presence in West Berlin.

There was also concern about what Hess might reveal if freed.

Over the years, additional rumors surfaced among prison staff.

Some noticed inconsistencies in medical records.

Others pointed to the absence of a distinctive First World War chest wound Hess was known to have.

Intelligence memoirs later revealed that doubts about his identity had been raised internally as early as the nineteen forties, suggesting the possibility of substitution or deliberate ambiguity.

Whether true or not, these doubts underscored how fragile the narrative surrounding him had become.

By the nineteen eighties, pressure to release Hess intensified.

His age and condition made continued imprisonment increasingly indefensible.

It was during this period that he warned his son of impending danger.

His death followed shortly afterward, eliminating the need for any decision about release and ensuring permanent silence.

In 2025, newly authenticated documents brought renewed scrutiny.

These files indicated that Hess’s flight had been anticipated by elements on both sides and that his knowledge remained perceived as a political risk decades after the war.

An intelligence assessment written shortly before his death emphasized the need for absolute containment and warned against exposure.

Shortly thereafter, Hess was gone.

None of this alters the reality of Rudolf Hess’s crimes or ideology.

He was a committed Nazi and a participant in a regime responsible for immense suffering.

Acknowledging suppressed truths does not redeem him.

However, it does challenge the simplicity of the story long presented to the public.

Rudolf Hess was imprisoned not only for what he had done, but for what he knew.

His life demonstrates how governments manage memory, control narratives, and prioritize stability over transparency.

Four nations guarded him.

Forty guards watched him.

Yet when he died, there were no witnesses who could speak freely, no investigation allowed to unfold fully, and no answers that satisfied the evidence.

History recorded a conclusion.

The facts left doubt.

And in that gap between official certainty and unresolved questions, the legacy of Rudolf Hess continues to trouble the record of the twentieth century.

News

JRE: “Scientists Found a 2000 Year Old Letter from Jesus, Its Message Shocked Everyone”

There’s going to be a certain percentage of people right now that have their hackles up because someone might be…

If Only They Know Why The Baby Was Taken By The Mermaid

Long ago, in a peaceful region where land and water shaped the fate of all living beings, the village of…

If Only They Knew Why The Dog Kept Barking At The Coffin

Mingo was a quiet rural town known for its simple beauty and close community ties. Mud brick houses stood in…

What The COPS Found In Tupac’s Garage After His Death SHOCKED Everyone

Nearly three decades after the death of hip hop icon Tupac Shakur, investigators searching a residential property connected to the…

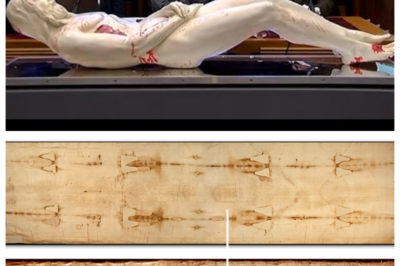

Shroud of Turin Used to Create 3D Copy of Jesus

In early 2018 a group of researchers in Rome presented a striking three dimensional carbon based replica that aimed to…

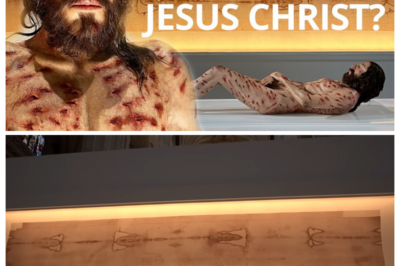

Is this the image of Jesus Christ? The Shroud of Turin brought to life

**The Shroud of Turin: Unveiling the Mystery at the Cathedral of Salamanca** For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has captivated…

End of content

No more pages to load