For centuries, no grave in human history has been protected by silence as fiercely as the tomb of Genghis Khan.

While empires rose and collapsed, while borders shifted and civilizations rewrote themselves, the final resting place of the most formidable conqueror the world has ever known vanished completely from human knowledge.

No marker, no record, no survivor.

It was as if history itself had agreed to forget where the Mongol emperor was laid to rest.

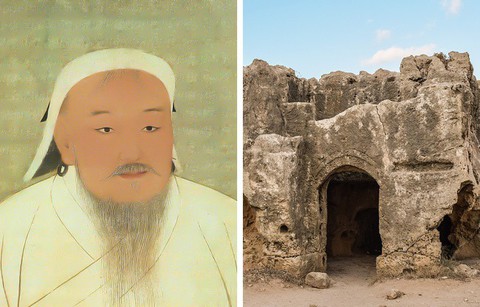

Genghis Khan was not merely a ruler.

He was a force of transformation.

During his lifetime, Mongol armies reshaped Eurasia on an unprecedented scale, conquering vast territories from East Asia to Eastern Europe.

Historians estimate that the wars and conquests associated with his campaigns led to the deaths of tens of millions—so many, in fact, that modern climate researchers suggest the population collapse temporarily altered global carbon levels as farmland reverted to forest.

Few individuals in history have left such a profound biological, political, and cultural footprint.

Yet while his life was marked by thunderous violence and sweeping domination, his death was followed by absolute darkness.

According to Mongol tradition, Genghis Khan demanded that his burial remain secret forever.

His death in 1227 occurred during an active military campaign, and the Mongol leadership feared that revealing it would fracture the empire and embolden their enemies.

Only a small circle of trusted commanders knew the truth.

The army continued marching as if the Khan still lived, while a covert funeral procession carried his body back toward the Mongolian heartland under strict orders of silence.

Legend holds that everyone who witnessed the burial procession was executed.

Those who dug the grave were killed afterward.

Rivers were diverted to wash away tracks.

Thousands of horses were ridden across the land to erase any trace of disturbed soil.

Forests were planted to conceal the site, transforming engineered deception into natural landscape.

Whether every detail of these stories is literal or symbolic, their purpose is unmistakable: the tomb was never meant to be found.

For generations, a vast forbidden zone known as Ikh Khorig—“the Great Taboo”—was sealed off in northern Mongolia.

Only members of the royal Borjigin lineage and selected guardians were allowed inside.

Trespassers faced death.

Oral traditions warned that disturbing the land would bring disaster, not only upon the intruder but upon the nation itself.

Fear, faith, and authority combined to protect the secret across centuries.

Despite this, the mystery only grew stronger.

Modern historians, archaeologists, and explorers became obsessed with the question of where Genghis Khan was buried.

Ancient Persian and Chinese chronicles offered conflicting clues.

Mongolian oral histories pointed vaguely toward the Khentii Mountains, especially the sacred peak Burkhan Khaldun, long associated with the Khan’s life.

But every expedition failed.

Satellite surveys revealed anomalies but no proof.

Ground-penetrating radar detected underground shapes, yet excavation was forbidden out of respect for Mongolian culture.

Then, in recent years, everything changed.

A joint international research effort—operating under unprecedented cooperation between Mongolian authorities, heritage councils, and scientific institutions—began reanalyzing decades of non-invasive data.

Instead of focusing on a single sacred mountain, researchers compared migration routes, seasonal movement patterns, and political geography from the early 13th century.

The conclusion was unsettling: the world may have been searching in the wrong place all along.

A remote region far from traditional search zones showed repeated underground anomalies across multiple independent surveys.

These shapes were not natural.

They appeared geometric, sealed, and deeply buried—consistent with elite burial architecture from the Mongol imperial period.

After years of debate, a tightly controlled excavation was approved under international supervision, with strict cultural and ethical limits.

What the team uncovered stunned even the most cautious experts.

Beneath layers of frozen soil and stone lay a massive sealed chamber, untouched by time.

The construction matched 13th-century Mongol engineering: interlocked stonework designed to withstand pressure, cold, and centuries of isolation.

Inside, the air was still.

Dust lay undisturbed.

Nothing had been looted.

Nothing had collapsed.

The chamber contained ceremonial armor, weapons arranged with deliberate symmetry, bows, blades, and riding equipment bearing unmistakable Mongol craftsmanship.

Scrolls sealed in protective containers remained partially legible.

Clay vessels held preserved food offerings—dried meat and fermented drink—suggesting a burial prepared with both spiritual and practical intention.

Textiles discovered within the tomb revealed the reach of the Mongol Empire at its height.

Silk, wool, and patterned cloth reflected influences from China, Persia, and Central Asia.

These were not random objects; they were symbols of power, conquest, and unity.

At the center lay human remains positioned with extraordinary care.

Preliminary analysis indicated a male consistent in age, stature, and physical profile with historical descriptions of Genghis Khan.

Radiocarbon dating placed the remains firmly in the early 13th century.

DNA testing revealed markers strongly associated with elite Mongol lineages.

While science cannot name the dead with absolute certainty, the convergence of evidence was impossible to ignore.

Personal artifacts deepened the emotional weight of the discovery.

A necklace found near the remains closely resembled one described in Mongol oral tradition as a protective charm from his mother.

Carved tokens near the burial matched designs associated with his first wife, Börte, and a wooden seal bore similarities to imperial insignia used by his son Ögedei.

These objects suggested not only political authority, but family presence—an intimate farewell hidden beneath centuries of silence.

When news of the discovery emerged, the reaction was immediate and divided.

Across Mongolia, pride and fear collided.

Many citizens felt the finding affirmed their national identity and historical legacy.

Others believed a sacred boundary had been violated.

Stories warning of catastrophe resurfaced.

In rural regions, elders questioned whether the tomb should ever have been opened at all.

Beyond Mongolia, geopolitical tension followed.

In Inner Mongolia, ethnic Mongols debated cultural ownership.

Neighboring powers watched closely, aware that history, identity, and influence were suddenly entangled in a single site.

UNESCO urged restraint, emphasizing preservation over spectacle.

The discovery forced the world to confront a deeper question: does uncovering history justify disturbing what was deliberately hidden?

For scientists, the tomb offers an unparalleled window into the Mongol Empire’s inner world.

For historians, it challenges long-standing assumptions.

For Mongolians, it touches the heart of identity, belief, and ancestral respect.

And for the rest of the world, it is a reminder that some truths are buried not because they are lost—but because they were never meant to be found.

Whether the tomb remains open for study or is sealed once more will define how humanity balances knowledge against reverence.

Genghis Khan conquered half the world in life.

In death, he may still be shaping it.

News

3I/ATLAS Just Sent THIS Transmission — And It CONFIRMS Our Worst Fears!

An unidentified object has entered the solar system without warning, without spectacle, and without precedent. There was no brilliant flash…

Archaeologists Just Found Genghis Khan’s Tomb in a Shocking Location

For nearly eight centuries, the burial place of Genghis Khan has remained one of history’s most carefully guarded mysteries. While…

Joe Rogan Reacts to Discovery of Genghis Khan’s Tomb

For centuries, few historical mysteries have stirred as much fascination as the lost tomb of Genghis Khan. The Mongol leader…

What They Found Inside Shocked The World

For seventy-five years, the USS Grayback remained one of World War II’s most haunting naval mysteries. The American submarine vanished…

Buried beneath Centuries of Silence, Secrecy, and Sacred Tradition, an Obscure Historical Account

For centuries, one of the most sacred places in Christianity lay sealed beneath layers of marble, tradition, and silence. Within…

From the Darkest Edge of Interstellar Space, a Faint, Distorted Signal—ignored by many at first—has suddenly ignited intense global speculation, as scientists quietly admit it contains ANOMALIES NEVER RECORDED BEFORE, pushing experts and the public alike to confront one chilling, click-driving question now exploding across search engines: Did Voyager 1’s FINAL TRANSMISSION Just Reveal Something About the Universe That Humanity Was NEVER Meant to Know?

For more than four decades, Voyager 1 had existed only as a fading artifact of human ambition, a silent envoy…

End of content

No more pages to load