Deep beneath the quiet forests and alpine landscapes of southern Germany, a hidden chapter of World War II history has emerged—one that forces historians to confront the scale, secrecy, and long-term ambitions of the Nazi regime.

The recent discovery of a long-sealed underground complex in Bavaria has reignited global interest in the subterranean world built by Adolf Hitler and his inner circle, revealing not just bunkers designed for wartime survival, but an extensive underground strategy intended to preserve power, resources, and secrets far beyond the war’s end.

The discovery occurred by chance during routine renovation work at a decades-old mountainside hotel in the Bavarian Alps.

Construction crews excavating beneath the foundation uncovered an unusual concrete structure that did not appear on any architectural plans.

Further investigation revealed a sealed metal hatch leading deep underground.

When authorities were alerted and specialists carefully opened the entrance, they descended into a network of reinforced tunnels and chambers that had remained untouched since the collapse of the Third Reich in 1945.

What they found was not a simple bomb shelter.

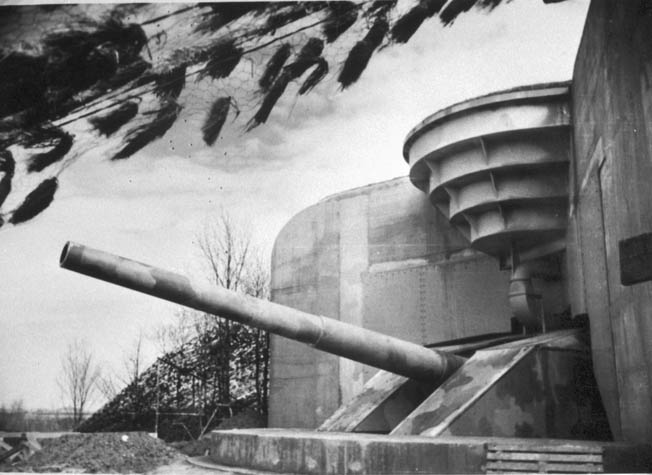

The underground facility was expansive, meticulously engineered, and clearly designed for prolonged habitation.

Narrow corridors led to living quarters furnished with metal beds, desks, storage rooms, and communication equipment.

Thick concrete walls suggested the complex was built to withstand sustained bombardment.

Air filtration systems, power conduits, and water access indicated that those who constructed it anticipated extended isolation from the outside world.

Among the most unsettling discoveries was a fully intact residential section, including a bathroom with a porcelain bathtub—an unusual luxury for a wartime bunker.

Historians noted that such details pointed to the presence of high-ranking occupants rather than ordinary soldiers.

A large, fortified chamber near the center of the complex appeared to function as a command or planning room, featuring reinforced doors and structural enhancements not found elsewhere in the site.

The layout suggested that the facility may have been intended as a contingency headquarters or emergency refuge for senior Nazi leadership.

What makes the discovery particularly striking is the absence of any official documentation referencing the bunker.

No construction records, military maps, or postwar Allied reports mention its existence.

This omission supports long-standing suspicions that many Nazi underground projects were deliberately excluded from official archives, built in secrecy by forced labor and concealed even from lower-ranking officials.

The Bavarian site now joins a growing list of clandestine facilities uncovered across Europe decades after the war.

The discovery has also renewed interest in the broader network of underground infrastructure developed by the Nazis during the later years of World War II.

As Allied bombing intensified and the prospect of defeat became increasingly likely, Hitler ordered the expansion of fortified subterranean complexes throughout Germany and occupied territories.

These sites served multiple purposes: command centers, weapons factories, storage vaults, and potential escape routes.

One of the most well-known examples is the Wolf’s Lair in present-day Poland, where Hitler directed military operations and narrowly survived an assassination attempt in 1944.

Less understood, however, are massive unfinished projects such as Project Riese in the Owl Mountains, a vast tunnel system whose intended function remains disputed.

Some scholars believe it was designed as an underground headquarters; others argue it may have been intended for weapons development or industrial production shielded from air raids.

The newly discovered Bavarian complex shares architectural similarities with these sites, particularly in its emphasis on concealment, redundancy, and durability.

Engineers involved in examining the structure noted that the tunnel system included multiple branching routes leading to discreet exit points concealed beneath forest floors, abandoned buildings, and even old railway lines.

These features suggest the bunker was designed not only for protection, but also for escape and erasure—allowing occupants to disappear without leaving a trace.

As investigators explored deeper sections of the complex, they uncovered sealed chambers and vault-like rooms reinforced with steel plating.

Within these spaces, archaeologists found damaged documents, coded notebooks, and fragments of machinery that have yet to be fully identified.

Some of the materials appear consistent with experimental research equipment from the late war period, though experts caution against speculation until comprehensive analysis is complete.

The discovery inevitably revives questions surrounding the Nazis’ obsession with secrecy, advanced technology, and long-term survival strategies.

While popular culture has often exaggerated claims of hidden superweapons or occult experiments, historians agree that the regime invested heavily in underground research facilities, particularly as surface-level factories became vulnerable to destruction.

The extent of these efforts—and how many such sites remain undiscovered—remains an open question.

Parallel to the uncovering of physical infrastructure is the unresolved legacy of Nazi art theft, one of the most systematic cultural crimes in history.

From the moment Hitler rose to power in 1933, the Nazi regime targeted Jewish families and occupied nations not only through violence and displacement, but through the deliberate seizure of cultural property.

Paintings, sculptures, manuscripts, religious artifacts, and personal heirlooms were confiscated on a massive scale, stripped from homes and institutions across Europe.

Much of this stolen property was hidden in underground locations similar to the Bavarian bunker.

Salt mines, mountain vaults, and concealed bunkers were used to store looted art and valuables intended for private collections or Hitler’s planned museum in Linz, Austria.

While Allied recovery teams known as the Monuments Men succeeded in locating and returning thousands of works after the war, countless items remain missing or trapped in unresolved legal disputes.

The rediscovery of underground Nazi facilities raises the possibility that additional caches of stolen art or documents may still be hidden beneath Europe’s landscapes.

In recent years, renewed investigations have followed tips, archival anomalies, and advanced ground-scanning technologies in search of lost treasures—including the persistent legend of a Nazi gold train rumored to be buried in Poland.

While many such claims remain unproven, occasional discoveries continue to demonstrate that not all wartime secrets were unearthed in the immediate aftermath of 1945.

German authorities have emphasized that the Bavarian site is being handled with extreme care.

Access is restricted to qualified personnel, and the investigation is being conducted in cooperation with international historians, engineers, and forensic experts.

Officials stress that the goal is not sensationalism, but historical clarity—understanding how such a complex could be built, hidden, and forgotten for so long.

For scholars, the bunker represents more than a physical structure; it is evidence of a regime that planned for survival even in defeat.

The Nazis did not simply fight a conventional war—they prepared for a world in which they might operate from the shadows, protected by stone, steel, and secrecy.

These underground spaces reflect a mindset rooted in paranoia, control, and an unwillingness to accept the finality of loss.

The discovery also challenges assumptions about the completeness of historical records.

Despite decades of research, trials, and documentation, the physical remnants of the Third Reich continue to surface in unexpected ways.

Each bunker, tunnel, or hidden chamber forces historians to reassess what is known—and what may still be missing.

As excavation and analysis continue, experts caution against drawing premature conclusions.

There is no evidence that the Bavarian complex was ever occupied by Hitler himself, nor that it housed advanced weapons or postwar operations.

What is clear, however, is that it formed part of a broader strategy of concealment and endurance that extended far beyond conventional military planning.

The quiet forests of Bavaria now sit atop a reminder that history does not always remain buried.

Beneath peaceful landscapes can lie structures built for fear, domination, and survival at any cost.

As long as such sites continue to emerge, the legacy of World War II remains unfinished—not as a matter of mythology, but as an ongoing process of discovery, accountability, and understanding.

In uncovering these forgotten spaces, the world is reminded that the past is not static.

It waits—sometimes silently, sometimes buried deep underground—until the moment it resurfaces, demanding to be examined once more.

News

Steven Spielberg Reveals the Side of Rob Reiner No One Talks About

The Unseen Side of Rob Reiner: A Tribute by Steven Spielberg In a heartfelt tribute, acclaimed filmmaker Steven Spielberg shares…

Rob Reiner’s $200M Fortune SHOCKER..

The Controversy Surrounding Rob Reiner’s $200 Million Fortune: A Closer Look Recent reports have stirred considerable excitement and debate in…

What the Data, the Audio, and the NTSB Aren’t Saying about the Greg Biffle crash

In the days following the fatal crash of a Cessna Citation II near Statesville, North Carolina, the absence of clear…

The Sentence That Made Recovery IMPOSSIBLE in the Greg Biffle Crash

A single sentence can sound ordinary, even reassuring, while quietly revealing that a decisive boundary has already been crossed. In…

Bob Lazar and Steven Greer Released Huge Update on Mysterious Alien Sphere!

A mysterious metallic sphere discovered in Colombia has rapidly evolved from a local curiosity into one of the most controversial…

AI Found Something Impossible in the Shroud of Turin — Scientists Are Terrified to Explain

For as long as the Shroud of Turin has been known to the modern world, it has carried controversy in…

End of content

No more pages to load