The Greg Biffle Jet Tragedy: A Veteran Pilot’s Warning and the Rules Written in Blood

In the days following the aviation tragedy involving NASCAR legend Greg Biffle, the aviation community has been flooded with questions.

Was the cause mechanical failure, pilot error, or the unavoidable risks of operating an aging aircraft? While investigators from the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) continue their work and the official report remains pending, a new and sobering analysis has emerged from a highly respected source: a veteran Citation jet captain with more than four decades of experience flying the same aircraft type.

Captain Glen, a retired Citation II pilot with over 40 years in business aviation, has stepped forward not to speculate recklessly, but to issue a warning.

His analysis points to a seemingly insignificant detail that could have triggered a catastrophic chain of events—the nose baggage door.

More importantly, his insights expose deeper systemic problems that persist in private aviation: shortcuts in training, compromises in maintenance, and routine dishonesty about weight and performance limitations.

According to Captain Glen, aviation disasters are rarely the result of a single failure.

They are the outcome of multiple small breakdowns aligning in what safety experts refer to as the “Swiss Cheese Model.

” When those layers of defense fail simultaneously, tragedy becomes inevitable.

The Baggage Door Scenario

At the center of Glen’s analysis is the Citation II’s forward baggage compartment, located directly in the aircraft’s nose, ahead of the cockpit windshield.

Secured by two mechanical latches and a key lock, the door appears unremarkable to an untrained observer.

Aerodynamically, however, it is a critical structural component.

The scenario begins on the ground.

During pre-flight preparations, the pilot is often managing fuel calculations, weather briefings, clearances, and systems checks.

In many owner-operated aircraft, the owner or a passenger may offer to help by loading baggage and closing the door.

If the pilot accepts that assistance without personally verifying the latches, the first breach in safety occurs.

In aviation, Captain Glen emphasizes, there is no such thing as shared responsibility for critical items.

The baggage door is the captain’s territory—always.

As the aircraft accelerates during takeoff, aerodynamic pressure builds rapidly.

At speeds approaching 180 knots, even a slightly misaligned latch can fail.

When it does, the result is violent.

The door may burst open or tear away entirely, creating an explosive rush of air into the cockpit.

Communication becomes nearly impossible as wind noise overwhelms headsets.

The danger does not end there.

Loose baggage—or fragments of the door itself—can be sucked into the airflow along the fuselage.

On a Citation II, that airflow travels directly toward the rear-mounted engines.

This introduces the risk of foreign object damage (FOD), potentially leading to catastrophic engine failure at the worst possible moment: immediately after takeoff.

While investigators have confirmed that the baggage door was damaged at the crash site, it remains unclear whether the failure occurred before or after impact.

Nevertheless, Glen’s warning is stark.

Trusting someone else to secure a critical aircraft component can have fatal consequences.

The Myth of the “Old Jet”

Public discussion following the crash has raised concerns about the age of the aircraft.

Captain Glen rejects the assumption that older jets are inherently unsafe.

The Citation II, he explains, is a robust and durable aircraft, often described as “a tank.

” The real issue is not age, but workload.

Unlike modern business jets equipped with advanced flight management systems (FMS), the Citation II’s cockpit is largely analog.

There is no onboard computer calculating takeoff speeds, runway margins, or weight and balance in real time.

Those calculations must be done manually by the pilot.

In normal conditions, a proficient single pilot can manage this workload.

In an emergency, the demands increase exponentially.

An engine failure during takeoff requires immediate and precise action: maintaining control, identifying the failed engine, correcting yaw, managing airspeed, communicating with air traffic control, and configuring the aircraft correctly—all without digital assistance.

This phenomenon is known as “task saturation.

” When cognitive demand exceeds capacity, even experienced pilots can freeze or miss critical steps.

Glen’s assessment is blunt: operating a high-workload vintage jet requires a highly experienced pilot.

Attempting to save money by pairing a complex aircraft with a low-time pilot is a recipe for disaster.

“If you buy a cheap jet,” Glen warns, “you need an expensive pilot.

Training and the “Boxed Items”

Central to pilot survival in emergencies are procedures known as “memory items,” often displayed in bold or boxed text in aircraft manuals.

These are immediate-action steps designed for situations where there is no time to consult a checklist.

Examples include engine fire responses, loss of thrust, or uncommanded system deployments.

These procedures must be executed from memory, instantly and correctly.

Hesitation can be fatal.

Captain Glen highlights a critical divide in pilot training standards.

On one end are elite training organizations, such as FlightSafety International, where pilots undergo weeks of intensive simulator training.

These programs expose pilots to repeated emergency scenarios until responses become instinctive.

On the other end are minimal training operations, sometimes offering type ratings with limited simulator exposure or abbreviated check rides.

While legal, such training may leave pilots unprepared for high-stress emergencies.

The suspected hesitation observed in the Biffle crash—sometimes referred to as the “startle factor”—raises questions about whether the pilot’s training adequately prepared him for a sudden cascade of failures.

In aviation, Glen argues, training quality is not a luxury.

It is a survival requirement.

The Weight Lie

One of the most dangerous habits in private aviation, according to Captain Glen, is the routine underreporting of weight.

Passengers may underestimate their own weight.

Owners may pressure pilots to load full fuel and baggage to avoid inconvenient fuel stops.

Physics, however, is unforgiving.

The Citation II has strict limits for maximum takeoff weight and center of gravity (CG).

Exceeding those limits degrades performance dramatically.

Excess weight increases takeoff distance and reduces climb rate.

Improper CG—particularly when too much weight is stored in aft baggage compartments—makes the aircraft unstable.

A nose-light aircraft has a natural tendency to pitch up during takeoff.

If pitch exceeds critical angles, the wings can stall.

At low altitude, stall recovery is impossible.

Glen emphasizes that even small discrepancies matter.

Thirty pounds may seem trivial, but when placed far from the aircraft’s center of gravity, it creates a destabilizing moment large enough to compromise safety.

A prudent pilot, Glen argues, would accept a fuel stop rather than attempt to stretch range limits.

“Arriving late is better than not arriving at all,” he says.

The Dirty Configuration Trap

Witness reports suggest the aircraft may have been maneuvering after takeoff, possibly attempting to return to the airport.

Glen suspects the aircraft may have been in a “dirty configuration,” meaning landing gear and flaps remained extended.

On a single engine, this configuration is deadly.

Extended gear and flaps create enormous drag, reducing climb performance to near zero.

In a turn, the situation worsens, as bank angle increases the aircraft’s effective weight.

In modern jets, automated systems assist pilots during go-arounds.

In older aircraft like the Citation II, the pilot must manage energy manually.

Forgetting to retract the landing gear—a simple step known as “positive rate, gear up”—can mean the difference between survival and impact.

Under stress, even simple steps can be missed.

Maintenance and Logbook Forensics

Beyond pilot actions, Glen stresses the importance of maintenance pedigree.

Buying a used jet means inheriting the habits of previous owners and mechanics.

He distinguishes between generalist mechanics and specialists.

A certified Cessna service center technician has likely serviced hundreds of Citation aircraft and understands their recurring failure points.

A general aviation mechanic may not.

In the case of the baggage door, proper latch adjustment requires specific knowledge and experience.

“Tight enough” is not an acceptable standard in aviation.

The NTSB will scrutinize maintenance records to determine who last serviced the door and whether they were qualified to do so.

Rules Written in Blood

As investigators continue their work, Captain Glen’s analysis offers lessons for owners, pilots, and passengers alike.

These lessons, he says, are not theoretical.

They are written in blood.

The captain alone is responsible for critical aircraft components.

Older jets demand higher pilot experience, not lower budgets.

Memory items must be trained relentlessly.

Weight and balance must be honest and precise.

Maintenance pedigree matters as much as the aircraft itself.

Greg Biffle was a champion on the racetrack.

In the sky, however, no one outruns physics.

Until the final report is released, these lessons stand as a legacy—warnings that may prevent the next tragedy.

News

Girl In Torn Clothes Went To The Bank To Check Account, Manager Laughed Until He Saw The Balance What If Appearances Lied So Completely That One Look Cost Someone Their Dignity—and Another Person Their Job? What began as quiet ridicule quickly turned into stunned silence when a single number appeared on the screen, forcing everyone in the room to confront their assumptions. Click the article link in the comment to see what happened next.

Some people only respect you when they think you’re rich. And that right there is the sickness. This story will…

Billionaire Goes Undercover In His Own Restaurant, Then A Waitress Slips Him A Note That Shocked Him

Jason Okapor stood by the tall glass window of his penthouse, looking down at Logos. The city was alive as…

Billionaire Heiress Took A Homeless Man To Her Ex-Fiancé’s Wedding, What He Did Shocked Everyone

Her ex invited her to his wedding to humiliate her. So, she showed up with a homeless man. Everyone laughed…

Bride Was Abandoned At The Alter Until A Poor Church Beggar Proposed To Her

Ruth Aoy stood behind the big wooden doors of New Hope Baptist Church, holding her bouquet so tight her fingers…

R. Kelly Victim Who Survived Abuse as Teen Breaks Her Silence

The early 2000s marked a defining moment in popular culture, media, and public conversation around fame, power, and accountability. One…

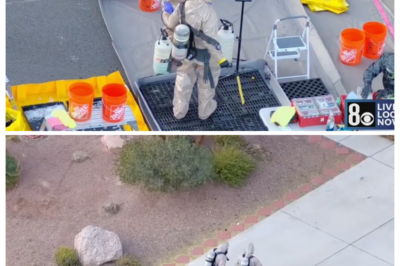

Las Vegas Bio Lab Sparks Information Sharing, Federal Oversight Concerns: ‘I’m Disappointed’

New questions are emerging over why a suspected illegal biolab operating from a residential home in the East Valley appeared…

End of content

No more pages to load