The pyramids of Egypt have long fascinated humanity, symbolizing both the ingenuity and mystery of ancient civilizations.

For generations, students have been taught that these colossal structures were built as tombs for pharaohs, constructed with simple copper tools and enormous amounts of human labor.

According to the mainstream account, tens of thousands of workers toiled for decades to erect the Great Pyramid of Giza under the reign of Pharaoh Khufu around 2560 BCE.

The official narrative presents a story of extraordinary human achievement, but it remains within the bounds of what a determined Bronze Age society could accomplish.

Yet some researchers and writers have challenged this explanation, proposing that the true origins of the pyramids may lie far beyond conventional understanding.

One of the most prominent voices in this debate is Graham Hancock, a British journalist who has spent decades investigating ancient mysteries, challenging accepted historical timelines, and questioning the foundations of modern archaeology.

Graham Hancock is not a traditional academic.

His career began in journalism, writing for respected outlets such as The Economist and The Times, covering current affairs and international politics.

In the 1990s, he shifted his focus toward the study of ancient civilizations and lost knowledge.

His first major work, Fingerprints of the Gods, published in 1995, presented the controversial idea that an advanced civilization existed long before the historically recognized cultures of Mesopotamia and Egypt.

According to Hancock, this civilization was destroyed by a cataclysm, but fragments of its knowledge survived, influencing later societies.

The pyramids, he argues, are part of this inheritance, monuments built not by the pharaohs of the Old Kingdom, but by a civilization whose achievements far surpass what mainstream history credits to ancient humans.

Hancock’s work challenges the widely accepted story of pyramid construction.

The Great Pyramid of Giza is composed of approximately 2.

3 million limestone and granite blocks, some weighing more than eighty tons.

Many of the granite blocks were transported from quarries over five hundred miles away in Aswan.

Mainstream archaeology maintains that these massive stones were moved using sledges, rollers, ropes, and sheer manpower.

Hancock questions this explanation, suggesting that it strains credibility.

The scale of the work, the precision required, and the absence of detailed construction plans or architectural diagrams make the official story seem improbable.

For Hancock, it is not a question of doubting the ingenuity of the Egyptians, but of highlighting inconsistencies and unanswered questions that conventional narratives leave unresolved.

Time is another critical factor in Hancock’s critique.

The construction of the Great Pyramid is believed to have taken around twenty years.

This timeframe would require placing blocks at a rate of every two to three minutes, day and night, without interruption or error.

The logistical challenges of such an endeavor, combined with the technological limitations of the time, raise questions about whether the official story is realistic.

Hancock emphasizes that there is no evidence of architectural blueprints, construction plans, or instructions preserved from that period.

Ancient Egyptians produced detailed records for taxes, grain distribution, and religious rituals, yet nothing exists to explain how the pyramids were built.

The absence of these records, Hancock suggests, is a significant clue pointing to an alternative history.

The tools attributed to pyramid construction also pose a problem.

According to mainstream theory, the Egyptians used copper chisels to cut and shape granite, one of the hardest materials on Earth.

Hancock and other skeptics argue that this explanation is insufficient.

Modern stonemasons, using diamond-tipped equipment, still face challenges in achieving the level of precision evident in the pyramid’s internal chambers.

The smooth surfaces, exact angles, and seamless joints indicate knowledge of engineering and techniques far beyond what copper chisels could achieve.

These anomalies fuel Hancock’s belief that conventional explanations fail to account for the sophistication of the structures.

Another point of interest is the interior of the Great Pyramid itself.

Unlike other tombs from the Old Kingdom, which were richly decorated with hieroglyphics, artwork, and elaborate carvings, the Great Pyramid’s chambers are stark and undecorated.

Hancock views this as unusual, suggesting that a structure intended as a royal tomb would typically celebrate its occupant.

The silence of the pyramid’s walls, combined with the precision of its construction and its exact alignment with true north, supports his theory that the pyramids are part of a much older architectural tradition.

The alignment is remarkable, with a deviation of only a fraction of a degree, surpassing even some modern engineering achievements.

Hancock interprets this as evidence of advanced knowledge, possibly inherited from a civilization far older than the Old Kingdom.

Hancock’s argument extends beyond Egypt.

He proposes that the pyramids may be far older than traditionally believed.

Geologist Robert Schoch, whose work Hancock cites extensively, analyzed erosion patterns on the Great Sphinx and concluded that the type of vertical water erosion visible on the statue could have occurred only during a period of heavy rainfall, likely before 10,000 BCE.

This predates the established timeline of Egyptian civilization and suggests that the Giza Plateau may contain monuments from a lost epoch.

Hancock argues that the Old Kingdom pharaohs may have inherited these structures, later adding finishing touches and claiming credit for construction.

This perspective aligns with historical patterns in which Egyptian rulers renovated and repurposed older temples, potentially preserving but obscuring their original origins.

Astronomical evidence further supports Hancock’s theory.

The three pyramids of Giza mirror the stars in Orion’s Belt, which held significant mythological importance for ancient Egyptians.

The alignment is most accurate not for 2560 BCE, when the pyramids were supposedly built, but for around 10,500 BCE.

This correlation, known as the Orion Correlation Theory, suggests that the monuments were constructed to reflect the stars at a time long before the official emergence of Egyptian civilization.

Hancock extends this reasoning globally, noting that similar alignments and advanced astronomical knowledge appear at ancient sites such as Stonehenge and Angkor Wat.

He interprets these patterns as remnants of a sophisticated, prehistorical understanding of the heavens, encoded into monumental architecture.

The discovery of Göbekli Tepe in modern Turkey adds another dimension to Hancock’s argument.

This site, dated to at least 9600 BCE, is the oldest known megalithic complex in the world, predating Stonehenge and the Egyptian pyramids.

Its massive carved stone pillars, intricate symbols, and precise astronomical alignments challenge the conventional view that complex societies arose only after the advent of agriculture.

Göbekli Tepe suggests that humans in deep prehistory were capable of monumental construction and advanced intellectual organization.

Hancock uses this evidence to argue that other ancient structures, including the pyramids, may similarly originate from civilizations that have been lost to history.

Hancock also considers catastrophic events in shaping human history.

He cites the Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis, which posits that Earth was struck by fragments of a comet around 12,800 years ago.

This event caused rapid climate change, massive flooding, and the potential collapse of early advanced societies.

If such civilizations existed, Hancock suggests, the evidence of their achievements would have been largely destroyed, leaving only durable monuments like the pyramids as remnants of their knowledge.

This theory challenges the linear narrative of human history, proposing a cyclical pattern in which civilizations rise, fall, and contribute fragments to future generations.

The technological sophistication of ancient structures remains a central question.

Hancock notes that the precision stonework found in Egypt, Peru, and other locations demonstrates knowledge that modern technology struggles to replicate.

Massive stones are cut with extreme accuracy and fit together without mortar.

Complex engineering techniques, including shock-absorbing designs and interlocking blocks, suggest that ancient builders possessed skills and knowledge that have been lost or forgotten.

The widespread presence of similar techniques across disparate regions supports the idea of a shared technological legacy from a previous civilization.

Hancock contends that while parallel development is theoretically possible, the consistency and precision of these constructions imply the influence of a preexisting knowledge network.

Hancock supports his claims with diverse evidence.

Advances in technology, such as lidar and ground-penetrating radar, have revealed buried structures and anomalies beneath known archaeological sites.

Underwater discoveries, such as the Yonaguni complex in Japan and the Bimini Road in the Bahamas, suggest the existence of submerged cities and structures from the last Ice Age.

Ancient maps, including the Piri Reis map, depict coastlines as they existed thousands of years earlier, raising questions about lost cartographic knowledge.

Artifacts like the Baghdad Battery and the Antikythera Mechanism further illustrate the potential sophistication of ancient technology.

Hancock interprets these findings as indicators of a global civilization that predates recorded history and possessed advanced engineering, astronomical, and technological capabilities.

Hancock’s work has generated significant controversy.

The academic establishment is highly resistant to his theories, largely due to the perceived threat to established narratives and the rigid structures of scientific and historical research.

Archaeology is a field governed by tenure, funding, and peer-reviewed publication, and deviation from accepted paradigms can result in professional isolation.

Hancock’s approach, which reaches directly to the public through books and documentaries, bypasses traditional academic channels, further antagonizing mainstream scholars.

Critics accuse him of promoting pseudoscience, while supporters argue that he is asking valid questions and presenting evidence that deserves attention.

The resistance to Hancock’s work also reflects a broader psychological and cultural preference for neat historical narratives.

Conventional history presents a linear story of human development from Mesopotamia and Egypt to Greece, Rome, and modern societies.

Acknowledging the possibility of an earlier, sophisticated civilization complicates this narrative, introducing uncertainty and the need to reevaluate long-held assumptions.

Hancock challenges both scholars and the public to consider a more complex and mysterious past, one in which human civilization has risen, fallen, and been reshaped over millennia.

Ultimately, Hancock’s research emphasizes curiosity and the pursuit of knowledge.

His work does not claim absolute certainty but highlights anomalies, questions, and evidence that conventional archaeology often overlooks.

Whether one accepts his conclusions or not, his exploration of ancient mysteries encourages a reexamination of history and the recognition that human achievement may be far older and more sophisticated than previously believed.

The pyramids, the Sphinx, Göbekli Tepe, and other ancient structures may be far more than tourist attractions or royal tombs.

They may be enduring messages from civilizations lost to time, waiting to be understood and decoded.

Hancock’s contributions underscore the importance of remaining open to new ideas in the study of human history.

The pyramids challenge assumptions, stimulate debate, and remind humanity that the past is a dynamic, evolving story.

His work suggests that mysteries remain, waiting to be unraveled, and that the search for understanding is ongoing.

The conversation about who built the pyramids, how they achieved such remarkable feats, and what knowledge has been lost continues to inspire curiosity, research, and wonder.

Graham Hancock has positioned himself at the forefront of this debate, encouraging a deeper look into the enigmatic achievements of humanity’s distant past and urging society to reconsider the possibilities of lost civilizations, advanced ancient technologies, and the cyclical nature of history.

The pyramids remain silent yet profound, their lessons hidden within the stones, ready for those willing to ask questions and seek answers.

News

JRE: “Scientists Found a 2000 Year Old Letter from Jesus, Its Message Shocked Everyone”

There’s going to be a certain percentage of people right now that have their hackles up because someone might be…

If Only They Know Why The Baby Was Taken By The Mermaid

Long ago, in a peaceful region where land and water shaped the fate of all living beings, the village of…

If Only They Knew Why The Dog Kept Barking At The Coffin

Mingo was a quiet rural town known for its simple beauty and close community ties. Mud brick houses stood in…

What The COPS Found In Tupac’s Garage After His Death SHOCKED Everyone

Nearly three decades after the death of hip hop icon Tupac Shakur, investigators searching a residential property connected to the…

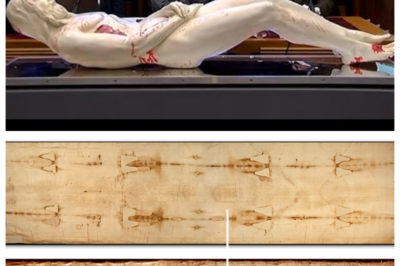

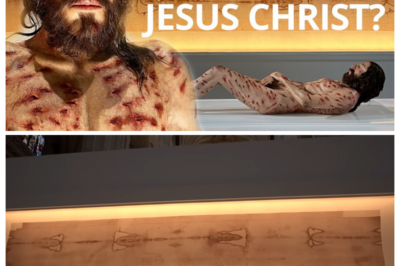

Shroud of Turin Used to Create 3D Copy of Jesus

In early 2018 a group of researchers in Rome presented a striking three dimensional carbon based replica that aimed to…

Is this the image of Jesus Christ? The Shroud of Turin brought to life

**The Shroud of Turin: Unveiling the Mystery at the Cathedral of Salamanca** For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has captivated…

End of content

No more pages to load