As devoted Dead Heads gathered outside San Francisco’s historic Fillmore Theater, anticipation filled the air for the opening night of Dead and Company’s summer tour.

The band represented a continuation of a musical legacy that began more than half a century earlier.

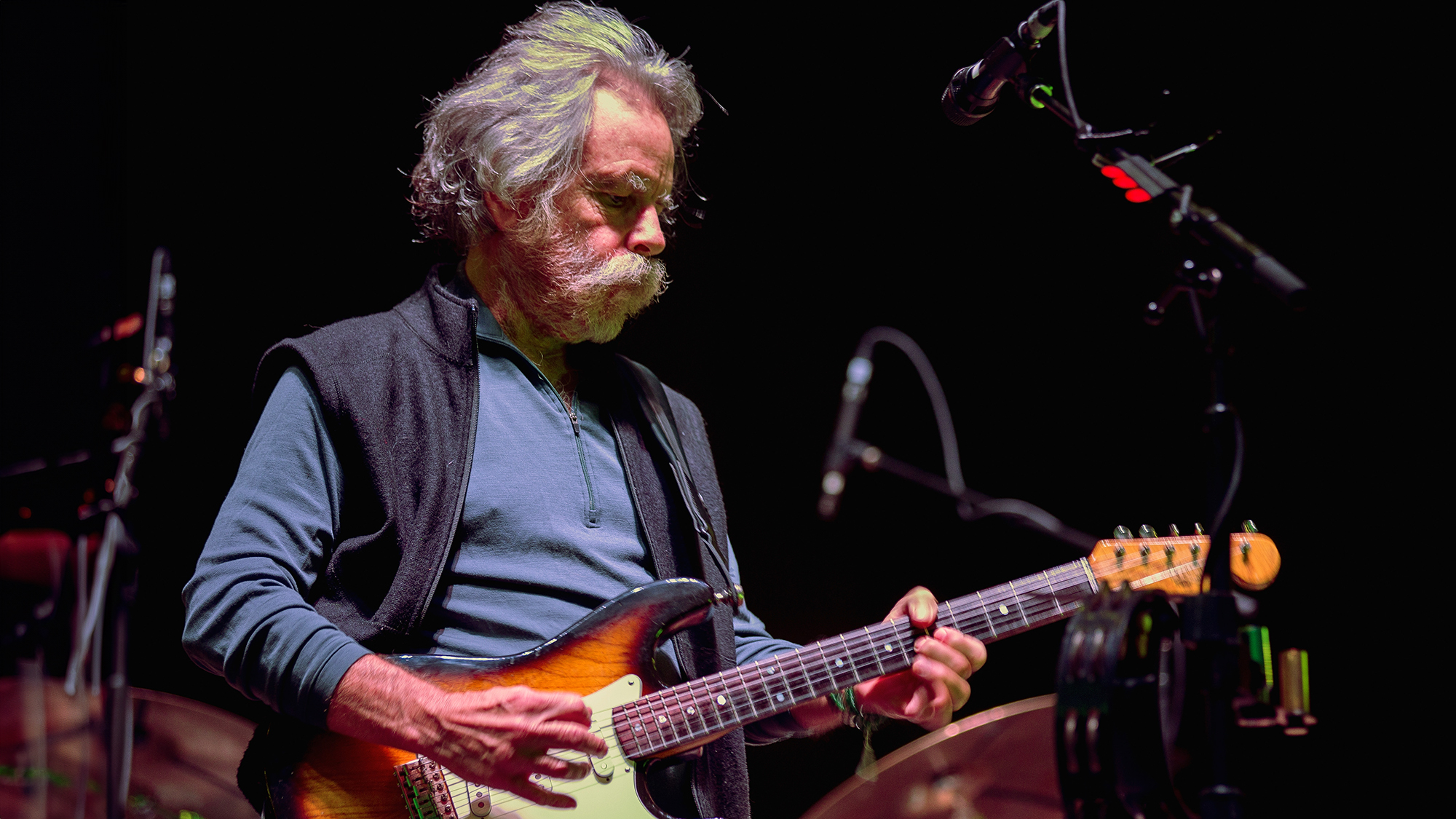

Dead and Company featured three surviving core members of the Grateful Dead, drummer Mickey Hart, drummer Bill Kreutzmann, and guitarist Bob Weir, joined by guitarist John Mayer, keyboardist Jeff Chimenti, and bassist Oteil Burbridge.

While the lineup reflected generational change, the music remained rooted in the enduring Grateful Dead catalog that had shaped American musical culture.

The Fillmore Theater held deep significance for the band.

More than fifty years earlier, it had been the first major venue the Grateful Dead ever played, marking a turning point in their evolution from a local experimental group into a defining force of the counterculture movement.

Posters from early performances lined the walls, including one of the first shows promoter Bill Graham ever booked there in nineteen sixty six.

At that time, the band had recently changed its name from the Warlocks to the Grateful Dead, beginning a relationship with the Fillmore that would become legendary.

For Bob Weir, returning to the Fillmore felt like coming home.

The theater stood as a physical archive of shared memory, creativity, and transformation.

A large photograph of the late Jerry Garcia, who died in nineteen ninety five, hung in the stairwell, serving as a silent reminder of the partnership that defined much of Weir’s life.

Garcia and Weir shared a bond built on mutual curiosity and constant exchange, whether musical, intellectual, or personal.

Their connection formed the emotional core of the Grateful Dead’s sound and philosophy.

Bob Weir joined the Grateful Dead at just sixteen years old.

Drummer Bill Kreutzmann was eighteen, and Mickey Hart joined soon after.

What began as an informal collaboration quickly became something singular.

In nineteen sixty six, the band moved into a communal house in the Haight Ashbury district, where creativity and chaos coexisted.

The house became a symbol of the era, later immortalized during the Summer of Love when a national television network documented the group’s unconventional lifestyle.

That same year, the house was raided by police, highlighting the tension between the emerging counterculture and established authority.

Despite controversy, the Grateful Dead grew into a touring powerhouse.

Their performances emphasized improvisation, spontaneity, and connection with audiences, attracting a devoted following known as Dead Heads.

These fans traveled from city to city, forming a community built around shared experience rather than commercial spectacle.

The band’s concerts were never the same twice, and this unpredictability became a defining trait.

Decades later, that philosophy continued through Dead and Company.

While some expected the music to conclude after the Grateful Dead’s fiftieth anniversary Fare Thee Well concerts, Weir chose to continue.

Rather than retreat into retirement, he embraced reinvention.

Dead and Company represented not nostalgia but evolution, allowing the music to breathe through new voices while honoring its roots.

John Mayer emerged as a surprising yet natural collaborator.

Though known for a successful solo career, Mayer approached the Grateful Dead repertoire with humility and discipline.

He immersed himself in the music, studying its structure, style, and emotional depth.

His dedication earned the respect of both bandmates and longtime fans.

Mayer temporarily set aside his solo ambitions to fully commit to the project, living near Weir’s studio during rehearsals to remain immersed in the creative process.

Weir viewed the band not as a finished product but as a living organism.

He described their music as a continuous process of revolution rather than repetition.

Each performance required musicians to listen closely, respond instinctively, and navigate a complex interplay of rhythm, harmony, and space.

Mastery did not come from technical precision alone but from the ability to remain present and adaptive.

Improvisation remained central.

Unlike bands that replicate recordings, the Grateful Dead tradition demanded interpretation and reinvention.

Songs evolved over time, shaped by the musicians performing them and the energy exchanged with the audience.

Weir believed that the music existed in the space between stage and crowd, a shared creation rather than a fixed composition.

Beyond Dead and Company, Weir pursued ambitious collaborations that expanded the Grateful Dead repertoire into new realms.

One of the most significant involved orchestral arrangements performed with his band Wolf Bros alongside major symphony orchestras.

These projects reimagined Grateful Dead songs through classical instrumentation, revealing their structural depth and harmonic complexity.

Preparing for these performances required discipline and adaptation.

Unlike the loose structure of jam bands, orchestral settings demanded precision and written scores.

Weir, who does not read music due to severe dyslexia, committed the arrangements entirely to memory.

He absorbed the music through repetition and feeling, internalizing each section until it became instinctive.

This process reflected his lifelong approach to learning, relying on intuition and embodiment rather than formal notation.

The orchestral collaborations demonstrated that the Grateful Dead’s music possessed a timeless quality capable of transcending genre.

Academic composers studying the material noted its sophisticated counterpoint, rhythmic layering, and harmonic innovation.

What began as folk rooted improvisation proved adaptable to the most formal musical traditions.

Weir’s motivation to continue working at an advanced age stemmed from devotion rather than obligation.

Music remained his guiding force, providing purpose and direction.

He maintained physical fitness to support the demands of touring and performance, sharing workouts and routines that kept him prepared for the road.

Despite the challenges of travel, he believed bringing music directly to audiences mattered more than convenience.

Commercial success followed naturally.

Dead and Company ranked among the highest grossing tours worldwide, demonstrating sustained relevance across generations.

Yet Weir measured success not in numbers but in connection.

He valued moments when listeners expressed gratitude for shared experiences rather than admiration for individual performance.

Stage fright never fully disappeared.

Weir described it as a permanent companion that required acknowledgment rather than elimination.

Once the music began, energy from the audience carried him forward, dissolving anxiety into focus.

The exchange between performers and listeners remained the essence of live music.

Looking toward the future, Weir thought beyond immediate impact.

He considered how the music might be perceived centuries from now.

His decisions increasingly reflected a long view, guided by the belief that artistic integrity could ensure longevity.

He aimed to contribute something enduring, something that future generations might still find meaningful.

For Bob Weir, the Grateful Dead was never merely a band.

It was an idiom, a musical language with its own grammar and tradition.

Learning its songs required understanding its style, and mastering that style opened pathways to broader musical fluency.

The legacy continued not through imitation but through participation.

As the music evolved through new collaborations, orchestral interpretations, and generational exchange, Weir remained at its center, not as a gatekeeper but as a steward.

His life’s work reflected curiosity, humility, and commitment.

The long strange trip continued, shaped by time, memory, and the shared belief that music, when treated as a living force, could outlast those who created it.

News

Pope Leo XIV Paused 6 Second READING THIRD SECRET..

REVEALS SHOCKING TRUTH ON ORTHODOX CARDINAL BURKE

On November 27, 2025, a moment of silence inside the Vatican set in motion one of the most consequential theological…

Bob Weir’s final performance “Touch of Grey” with Dead & Company 08/03/25 San Francisco, CA

Remembering Bob Weir: A Tribute to His Final Performance Bob Weir, the legendary guitarist and co-founder of the Grateful Dead,…

Bob Weir’s final performance “Touch of Grey” with Dead & Company 08/03/25 San Francisco, CA

Archaeology has entered an era in which long accepted narratives are being reexamined through new technology and renewed scrutiny of…

An astonishing discovery has left researchers QUESTIONING EVERYTHING WE KNOW ABOUT ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS, after SCIENTISTS REVEALED A LOST CITY HIDDEN DEEP UNDERWATER—IN A PLACE IT SHOULD NEVER HAVE BEEN. How could an advanced settlement exist where history says no civilization ever thrived, and WHAT CATACLYSM ERASED IT WITHOUT A TRACE? As sonar scans, impossible architecture, and unexplained artifacts come to light, one chilling question now confronts historians worldwide: DOES THIS SUNKEN CITY PROVE HUMAN HISTORY IS FAR OLDER—and FAR STRANGER—THAN WE’VE BEEN TOLD? 👉 CLICK THE ARTICLE LINK IN THE COMMENT to uncover the obscure evidence rewriting the story of our past.

Vast portions of the world’s ancient past remain unexplored, not because they are inaccessible in principle, but because they now…

Scientists Finally Unlocked The Secret Chamber Hidden Inside Egypt’s Great Pyramid

Inside the Great Pyramid and Beyond: Rethinking Ancient Technology, Lost Knowledge, and Forgotten Civilizations Deep within the Great Pyramid of…

Shocking: Jim Caviezel and Mel Gibson Reveal Behind-the-Scenes Secrets You’ve Never Heard Before

Behind one of the most controversial religious films ever produced lies a body of testimony that continues to unsettle those…

End of content

No more pages to load