An Ethiopian Manuscript and the Resurrection Reimagined

For centuries, the ancient city of Aksum has stood as a quiet witness to one of Christianity’s oldest continuous traditions.

Long before Europe’s great cathedrals rose, Ethiopian monasteries were already preserving sacred texts in stone-walled sanctuaries carved into cliffs and mountains.

While much of the early Christian world was shaped—and reshaped—by imperial councils, wars, and theological purges, the Ethiopian Highlands remained remarkably insulated.

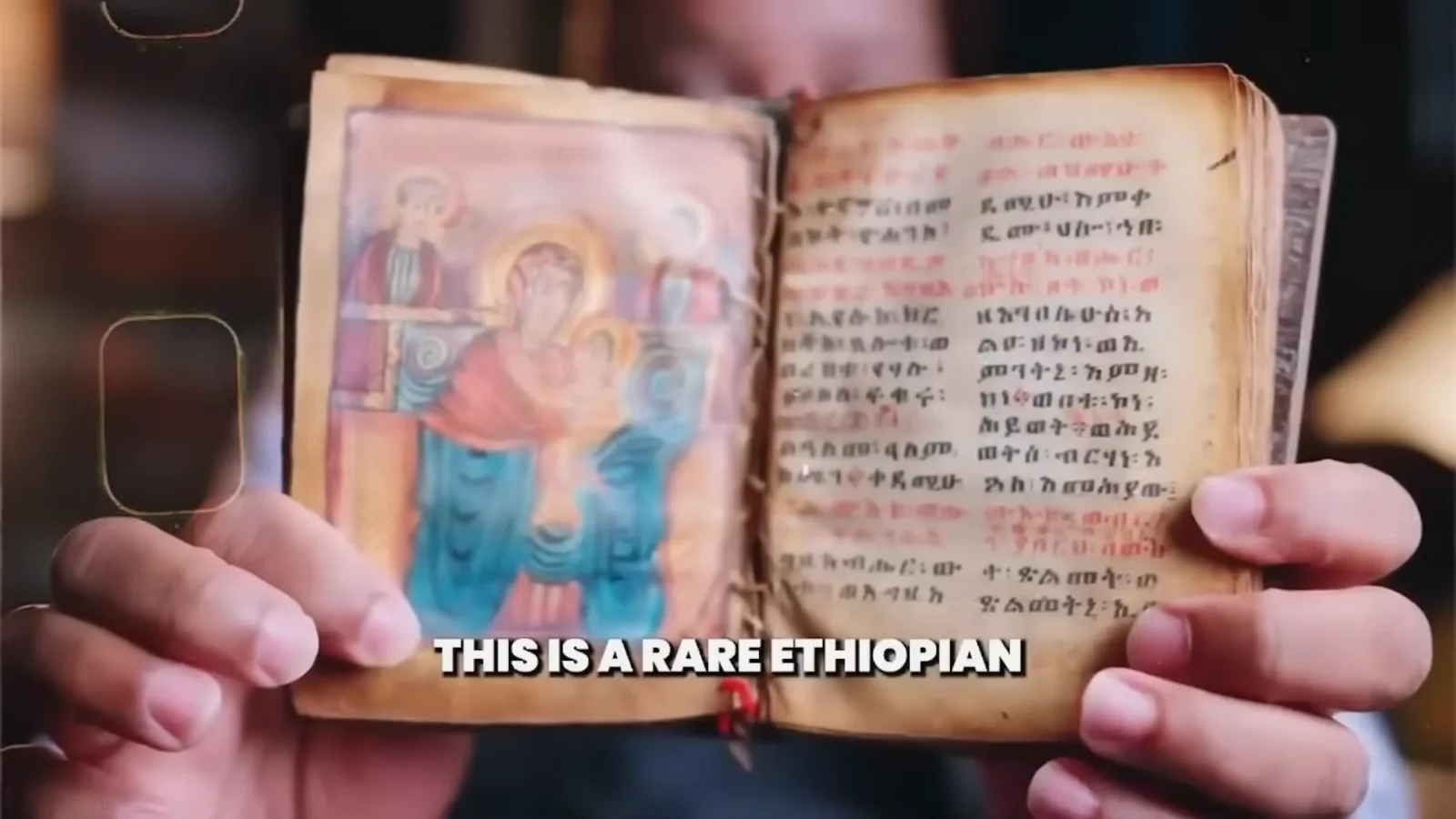

That isolation has now brought renewed global attention following the release of a translated passage from a fourth-century Ge’ez manuscript that presents an unfamiliar interpretation of the Resurrection.

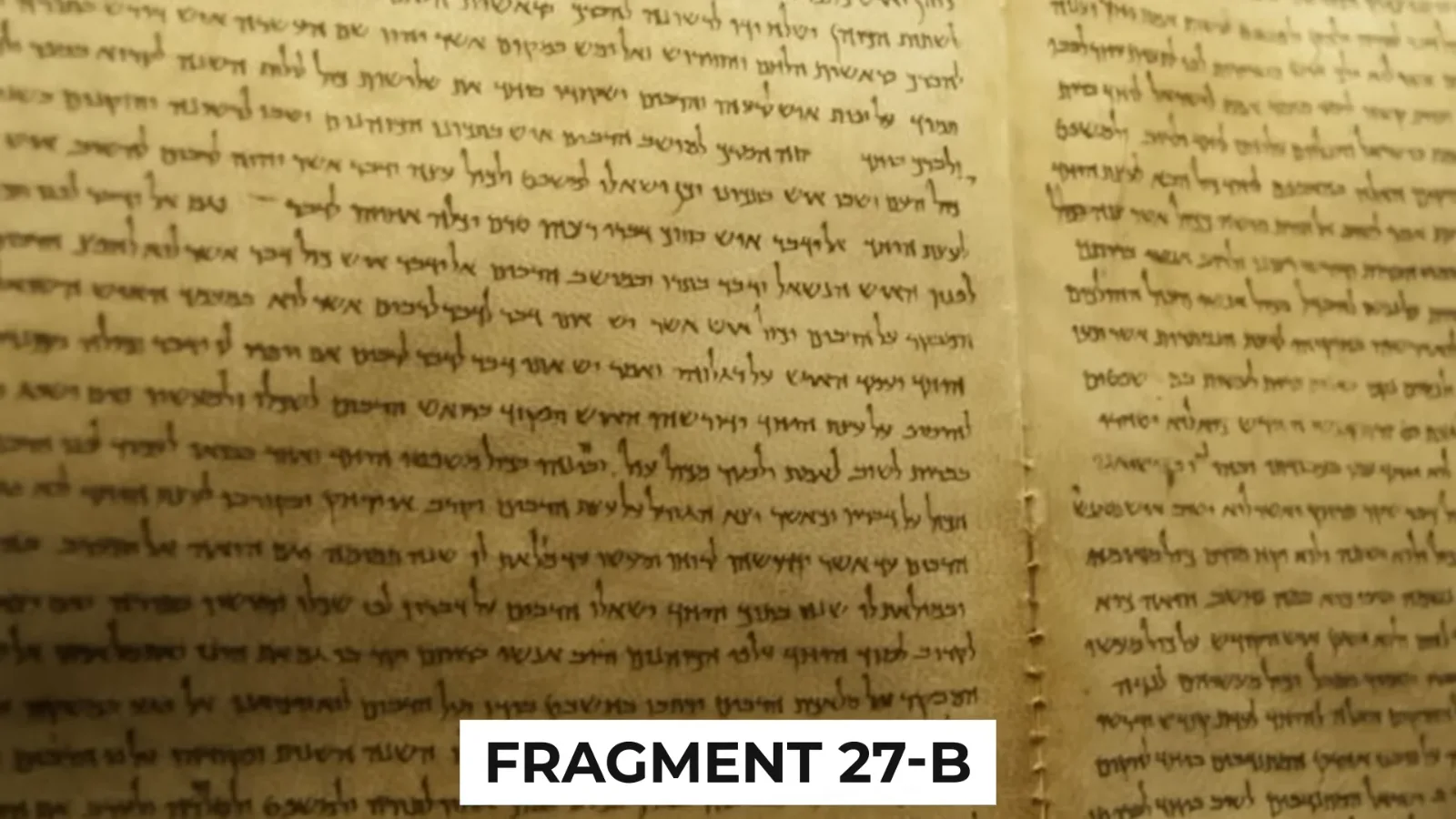

The text, known locally as Fragment 27-B and referred to by scholars as the “Resurrection Passage,” was preserved for more than sixteen centuries at the monastery of Debre Damo.

Its disclosure has prompted intense debate among theologians, historians, and linguists, not primarily because of its age, but because of its content.

Rather than reinforcing the familiar Western understanding of Easter as the physical resuscitation of a corpse, the passage describes the Resurrection as a transformation that transcends physical form altogether.

Debre Damo itself is emblematic of Ethiopia’s role in preserving early Christian literature.

Accessible only by climbing a sheer cliff with the aid of a rope, the monastery has long functioned as a natural archive, protected from conquest and outside scrutiny.

Manuscripts housed there were copied, stored, and revered as sacred inheritances rather than historical artifacts.

Fragment 27-B was among those texts treated with exceptional reverence, shielded from foreign scholars during the colonial era and excluded from modern scientific testing.

According to Ethiopian monastic tradition, sacred writings are not preserved for validation, but for continuity of faith.

The manuscript is written in Ge’ez, an ancient South Semitic language no longer spoken conversationally but still used in liturgy.

Ge’ez is known for its dense semantic structure, in which words carry layered meanings that blend theology, poetry, and philosophy.

Translating such texts into modern languages is not a simple act of substitution, but an interpretive process that requires cultural and theological fluency.

Ethiopian scholars emphasize that Ge’ez expressions often function as metaphors pointing beyond literal description.

When the translation was finally authorized by a council of senior monks, it immediately stood apart from the canonical Gospel narratives familiar to most Christians.

The passage does not open with the discovery of an empty tomb or with angelic messengers.

Instead, it focuses on a change in the surrounding reality itself.

The atmosphere, the perceptions of the witnesses, and the nature of Christ’s presence are described as fundamentally altered.

The body of Jesus is not said to rise in physical form but to enter a state described as luminous, living radiance.

Central to the passage is the Ge’ez term berhanawi, often translated as “luminous” or “radiant,” though scholars note that it also implies awareness and vitality.

In this account, Christ appears not as a recognizable physical body but as a manifestation of conscious light.

The women at the tomb encounter what the text describes as stillness rather than movement, presence rather than form.

Speech is portrayed as resonating internally rather than audibly, suggesting a mode of communication that bypasses the senses.

This portrayal diverges sharply from the bodily emphasis found in the Gospel of Luke or the Gospel of John, where touch, wounds, and shared meals underscore physical continuity.

In Fragment 27-B, the Resurrection is not framed as proof of divine power over biological death, but as evidence that death itself is not ultimate reality.

The text implies that what was transformed was not only Christ, but the structure of existence itself.

One of the most discussed sections involves a dialogue with Mary Magdalene.

In the canonical Gospel of John, she is told not to cling to Jesus.

In the Ethiopian passage, the meaning shifts.

Rather than discouraging physical contact, the text urges her to abandon attachment to former perceptions.

She is directed to recognize a similar radiance within herself, implying that the Resurrection is not an isolated event but a universal one.

This idea has led scholars to describe the passage as teaching a form of “universal resurrection,” in which the transformation initiated at the tomb extends to all humanity.

According to this interpretation, the event is not confined to a single body or moment in time, but represents a fundamental change in the relationship between life, death, and consciousness.

The three days traditionally associated with Christ’s burial are also reinterpreted.

Instead of a descent into an underworld, the Ge’ez verbs describe an act of repair or reweaving.

Death is depicted as a rupture in the fabric of creation, and the interval between crucifixion and reappearance as the time required to mend that rupture.

Christ is portrayed not merely as an individual restored to life, but as a unifying principle binding the material and spiritual realms.

The passage concludes with a statement that has proven especially controversial.

Rather than promising a future return “in the clouds,” it asserts that Christ has already returned within the breath of all living beings.

This line challenges traditional expectations of a Second Coming as a future historical event and places the kingdom of God within present experience rather than future anticipation.

The response from global religious institutions was swift.

The Vatican issued a cautious statement acknowledging Ethiopia’s ancient manuscript tradition while warning against deriving doctrine from isolated texts outside the consensus of early church councils.

Some theologians labeled the passage reminiscent of early movements deemed heretical by the institutional church, particularly those that downplayed the physical reality of Christ’s suffering and resurrection.

Academic reactions, however, were more divided.

Many scholars emphasized that Ethiopia’s Christian tradition developed largely outside the political influence of Rome and Constantinople.

As a result, texts preserved there were not subjected to the same processes of doctrinal standardization that shaped the New Testament canon in the Mediterranean world.

Historians note that Ethiopia’s Miaphysite theology—affirming a unified divine-human nature of Christ—provides a conceptual framework in which a luminous resurrection would not be considered problematic, but coherent.

Comparisons have already been drawn between Fragment 27-B and early Christian writings discovered at Nag Hammadi in Egypt, which also emphasize light, knowledge, and transformation.

Unlike those texts, however, the Ethiopian manuscript emerges from a continuous liturgical tradition rather than a buried archive.

This continuity has made it more difficult to dismiss as a later invention or marginal curiosity.

The survival of such a text is consistent with Ethiopia’s historical role as a guardian of early Christian literature.

The complete preservation of works such as the Book of Enoch and the Book of Jubilees—lost elsewhere for centuries—demonstrates how divergent streams of early Christianity endured beyond the reach of imperial orthodoxy.

In this context, Fragment 27-B is less an anomaly than a reminder of the diversity that characterized Christianity before doctrinal uniformity took hold.

The monks who authorized the translation have emphasized that they do not view the passage as a challenge to faith, but as a clarification of it.

From their perspective, the text was never hidden as a secret, only protected until a time when it could be approached without immediate rejection.

They argue that the modern world, shaped by both scientific inquiry and spiritual disillusionment, is better equipped to consider a resurrection understood as transformation rather than biological exception.

Whether Fragment 27-B will alter mainstream Christian theology remains uncertain.

What is clear is that it has reopened questions long considered settled.

By presenting the Resurrection as a cosmic event rather than a physical anomaly, the text invites reconsideration of foundational assumptions about life, death, and human potential.

The significance of the Ethiopian manuscript lies not in disproving established beliefs, but in expanding the historical record of how early Christians understood their central mystery.

It suggests that the Resurrection was once interpreted in ways that emphasized illumination over restoration, presence over return, and unity over separation.

In doing so, it reveals that the history of Christian thought is broader, more complex, and more contested than any single tradition has long acknowledged.

News

R Kelly sentenced to 30 years in prison for s*x abuse

R Kelly Sentenced to 30 Years in Prison: A Reflection on Justice and Accountability On June 30, 2022, R Kelly,…

R Kelly – Freedom (Official Music Video 2025) Out Now

R Kelly’s “Freedom”: A Powerful Anthem of Liberation R Kelly’s latest release, “Freedom,” officially launched on January 20, 2025, has…

R Kelly – Freedom (official music)

R Kelly’s “Freedom”: A Musical Journey Towards Liberation R Kelly’s latest release, titled “Freedom,” debuted on February 9, 2025, and…

R Kelly – I’m not asking for freedom I’m asking for forgiveness (official music video)

R Kelly’s “I’m Not Asking for Freedom, I’m Asking for Forgiveness”: A Soulful Plea for Redemption R Kelly’s latest release,…

R Kelly – I am Sorry America | A Cry For Freedom & Redemption

R Kelly’s “I Am Sorry America”: A Plea for Freedom and Redemption R Kelly’s latest release, titled “I Am Sorry…

I Was Trying to Live my Dream (R Kelly Songs of Freedom)

R Kelly’s “I Was Trying to Live My Dream”: A Reflection on Aspirations and Redemption The latest release from R…

End of content

No more pages to load