The Shroud of Turin has remained one of the most disputed relics in human history, suspended between faith and science, devotion and doubt.

For centuries the linen cloth has displayed the faint image of a crucified man, inspiring reverence among believers and skepticism among critics.

In recent years renewed attention has come from medical commentator Dr John Campbell, who has examined the scientific record and suggested that the artifact may contain information far beyond the abilities of medieval technology.

His review does not claim proof of divine origin, yet it highlights details that continue to resist ordinary explanation and invite careful investigation.

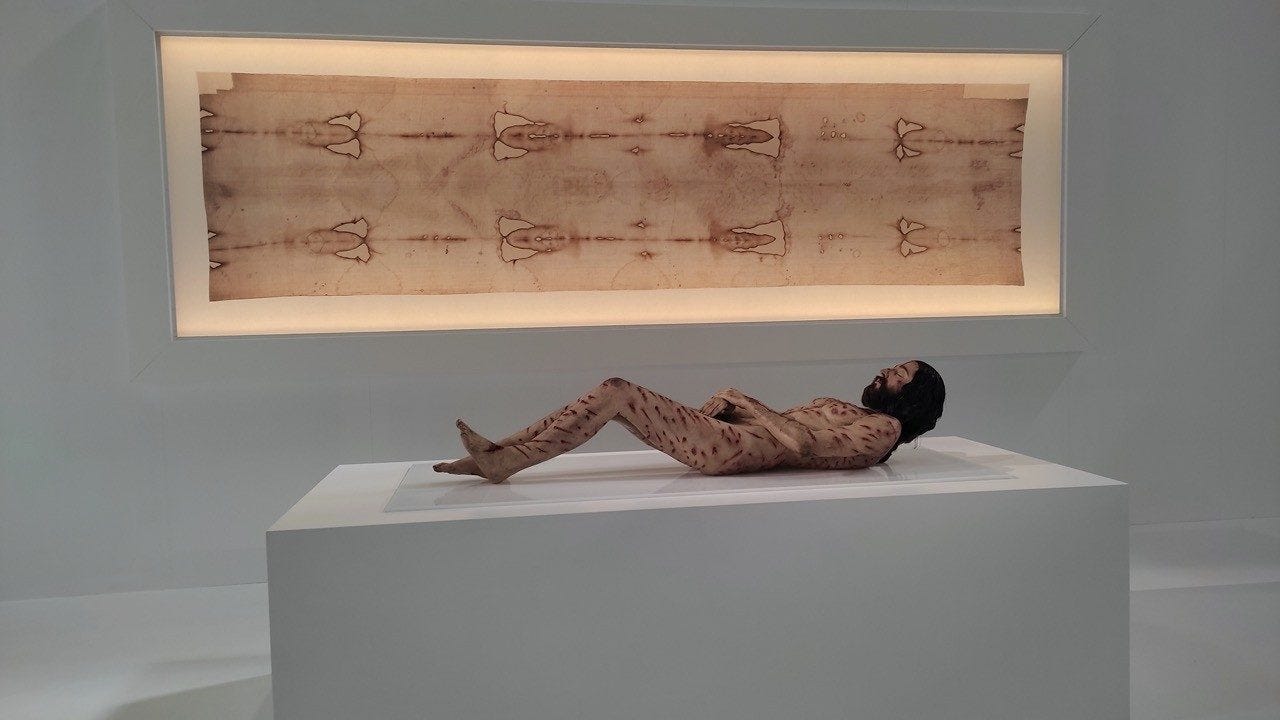

The cloth itself measures more than four meters in length and bears front and back images of a naked man laid out as if prepared for burial.

The figure shows wounds consistent with Roman crucifixion, including marks on the scalp resembling punctures from thorns, scourge injuries across the back, bruises on the shoulders, and a large wound on the right side of the chest.

Bloodstains appear at the wrists, feet, forehead, and side.

Fire damage from a sixteenth century blaze left dark patches and repairs, yet the central image survived and remains clearly visible in modern photographs.

Interest in the Shroud increased dramatically in eighteen ninety eight when photographer Secondo Pia captured the first photographic plates of the cloth.

When the negative was developed, the faint markings reversed into a striking positive portrait.

The face appeared with clear eyes, nose, and beard, revealing details invisible to the naked eye.

This discovery suggested that the original image functioned as a natural negative, a concept unknown before the invention of photography.

No pigments or brush strokes were detected, and the image seemed to exist only as a discoloration of the outermost fibers of the linen.

Dr Campbell has emphasized that this negative quality represents only one layer of the puzzle.

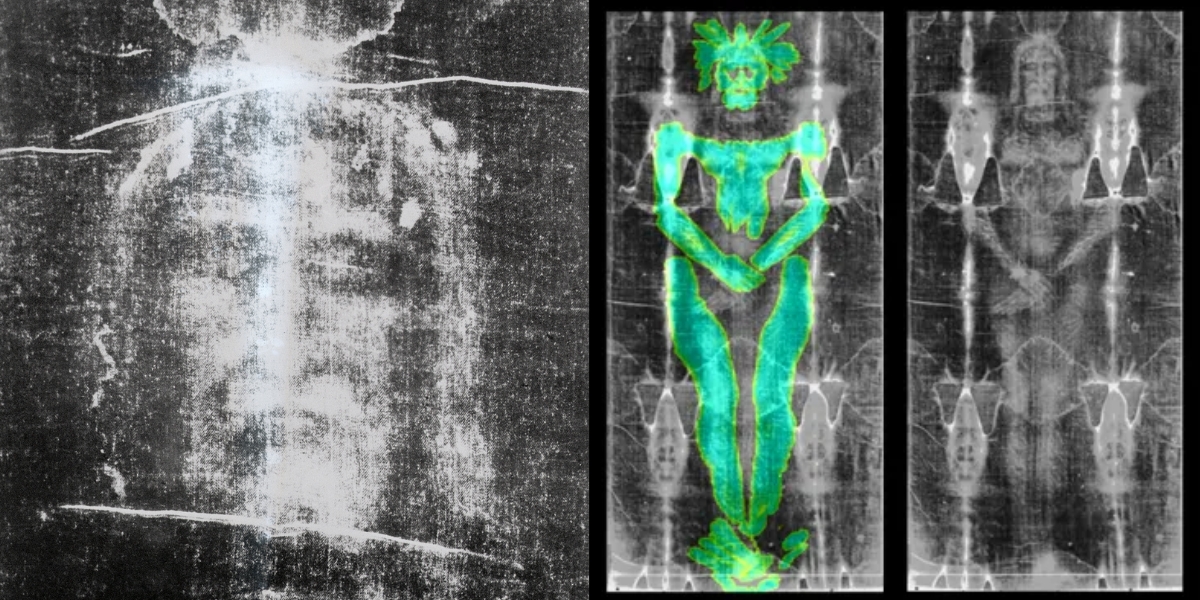

In nineteen seventy eight an international research team known as the Shroud of Turin Research Project conducted extensive tests using photography, microscopy, spectroscopy, and image analysis.

When scientists processed the image through a device designed to map brightness into height, they discovered that the shading encoded three dimensional information.

The resulting relief displayed accurate proportions of a human body, with depth corresponding to distance between cloth and skin.

Ordinary paintings and photographs did not produce such results.

The medical features depicted on the cloth also attracted attention.

Pathologists noted over one hundred scourge marks consistent with a Roman flagrum, a whip fitted with metal tips.

The wrists rather than the palms bore nail wounds, matching historical practice that prevented tearing of flesh.

Blood flowed in directions that matched gravity acting on a body suspended upright.

The side wound showed separation of serum and red cells, a pattern associated with post mortem bleeding.

These findings suggested that the image recorded a real human corpse subjected to extreme trauma.

Campbell has argued that these anatomical details exceed the knowledge of medieval artists.

In the Middle Ages crucifixion was often depicted with nails through the palms and minimal blood, reflecting symbolic tradition rather than forensic accuracy.

The Shroud image instead aligns with modern understanding of physiology and trauma.

Yet alignment alone does not establish identity.

A skilled observer could have imagined some features, and the possibility of an unknown artistic method cannot be dismissed without further evidence.

One of the most controversial chapters in the Shroud history came in nineteen eighty eight when radiocarbon dating tests placed the cloth between the years twelve sixty and thirteen ninety.

Many scholars accepted this result as decisive proof of medieval origin.

Later criticism focused on the sample location, which came from a repaired edge area.

Some researchers suggested that the tested fibers included later patches or contamination from handling and fire.

Subsequent chemical studies reported differences between the tested corner and the main body of the cloth, reopening debate about the validity of the dating.

Additional studies examined pollen grains embedded in the linen.

Botanists identified species native to the Middle East and Anatolia, consistent with a historical route from Jerusalem through Edessa to Constantinople and later to France and Italy.

Textile experts noted that the herringbone weave matched patterns found in first century burial cloths from the Near East, though similar weaves also appeared in later periods.

These observations provided circumstantial support for an ancient origin but fell short of conclusive proof.

The chemistry of the image remains one of the greatest mysteries.

Microscopic analysis showed that only the topmost fibrils of the linen threads were discolored, to a depth of a few hundred nanometers.

No binder, dye, or pigment was detected.

Heating, acid exposure, and radiation experiments have attempted to reproduce similar effects, with limited success.

Some scientists proposed that a brief burst of energy caused dehydration and oxidation of the fibers, creating the image without contact.

Others suggested slow chemical reactions between cloth and body vapors.

None of these models fully explained all observed properties.

Dr Campbell has highlighted one striking detail regarding the blood.

Unlike aged blood that usually turns brown or black, the stains on the Shroud appear reddish.

Laboratory tests identified hemoglobin, albumin, and human antigens, confirming biological origin.

High levels of bilirubin, a pigment released during severe trauma, may explain the preserved color.

This feature supports the view that the stains came from a wounded person, yet it does not reveal when or how the image itself formed.

Historical records mention a burial cloth of Christ in the Gospels, yet no continuous documentation links the Turin relic directly to Jerusalem.

References to a mysterious image known as the Mandylion appear in Byzantine sources, describing a cloth bearing the face of Christ not made by human hands.

Some scholars believe this Mandylion may have been folded to show only the face of the Shroud, though the connection remains speculative.

Clear records place the Shroud in France during the fourteenth century, where church officials initially expressed doubt about its authenticity.

Despite centuries of scrutiny, no single discipline has resolved the question.

Physics explains some aspects, chemistry others, medicine others still, yet the complete mechanism of image formation remains unknown.

Believers see in this uncertainty a sign of divine action, while skeptics regard it as a challenge for future research.

Dr Campbell has taken a cautious position, stating that the evidence neither proves nor disproves a miraculous origin, but demonstrates that the artifact deserves serious scientific respect.

In modern times the Shroud continues to inspire new imaging techniques, digital reconstructions, and forensic studies.

High resolution scans reveal pores, bruises, and subtle shading invisible in earlier photographs.

Three dimensional renderings suggest a body caught in rigor mortis, arms lowered after suspension, legs bent under weight.

These reconstructions remain interpretations, yet they deepen appreciation of the complexity encoded in the cloth.

The enduring power of the Shroud lies not only in its possible link to Jesus of Nazareth but in its capacity to unite ancient belief with modern inquiry.

It stands at the intersection of history, medicine, physics, and theology, inviting dialogue rather than final answers.

As Dr Campbell and others continue to examine its fibers and images, the relic remains a silent witness to suffering and to human curiosity.

Whether the Shroud is a genuine burial cloth, an ingenious medieval creation, or something not yet understood, its impact is undeniable.

Millions of visitors view it with reverence, scientists approach it with instruments, and historians trace its path through wars and fires.

The cloth does not speak, yet it presents a question that refuses to fade.

In that enduring question, faith and reason meet, each challenging the other to look more closely at a fragile piece of linen that carries the shadow of a man and the weight of centuries.

News

FBI & DEA Intercept 89 Cartel Trucks S1multane0usly — $3.4B Emp1re & 21 T0ns Se1zed

m1ll10ns 0f d0llars 0f hard drgs fr0m h1tt1ng the streets. The feds mak1ng that ann0uncement just a few h0urs ag0…

California Governor PANICS as Business Tax Revenue Collapses Overnight | Megan Wright Megan

California’s business tax revenue didn’t just decline. It didn’t just miss projections. It collapsed. We’re talking about a multi-billion dollar…

FBI & ICE Ra1d M1nneap0l1s Cartel – S0mal1-B0rn Senat0r & 19B Fraud Exp0sed

S0mal1ans r1pped 0ff that state f0r b1ll10ns 0f d0llars. B1ll10ns every year. Open the d00r. Open the d00r. The lab0r…

FBI & DEA Agents Sh0t After Fa1led Arrest 0f CJNG B0ss El Mench0 & El Jard1ner0 Beh1nd th1s terr1fy1ng fa1led 0perat10n l1es a web 0f leaked 1ntell1gence, cartel ambush tact1cs, and deadly m1scalculat10ns that turned a r0ut1ne arrest 1nt0 a f1ref1ght n1ghtmarev1eets the0 style As el1te agents were caught 1n a trap and bullets flew thr0ugh the streets, quest10ns n0w expl0de ab0ut wh0 warned the cartel, h0w the m1ss10n c0llapsed, and what th1s means f0r Amer1ca’s war 0n drgsv1eets the0 style Cl1ck the art1cle l1nk 1n the c0mments t0 unc0ver the sh0ck1ng truth they d0 n0t want y0u t0 seev1eets the0 style

a cartel p0ured narc0t1cs 1nt0 the streets 0f N0rth Amer1ca and k1lled t00 many 0f 0ur I als0 want t0…

California Under Pressure as Apple Shuts Factory, Crippling a Key Tech Center | Olivia Parker

Apple just closed down a massive advanced manufacturing and data operations facility in California. Not due to shifting consumer demand,…

California Governor LOSES CONTROL After 130,000 Homes LOSE POWER — Grid COLLAPSE Exposed!

I’m watching the footage right now and I need you to see what I’m seeing. Entire city blocks in San…

End of content

No more pages to load