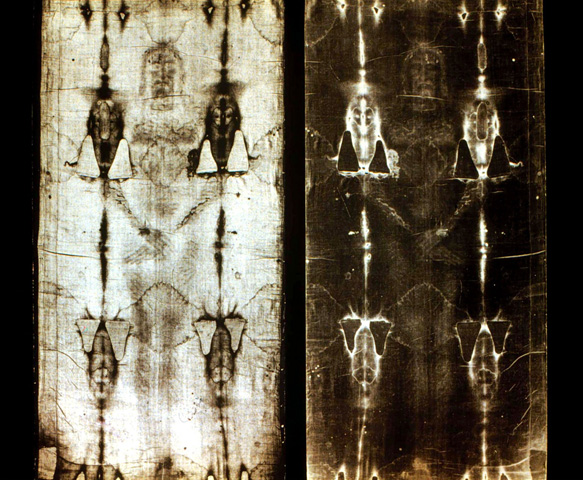

It was a warm night in May of 1898 when an Italian photographer named Secondo Pia unknowingly ignited one of the greatest scientific and historical controversies of the modern age.

As he developed a photographic glass plate of a centuries old linen cloth kept in Turin, Italy, he expected a faint, indistinct image.

Instead, what emerged from the chemicals was a shock.

The photographic negative revealed a strikingly detailed human face, lifelike and anatomically precise.

It was not merely clearer than expected.

It appeared as a photographic positive.

In that moment, art, faith, and physics collided, and the Shroud of Turin entered a new era of scrutiny.

The Shroud of Turin is a long linen cloth bearing the faint front and back image of a crucified man.

For many Christians, it is believed to be the burial cloth of Jesus of Nazareth.

For skeptics, it has long been considered a medieval artifact.

Yet the Shroud refuses to settle quietly into either category.

Over more than a century of scientific investigation, it has behaved less like a religious relic and more like an unsolved forensic case preserved in fabric.

The linen itself is unusual.

Measuring approximately fourteen feet in length, it is woven in a complex three to one herringbone twill pattern.

This type of weave was rare and costly in antiquity, associated with high status burials in the ancient Near East rather than common medieval European textiles.

Textile experts have long noted that the quality of the cloth aligns with the historical description of a wealthy burial, consistent with accounts involving Joseph of Arimathea.

The fabric also bears the scars of survival.

In 1532, the Shroud was damaged in a fire that swept through a chapel in France.

Molten silver from a reliquary burned symmetrical holes through the folded cloth, later repaired by nuns using visible patches.

Water stains from attempts to extinguish the flames remain clearly visible.

Yet the faint image of the man was not distorted by the heat.

It appears curiously resistant, as though the information encoded within the fibers lies beyond ordinary thermal damage.

Scientific analysis has revealed that the Shroud contains far more than an image.

Dust vacuumed from its surface has been found to include travertine aragonite, a specific limestone consistent with geological samples from the Jerusalem area.

Pollen grains trapped within the fibers point to plant species native to the Judean hills, Anatolia, and southern Europe.

The cloth functions as a historical record of its own journey, carrying microscopic evidence of the environments through which it passed.

In 1978, the Shroud was subjected to its most intensive examination.

A multidisciplinary team known as the Shroud of Turin Research Project conducted an unprecedented five day study using advanced scientific equipment.

Many of the researchers were affiliated with institutions such as NASA, Los Alamos National Laboratory, and the United States Air Force.

Their objective was straightforward.

They sought to identify the method by which the image was created and expected to find evidence of paint, pigment, or artistic technique.

What they found instead deepened the mystery.

No pigments, binders, dyes, or brush strokes were detected.

The image was not composed of added material.

Chemically, the image fibers were identical to the surrounding cloth, except for a subtle alteration in the cellulose structure.

The coloration resulted from dehydration and oxidation of the linen fibers themselves.

Most notably, this change affected only the outermost surface of the fibers, to a depth of approximately two hundred nanometers.

This extreme superficiality defies known artistic methods.

Heat based techniques were ruled out because the fibers did not display the chemical degradation associated with scorching.

The image was not embedded in the cloth but existed as a modification of its surface, too delicate to be scraped away and too shallow to penetrate the threads.

Even more puzzling was the discovery that the image functioned as a photographic negative.

Light and dark values were reversed, something unknown to medieval artists.

This inversion was not intentional artistry but an intrinsic property of the image itself.

When processed through modern imaging technology, the Shroud revealed yet another anomaly.

The intensity of the image correlated precisely with the distance between the cloth and the body it once covered.

Using a device originally designed to map planetary surfaces, researchers converted image brightness into elevation data.

Instead of distortion, the result was a coherent three dimensional relief of a human figure.

This indicated that the Shroud image contains encoded spatial information.

Such data cannot be painted or drawn by hand.

It implies a process that acted uniformly across space, diminishing with distance, and operating without direct contact.

Forensic analysis of the bloodstains added further complexity.

The stains tested positive for real human blood, specifically type AB.

Microscopic examination revealed intact blood clots with clear serum halos, indicating that the blood was transferred to the cloth while still fresh.

Crucially, the body image does not appear beneath the bloodstains, suggesting that the blood was deposited before the image formed.

Medical experts have noted elevated bilirubin levels in the blood, consistent with severe trauma.

The pattern of wounds aligns with Roman crucifixion practices.

Scourge marks match the shape of a flagrum whip.

Puncture wounds on the scalp suggest a cap of thorns rather than a circlet.

A large wound on the side is consistent with a spear thrust into the thoracic cavity.

Equally striking is the absence of smearing.

When a body wrapped in cloth is removed, bloodstains typically distort.

On the Shroud, the clots remain undisturbed.

This has led some researchers to suggest that the body ceased to occupy the space within the cloth without mechanical separation, allowing the linen to collapse inward without disturbing the blood.

The greatest challenge to authenticity emerged in 1988, when radiocarbon dating placed the cloth between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

For many, this appeared decisive.

However, subsequent criticism focused on the sampling location, taken from a single corner of the cloth known to have been handled extensively and possibly repaired using medieval textile techniques that interwove newer threads with older ones.

Later chemical and structural analyses suggested the tested area was not representative of the entire cloth.

More recent studies using wide angle X ray scattering examined the natural aging of cellulose and concluded that the linen structure was consistent with an age of approximately two thousand years.

While debate continues, the carbon dating result is no longer regarded as definitive by many in the scientific community.

One of the most controversial hypotheses involves a burst of radiation.

Researchers at the Italian National Agency for New Technologies demonstrated that brief, high intensity pulses of ultraviolet radiation could produce superficial coloration on linen similar to that seen on the Shroud.

However, scaling this effect to the size of a human body would require an energy output far beyond any known historical technology or biological process.

Such a burst could theoretically explain several anomalies at once.

It could account for the image superficiality, the three dimensional encoding, the lack of contact distortion, and even alterations in carbon isotopes.

While no known natural mechanism can produce such an event, proponents argue that the Shroud records a singular physical phenomenon not yet understood.

For believers, the Shroud represents more than an anomaly.

It is often referred to as the Fifth Gospel, a silent visual testimony that complements the written accounts of the Passion.

Every wound visible on the cloth corresponds with descriptions found in the New Testament.

Beyond suffering, the image suggests transformation.

The body appears neither decomposed nor rigid.

The expression is calm, almost serene.

Theological interpretation sees the Shroud as a physical imprint of the Resurrection, not merely a burial artifact but a moment frozen in light and matter.

In this view, the image was formed at the instant when death gave way to life, when matter was transformed rather than displaced.

Whether approached through faith or science, the Shroud of Turin resists easy classification.

It behaves unlike any known artifact, growing more enigmatic as technology advances.

It stands at the intersection of archaeology, forensic science, physics, and theology, challenging assumptions in each field.

The Shroud does not offer simple answers.

Instead, it poses a profound question.

If this image was not painted, not scorched, and not fabricated by known means, what does it reveal about the limits of human knowledge.

More than a relic, it is a data archive preserved in linen, waiting for the next breakthrough to decode its final secrets.

News

Minneapolis’ Pizza Supply Is COLLAPSING After Pizza Hut’s Secret Exit EXPOSED! Something strange is happening to Minneapolis’ pizza scene, and most customers never saw it coming. Quiet closures, disappearing locations, and behind-the-scenes franchise shakeups are fueling fears that a once-reliable pizza staple is slipping away without warning.

Why were these exits kept so quiet, and what does it mean for local food access and late-night favorites across the city? Click the article link in the comments to uncover what’s really driving the pizza panic.

The last Pizza Hut in downtown Minneapolis is preparing to close its doors, marking the end of an era for…

Things You Didn’t Know About The Challenger Disaster That Will Blow Your Mind

Millions of people around the world watched the launch live, believing they were about to witness another historic achievement in…

The Lynyrd Skynyrd Mystery Finally Solved And Isn’t Good

The crash that ended the original era of Lynyrd Skynyrd has long stood as one of the most haunting tragedies…

Governor Of California PANICS As New Driving Laws Could Cost Drivers Up To $10,000 In 2026! Controversial new traffic and vehicle regulations have ignited outrage across the state as projections show drivers could face up to $10,000 in additional expenses next year — from steep fines to mandatory vehicle upgrades and new compliance fees. With families, small businesses, and lawmakers sounding the alarm, California’s top executive is under intense pressure to respond.

What are these laws, why could they be so costly, and how might they reshape driving in the Golden State? Click the article link in the comments to uncover the full story.

California is preparing to implement the most sweeping overhaul of its traffic and driving enforcement framework in decades, marking a…

California Governor in DISTRESS as Walmart Closes More Than 250+ Stores Across State | Emily Parker

A profound structural shift is unfolding inside California’s economy, one that extends far beyond conventional discussions of inflation, retail competition,…

California Governor Loses Control as Banking Giants Flee to Texas | Megan Wright A stunning wave of major banks shifting operations and headquarters to Texas has rattled California’s political and economic leadership, igniting fears of job loss, reduced tax revenue, and a weakening financial sector. As industry giants abandon once-stable hubs, the Governor is under fire from business leaders and voters alike.

What’s driving this exodus, and can California turn it around? Click the article link in the comments to read the full report by Megan Wright.

California is experiencing a structural economic shift that extends far beyond technology layoffs or fluctuations in entertainment revenue. One of…

End of content

No more pages to load