The Shroud of Turin: Science, History, and an Enduring Mystery

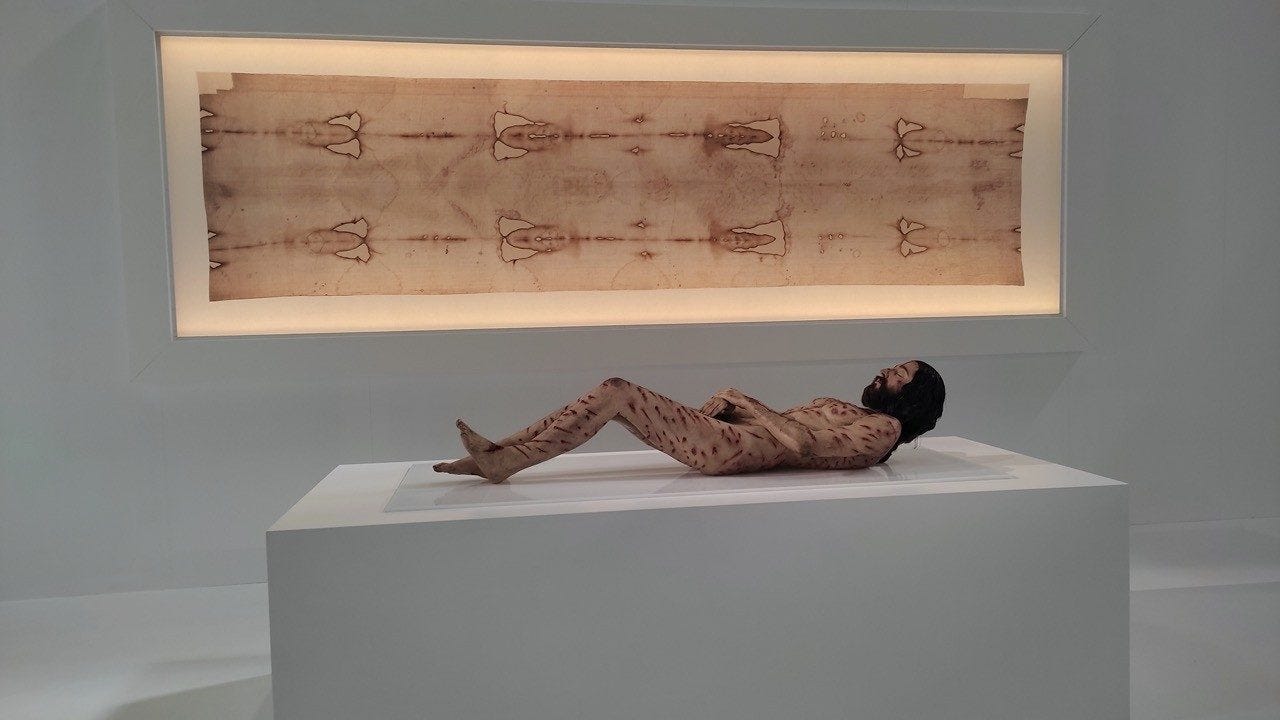

For centuries, a length of ancient linen housed in the Cathedral of St.John the Baptist in Turin, Italy, has stirred devotion, skepticism, and scientific fascination in equal measure.

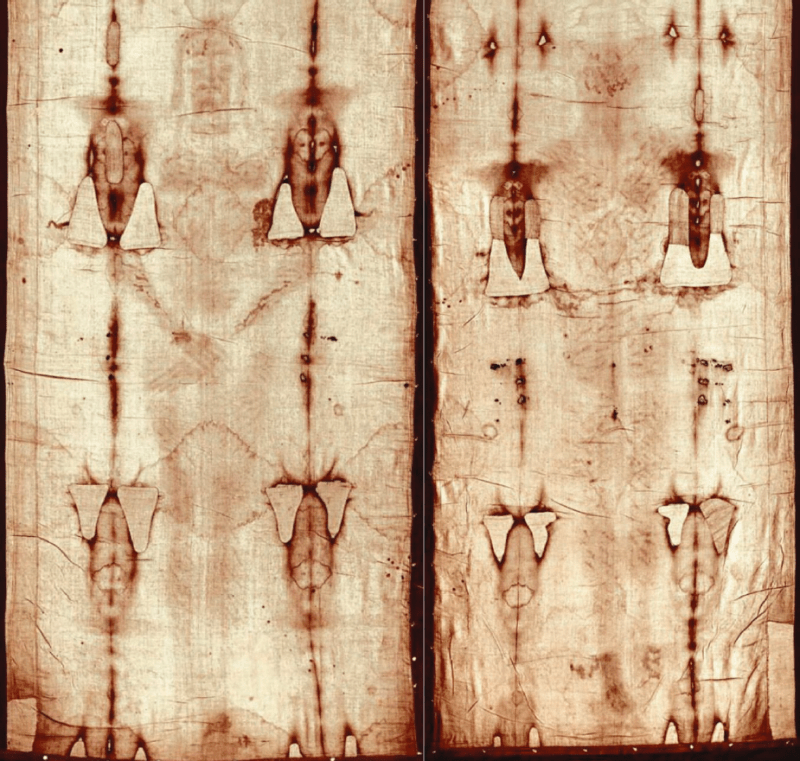

Known as the Shroud of Turin, the cloth bears the faint front-and-back image of a man who appears to have been scourged, crowned with thorns, and crucified according to Roman practice.

To believers, it may be the burial cloth of Jesus Christ.

To skeptics, it is a medieval artifact elevated by faith and tradition.

In recent years, renewed attention from commentators such as Dr.John Campbell has once again placed the shroud at the center of public debate, highlighting discoveries that continue to challenge conventional explanations.

The shroud measures roughly fourteen feet in length and three and a half feet in width.

Across its surface appears a ghostlike image of a bearded man with long hair, visible in both frontal and dorsal views.

The body shows numerous wounds: marks consistent with flogging, punctures around the scalp resembling a crown of thorns, bruises on the shoulders, abrasions on the knees, nail wounds in the wrists and feet, and a large wound in the right side of the chest.

These details align closely with descriptions of Roman crucifixion recorded in the Christian Gospels.

Historical references to the shroud begin in the mid-fourteenth century in France, where it was displayed as a sacred relic.

From there, it traveled through various European courts before arriving in Turin in 1578.

Over the centuries it endured damage, most notably during a fire in 1532 that scorched and burned parts of the cloth.

Yet the central image survived, leaving intact a haunting portrait that has continued to intrigue scholars and worshippers alike.

One of the most striking developments in the shroud’s modern history occurred in 1898, when Italian photographer Secondo Pia took the first photographs of the cloth.

When Pia developed his photographic plates, he made a startling discovery: the negative revealed a far clearer and more detailed face than could be seen by the naked eye.

Light and dark appeared reversed, suggesting that the image on the shroud itself behaves like a photographic negative.

At a time when photography was still a relatively new technology, the finding raised profound questions about how such an effect could have been produced centuries earlier.

In 1978, an international team of scientists and engineers known as the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP) conducted the most comprehensive scientific examination of the cloth to date.

Over five days, the team used a wide array of instruments, including X-ray fluorescence, ultraviolet and infrared spectroscopy, and high-resolution photography.

Their conclusions ruled out the presence of paint, dye, or pigment responsible for the image.

Microchemical tests found no evidence that the image had been applied with a brush or created using known artistic techniques.

Perhaps even more remarkable was the discovery that the image contains three-dimensional information.

Using a NASA-developed VP-8 image analyzer, researchers found that variations in image intensity corresponded to the distance between the cloth and the body it covered.

When processed, these variations produced a coherent three-dimensional representation of a human form.

Ordinary photographs do not yield such results.

The presence of encoded depth data suggested that the image formation process was unlike any conventional method of imaging known in art or photography.

The image itself is extraordinarily superficial.

Microscopic analysis shows that only the topmost fibers of the linen—measuring just a few micrometers thick—are discolored.

The coloration does not penetrate the threads or reach the reverse side of the cloth.

Instead, it appears confined to a thin layer of dehydrated cellulose on the fiber surfaces.

Attempts to replicate this effect using heat, chemicals, or lasers have produced partial imitations but have failed to reproduce the full range of features present on the shroud.

Bloodstains on the cloth add another layer of complexity.

Chemical tests have detected hemoglobin, human albumin, and other components consistent with human blood.

Some researchers have reported that the blood may be of type AB, although this finding remains debated.

Under magnification, the stains exhibit serum halos, a pale ring that forms when blood separates into red cells and plasma.

Such features are characteristic of real blood, not paint.

Remarkably, the blood retains a reddish color rather than turning dark brown, which some scientists attribute to high levels of bilirubin—a pigment associated with severe trauma.

Forensic specialists who have studied the image note its anatomical accuracy.

The placement of the nail wounds in the wrists rather than the palms reflects Roman crucifixion techniques, which required nails to pass through stronger wrist bones to support the body’s weight.

The pattern of scourge marks corresponds to a Roman flagrum, a whip with multiple leather thongs tipped with metal.

The side wound appears consistent with a spear thrust delivered after death, matching descriptions in the Gospel of John.

The posture of the figure also offers clues.

The arms are crossed over the pelvis, the legs slightly bent, and the body appears rigid, as though captured in the early stages of rigor mortis.

Subtle distortions in the image suggest that the body had been suspended vertically before being laid horizontally, consistent with crucifixion followed by burial.

These details, while open to interpretation, have impressed many medical experts with their coherence and realism.

Despite these findings, the shroud’s authenticity has been strongly challenged by radiocarbon dating.

In 1988, samples taken from a corner of the cloth were tested independently by laboratories in Oxford, Zurich, and Tucson.

All three produced similar results, dating the linen to between 1260 and 1390.

The conclusion seemed decisive: the shroud was a medieval creation.

Over time, however, doubts arose about the validity of the sampling.

The tested material came from an area near the edge of the cloth, close to patches added after the 1532 fire.

Later textile analyses suggested that the sample may have included a mixture of original fibers and medieval repair threads.

If true, the contamination would have skewed the results toward a younger age.

Critics argued that a single small sample could not represent the entire cloth.

More recent studies using alternative methods have reopened the question of dating.

Spectroscopic analyses and X-ray techniques have suggested an age consistent with the first century.

Comparisons of the weave pattern with textiles recovered from Masada, a first-century Jewish fortress, have found similarities in style and construction.

Pollen grains identified on the cloth correspond to plants native to the Middle East, including species found around Jerusalem.

Traces of limestone dust resembling that of Jerusalem tombs have also been reported, though these findings remain contested.

Dr.John Campbell, a former nurse educator and popular science commentator, has drawn renewed public attention to these unresolved issues.

In discussing the shroud, he emphasizes its unusual properties: the negative image, the three-dimensional data, the superficial fiber discoloration, and the apparent absence of any known mechanism capable of producing such an effect in antiquity.

He has also noted the historical irony that many Protestants, following the rejection of relics by figures such as John Calvin, long ignored the shroud, potentially overlooking a unique artifact worthy of scientific study regardless of religious belief.

Theories attempting to explain the image range widely.

Some propose that it resulted from a chemical reaction between the cloth and gases released by a decomposing body.

Others suggest a form of medieval artistry now lost to history.

A more speculative hypothesis invokes a brief burst of radiant energy that altered the linen fibers in proportion to their distance from the body, encoding both the image and its three-dimensional information.

While intriguing, such ideas remain unproven and lie beyond the scope of established physics.

What continues to distinguish the shroud from ordinary artifacts is the convergence of disciplines it attracts.

Physicists analyze its image formation, chemists examine its fibers and stains, medical experts study its wounds, historians trace its journey across Europe, and theologians reflect on its possible spiritual significance.

Few objects have been subjected to such sustained and diverse scrutiny.

Yet consensus remains elusive.

Skeptics point to the radiocarbon dates, the late medieval appearance of the shroud in historical records, and the powerful influence of faith in shaping interpretations.

Believers counter with the anatomical precision, the unexplained imaging properties, and the accumulating evidence that challenges a medieval origin.

Between these positions lies a vast field of unresolved questions.

The shroud’s enduring appeal may lie precisely in this tension.

It occupies a boundary where science meets belief, where laboratory instruments probe what many regard as sacred.

For some, it offers a tangible link to the central figure of Christianity, a silent witness to suffering and death.

For others, it stands as a remarkable example of how human history, technology, and devotion can combine to produce an object of lasting mystery.

As analytical techniques continue to advance, new studies may yet clarify aspects of the shroud’s origin and formation.

Non-destructive testing, improved imaging, and more representative sampling could yield insights unavailable to earlier generations.

Even so, it is unlikely that every question will be answered.

The shroud has survived fires, wars, and centuries of debate, retaining its power to provoke wonder and controversy.

In the end, the Shroud of Turin remains what it has long been: a linen cloth bearing an image that resists easy explanation.

Whether regarded as a medieval icon, an extraordinary natural imprint, or the burial cloth of Jesus of Nazareth, it continues to challenge assumptions about art, science, and history.

Its faint figure, etched on fragile fibers, stands as a reminder that some mysteries endure not because they lack investigation, but because they invite it endlessly.

News

California Governor Alarmed as Supply Chain Breakdown Worsens — Megan Wright Quiet disruptions are now turning into visible shortages as internal reports warn of ports backing up, warehouses stalling, and critical routes failing across the state. Emergency meetings inside the governor’s office suggest officials fear a cascading collapse no one planned for.

What triggered this breakdown, which industries are already suffering, and how close is California to a full logistics crisis? Click the Article Link in the Comments to See What the Data Is Now Revealing.

Something is beginning to fracture across California, not because of a single storm, a single strike, or a single political…

Spencer and Monique Tepe — 6 Steps Investigators Can Take To Solve The Case

In the quiet hours before dawn, an Ohio family was erased in an act of violence that stunned an entire…

“I Was Married To Debra Newton” — 2nd Husband Tells All

For more than four decades, Michelle Marie Newton did not know she was missing. She grew up believing she was…

“YOUR NAME IS MICHELLE NEWTON” — Truth Revealed After 42 Years

For more than four decades, Michelle Marie Newton did not know she was missing. She grew up believing she was…

Why Are Florida Residents Fleeing Their Homes? Homes Falling Into The Ground

The official Vatican logbook for that evening recorded nothing unusual. It listed the date, the hour, the papal signature, and…

Pope Leo XIV Ordered a Meeting With Cardinal Tagle… What Happened After Was Erased From the Records

The official Vatican logbook for that evening recorded nothing unusual. It listed the date, the hour, the papal signature, and…

End of content

No more pages to load