For centuries, Cleopatra VII has been remembered as the most beautiful woman in history—a seductive queen whose charm bent the fate of empires.

Art, literature, and film have reinforced this image, portraying her as a near-mythical figure of physical perfection and irresistible allure.

Yet modern science and archaeology are quietly dismantling this legend.

Emerging evidence suggests that Cleopatra’s greatest struggle may not have been against Rome, but against the fragile biology of her own bloodline.

The renewed fascination with Cleopatra’s DNA does not begin with a laboratory, but with an archaeological mystery buried beneath the Egyptian desert.

For nearly two thousand years, the location of Cleopatra’s tomb has remained one of history’s greatest unanswered questions.

Most scholars long assumed it was lost beneath modern Alexandria, swallowed by earthquakes and the Mediterranean Sea.

But one researcher refused to accept that conclusion.

Kathleen Martínez, a former criminal lawyer turned archaeologist from the Dominican Republic, approached Cleopatra’s disappearance not as legend but as a cold case.

Rejecting conventional assumptions, she developed a psychological and political profile of the queen and followed it westward to the ancient temple complex of Taposiris Magna.

There, after years of excavation, Martínez and her team made a startling discovery: a vast underground tunnel carved through solid limestone, extending more than 4,300 feet toward the sea.

Archaeologists described the structure as an engineering marvel, comparable to the ancient Greek Tunnel of Eupalinos.

The scale and precision of the tunnel suggested that Taposiris Magna was far more than a minor religious site.

Nearby evidence of a submerged port reinforced the idea that this complex once held great ceremonial and political importance.

Martínez proposed a bold theory: Cleopatra deliberately chose this remote location to hide her tomb from Roman desecration.

Defeated by Octavian, she would never have allowed herself to be paraded through Rome in chains.

Instead, she sought eternal union with Mark Antony and burial as the earthly embodiment of the goddess Isis, sealed away where no conqueror could violate her legacy.

Within the temple grounds, further discoveries deepened the mystery.

Sixteen rock-cut tombs revealed mummies unlike any others found in Egypt.

Each had been buried with a gold amulet shaped like a tongue placed inside the mouth.

In ancient Egyptian belief, such “golden tongues” granted the deceased the ability to speak before Osiris in the afterlife.

The presence of so many of these amulets in one location suggested ritual significance.

Martínez proposed that these individuals were not random elites, but members of Cleopatra’s inner court—courtiers buried in preparation for the arrival of their queen.

While Cleopatra’s tomb has yet to be found, scientists believed they already possessed a genetic key to her identity through the remains of her sister and rival, Arsinoe IV.

Arsinoe was Cleopatra’s most dangerous internal enemy, a rival who once seized the throne and even managed to trap Julius Caesar during his Egyptian campaign.

After her eventual defeat, Arsinoe was exiled to Ephesus, where she was later assassinated on Cleopatra’s orders—a crime that shocked the ancient world.

In the early twentieth century, archaeologists uncovered an unusual octagonal tomb in Ephesus known as the Octagon.

Inside lay a skeleton believed to belong to a young royal woman.

Many scholars identified it as Arsinoe, citing the tomb’s architecture and historical location.

If correct, this skeleton could offer insight into Cleopatra’s ancestry, health, and physical appearance.

Early interpretations of the remains sparked intense debate.

Based on early skull measurements and photographs, some researchers claimed the bones suggested African ancestry, fueling arguments that Cleopatra herself may have been mixed-race.

This hypothesis gained traction in both academic and popular culture, challenging the long-held view that the Ptolemaic dynasty was ethnically Greek.

However, modern science would ultimately overturn this narrative.

In 2022, researchers rediscovered the long-lost skull in the archives of the University of Vienna.

Using advanced micro-CT scanning and DNA extraction from the dense petrous bone, scientists conducted a far more accurate analysis.

The results, published in 2025, were definitive and shocking.

The skeleton was not Arsinoe.

It was not even female.

The DNA revealed the presence of a Y chromosome.

The individual was an adolescent boy between the ages of 11 and 14, suffering from severe developmental disorders.

His skull showed asymmetry, stunted jaw growth, and signs consistent with genetic disease.

Genetic markers traced his ancestry not to Egypt or North Africa, but to southern Europe, possibly Italy or Sardinia.

The Octagon tomb, once thought to hold a murdered princess, was instead a heroon—a monument honoring a mysterious, semi-divine figure whose true identity remains unknown.

This discovery dismantled the idea that Arsinoe’s remains provided direct insight into Cleopatra’s biology.

With that mirror shattered, historians were forced to return to what is known with certainty: Cleopatra’s lineage.

And that reality proved darker than any debate over ethnicity.

Cleopatra was born into the Ptolemaic dynasty, a Greek royal family that ruled Egypt for nearly three centuries.

Determined to preserve power and legitimacy, the Ptolemies practiced systematic incest, marrying siblings and close relatives generation after generation.

Cleopatra’s own parents were almost certainly full siblings.

Her grandparents were likely uncle and niece, or worse.

Geneticists describe this phenomenon as “pedigree collapse,” where a family tree folds inward instead of expanding.

Cleopatra’s estimated coefficient of inbreeding may have exceeded 45 percent—nearly double that of famously inbred European monarchs such as the Habsburgs.

In most cases, such extreme inbreeding leads to devastating physical and cognitive disorders.

The Ptolemaic family history is filled with obesity, deformity, weakness, and instability.

Yet Cleopatra herself defies this expectation.

Historical sources describe her as intelligent, charismatic, multilingual, and politically formidable.

She ruled for over two decades, bore four children, and commanded armies and navies.

This contradiction has led scholars to two competing interpretations.

One theory argues that Cleopatra was a genetic miracle—an extraordinarily rare individual who inherited just enough healthy genes to escape the worst physical consequences of her ancestry.

The other suggests she did not escape at all, but instead learned to survive within a compromised body.

Ancient descriptions hint at this possibility.

Coins minted during her reign depict a strong aquiline nose, a prominent chin, and a thick neck—traits common within her family.

Plutarch famously noted that her beauty was not exceptional, emphasizing instead her voice, intellect, and presence.

He also described her as physically small enough to be carried concealed in a sack, suggesting a petite stature possibly linked to growth restriction.

Medical historians now speculate that Cleopatra may have suffered from inherited metabolic or endocrine disorders, including conditions resembling Graves’ disease, which can cause hyperactivity, insomnia, intense energy, and emotional volatility.

These traits align eerily well with historical accounts of her relentless stamina and high-risk decision-making.

If Cleopatra lived with chronic pain, hormonal imbalance, or skeletal weakness, she may have compensated through intellect, strategy, and chemistry.

Egypt was the pharmaceutical center of the ancient world, and Cleopatra was known to study medicine and cosmetics.

She authored treatises on pharmacology and beauty, experimenting with compounds derived from plants, minerals, and resins.

Substances such as opium, kyphi incense, and blue lotus were widely available and used for pain relief, sedation, and mood regulation.

Cosmetics may have served not merely aesthetic purposes, but as tools to mask physical symptoms—reshaping eyes, concealing swelling, and reinforcing the image of a living goddess.

Seen through this lens, Cleopatra emerges not as a flawless seductress, but as a brilliant survivor—someone who mastered image, chemistry, and diplomacy to overcome the genetic consequences of a collapsing dynasty.

Her alliances with Julius Caesar and Mark Antony may have served not only political ambition, but biological necessity, ensuring her children were free from the incest that destroyed her lineage.

Today, as excavations continue beneath Taposiris Magna, the stakes of discovering Cleopatra’s tomb have transformed.

Archaeologists are no longer searching merely for a queen, but for biological truth.

Her remains, if found, would offer unprecedented insight into ancient genetics, royal inbreeding, and human resilience.

Whether Cleopatra proves to have been a genetic miracle or a silent sufferer, one conclusion is clear: the reality of the last Pharaoh is far more complex, and far more human, than the legend that survived her.

And perhaps that complexity—carefully concealed in life and preserved in mystery—was her greatest triumph of all.

News

Muslims Stormed a Church to Burn the Eucharist Then THIS HAPPENED…

I led seven men into a Catholic church to burn what Christians called the body of Christ, convinced we were…

Muslims Stormed a Church to Steal the Communion Unaware What Jesus Had Planned…

Four Muslim men walked into a church to prove Christianity was fake by taking communion and feeling nothing. What happened…

Arab Royal Mocked Jesus Publicly in Dubai, Then Dropped to One Knee in Shock vd

On December 15th, 2018, I stood before 5,000 Muslims in Dubai and spent 45 minutes mocking Jesus Christ, calling him…

A Catholic Mass Was Interrupted When Muslim Men Stole Chalice—What Happened Next Shocked Everyone

On December 8th, 2019, I walked into a Catholic church with three other Muslim men and grabbed the sacred cup…

R Kelly Thrown In “The Hole” After Alleged Prison Assassination 😳 New Trial Filing GOES LEFT

Our Kelly’s legal team just dropped bombshell allegations claiming the singer is not just serving time. He’s literally fighting for…

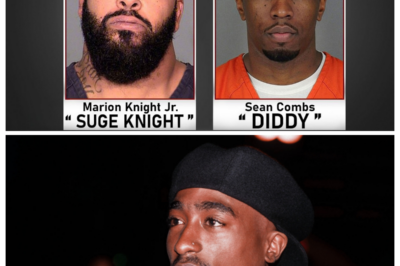

Diddy & Suge Knight CHARGED For Tupac’s Death

Nearly three decades after the death of Tupac Shakur, renewed debates continue to surface regarding who was ultimately responsible and…

End of content

No more pages to load