For more than seven centuries a single piece of linen has stood at the center of one of the most enduring religious mysteries in human history.

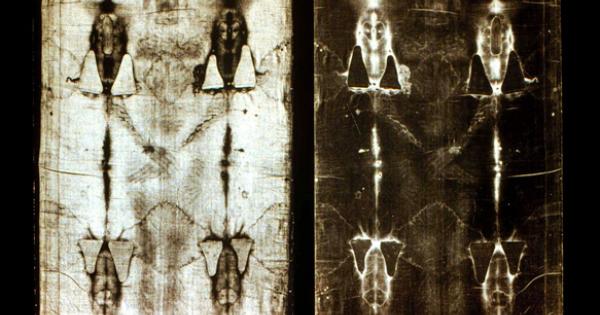

Known as the Shroud of Turin, the cloth bears the faint outline of a human figure and stains that resemble blood.

Many believers regard it as the burial cloth that once wrapped the body of Jesus Christ after the crucifixion.

Skeptics have long dismissed it as a medieval forgery.

Recent scientific studies have renewed global attention, raising new questions about origin, age, and authenticity while reminding scholars that the debate remains far from settled.

The Shroud is a long rectangle of twill fabric that displays front and back impressions of a bearded man who appears to have suffered wounds consistent with Roman crucifixion.

For centuries it has been preserved in northern Italy, drawing pilgrims, historians, and scientists alike.

The cloth entered public record in the middle of the fourteenth century when it appeared in a small church in Lirey in France.

How it arrived there remains unknown.

Church authorities acknowledged its presence, but no documentation traced its path from the ancient world to medieval Europe.

Legends soon emerged.

According to tradition the cloth had traveled from Judea to Turkey, then to Constantinople, where it was guarded by Byzantine custodians for generations before vanishing and reappearing in France.

None of these claims could be confirmed.

Yet the Shroud gained an aura of sanctity that endured for centuries.

Thousands of pilgrims traveled to see what they believed was the cloth that once covered the most famous man in history.

In the late twentieth century the Catholic Church permitted scientific testing.

In 1988 samples were taken and examined by laboratories in Oxford, Zurich, and Arizona using radiocarbon dating.

The results suggested that the fabric was produced between the years 1260 and 1390.

This placed its creation firmly in the medieval period, long after the time of Jesus.

For many scholars the verdict seemed decisive.

The Shroud appeared to be an elaborate religious artifact rather than a relic from the first century.

The reaction was immediate and intense.

Believers argued that the samples might have been taken from patched or contaminated sections of cloth.

Critics questioned whether repairs and handling over centuries could have altered the carbon content.

Others proposed extraordinary explanations.

Some geologists suggested that a powerful earthquake described in the Gospel of Matthew might have released neutrons that interfered with the dating process.

According to this theory radiation could have shifted the measured age of the linen.

Most physicists dismissed the idea as speculative, but the debate refused to fade.

A new chapter opened in 2015 when a team led by Italian geneticist Gianfranco Borrini analyzed microscopic dust particles collected from the surface of the Shroud.

These particles contained traces of both plant and human DNA.

The researchers focused on mitochondrial DNA, which is passed through maternal lines and can reveal geographic ancestry.

Their findings suggested that the cloth had been touched by people from many regions, including North Africa, East Africa, the Middle East, and parts of Asia.

Plant DNA revealed an equally complex picture.

Traces of Mediterranean garlic, European conifers, North American trees, and East Asian plum were detected.

Some genetic markers pointed toward regions near the Middle East and the Caucasus, areas close to where the burial of Jesus would have occurred according to scripture.

One lineage appeared linked to a community with roots in the eastern Mediterranean.

Most surprising was the presence of ancient genetic fragments associated with India, suggesting that the linen might have originated there before traveling west.

The interpretation of these results sparked immediate controversy.

Critics noted that the Shroud had been displayed publicly for centuries and handled by countless visitors, clergy, and scientists.

Modern contamination could easily explain the diversity of genetic material.

Editors and researchers from societies devoted to Shroud studies emphasized that identifying plant and human traces on an exposed artifact did not prove its age or origin.

They argued that the data revealed little about whether the cloth dated from the time of Jesus or from the medieval era.

Some skeptics suggested that the Indian genetic material might have been introduced during twentieth century examinations by researchers from South Asia.

Others pointed out that pollen studies conducted decades earlier had produced inconclusive and sometimes contradictory results.

Without direct testing of the flax fibers themselves, many scholars concluded that DNA analysis alone could not resolve the question of authenticity.

While debate continued over the Shroud, archaeologists in Jerusalem were uncovering new evidence linked to another central element of Christian tradition, the tomb of Jesus.

In October 2016 a multinational team restored the small shrine that encloses a burial chamber within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

The project marked the first time in centuries that the stone covering the burial shelf was removed.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre stands in the heart of Jerusalems old city, near sites revered by Jews, Christians, and Muslims alike.

According to Christian tradition the complex marks both the place of crucifixion and the location of the empty tomb where Jesus was laid and later resurrected.

Over nearly two thousand years the church has endured destruction, fire, earthquake, and reconstruction.

Despite its importance scholars have long debated whether it truly stands above the historical burial site.

The restoration project was led by engineers and archaeologists from the National Technical University of Athens.

When they removed layers of marble and debris, they uncovered a limestone surface believed to be the original burial bench.

Representatives of Roman Catholic, Greek Orthodox, and Armenian churches were present as witnesses.

Those who observed the chamber described a powerful moment, noting that the tomb had remained sealed since at least the middle ages.

Historical records suggest that Roman Emperor Constantine I ordered the first church built on this site in the fourth century.

After adopting Christianity, Constantine sent envoys to locate the tomb described in scripture.

Local guides directed them to a Roman temple erected during the reign of Emperor Hadrian.

According to ancient historians Hadrian had built the pagan shrine deliberately to suppress Christian worship.

Constantine demolished the structure and excavated beneath it.

When a burial cave was identified he ordered the construction of an elaborate basilica around it, leaving the tomb exposed as a focal point of pilgrimage.

The original church did not survive intact.

Arab forces captured Jerusalem in the seventh century.

Though early rulers tolerated Christian worship, unrest later led to partial destruction.

In the early eleventh century the Fatimid caliph al Hakim ordered the church demolished almost entirely.

Crusaders rebuilt it in the twelfth century, shaping much of the structure visible today.

Fires and earthquakes in later centuries caused further damage and restoration.

Despite this turbulent history the identification of the tomb site remained consistent.

Archaeologists noted that the limestone bench uncovered during the 2016 project matched burial practices from the first century.

The surrounding rock showed signs of quarrying consistent with the period.

While absolute proof remained impossible, many scholars concluded that the location was at least a plausible candidate for the burial of Jesus.

The findings highlighted a broader challenge facing biblical archaeology.

The earliest surviving copies of the Gospels were written decades after the events they describe.

Roman crucifixion is well documented in texts, yet physical evidence is rare.

Only two skeletons bearing signs of crucifixion have been discovered, neither linked to Jesus.

Archaeology can illuminate context and custom, but it cannot confirm resurrection or divine identity.

Tradition holds that a wealthy follower named Joseph of Arimathea arranged the burial.

Scripture describes how he wrapped the body in linen and placed it in a rock cut tomb sealed with a stone.

Three days later followers claimed the tomb was empty.

Whether the Shroud of Turin could be that linen remains the central question.

Modern science continues to advance.

Techniques now allow geologists to trace the origins of stone with remarkable precision.

Similar methods may one day determine the geographic source of ancient flax fibers.

For now the Shroud remains suspended between faith and skepticism, its image neither fully explained nor fully dismissed.

The continuing fascination reflects more than curiosity about an artifact.

It reveals a deep human desire to touch the past and find physical connection to sacred stories.

For believers the Shroud offers a tangible link to the suffering and resurrection of Christ.

For scientists it represents a complex puzzle shaped by contamination, history, and limited data.

For historians it is a reminder of how relics can shape devotion, politics, and culture across centuries.

As research proceeds scholars urge caution.

Extraordinary claims demand rigorous evidence.

Each new study adds detail but also new uncertainty.

The cloth has traveled through war, worship, fire, and flood.

It has absorbed dust from pilgrims, smoke from candles, and fibers from restorations.

Untangling this history may prove as difficult as interpreting the faint image itself.

Whether the Shroud is a medieval masterpiece or an ancient relic, its power endures.

It continues to draw millions to Turin and to inspire debate across theology, archaeology, and genetics.

Like the tomb in Jerusalem, it stands at the crossroads of belief and evidence.

The mystery has not been solved.

Instead it has deepened, reminding the modern world that some questions resist easy answers and that history often speaks in whispers rather than certainties.

News

5 MINUTES AGO: Princess Anne CONFIRMS the Saudi Dossier Is Real — Harry in Tears Over Meghan

Royal Dossier Crisis Reshapes the British Monarchy Five minutes before dawn the palace confirmed what royal insiders had whispered for…

Governor Of California LOSES IT After Gas Stations Are Closing Fast in Major Cities!

California entered the first days of 2026 facing an unexpected shock to its fuel distribution network as hundreds of gasoline…

California Just BANNED 70,000 Truckers — Then THIS Happened…

Seventy thousand independent truck drivers in California faced a sudden and unsettling discovery when a new worker classification law placed…

1 MIN AGO: FBI & ICE STORM Minneapolis — Shooting UNLEASHES Cartel War & Somali Mayor FALLS

On a frozen Minneapolis street, a single gunshot shattered years of secrecy. Shortly after dawn, during a routine immigration enforcement…

11 Incorrupted Bodies Of Saints Of The Catholic Church

The Mystery of Incorrupt Saints: When Faith Confronts the Limits of Science Crowds have recently gathered in a small Midwestern…

FBI Raids Hidden Chinese Fentanyl Precursor Lab in CA — $500M Seizure Crushes Cartel Supply Chain

Inside Project Red Phoenix: How Federal Agents Dismantled a Global Fentanyl Precursor Network At 11:47 a.m. Pacific time, federal prosecutors…

End of content

No more pages to load