Florida’s Everglades are facing one of the most severe ecological crises in their modern history, driven by the unchecked spread of Burmese pythons, an invasive predator that has fundamentally altered the region’s wildlife balance.

After decades of failed control efforts, researchers and wildlife officials have turned to an unconventional solution that blends biology with advanced engineering.

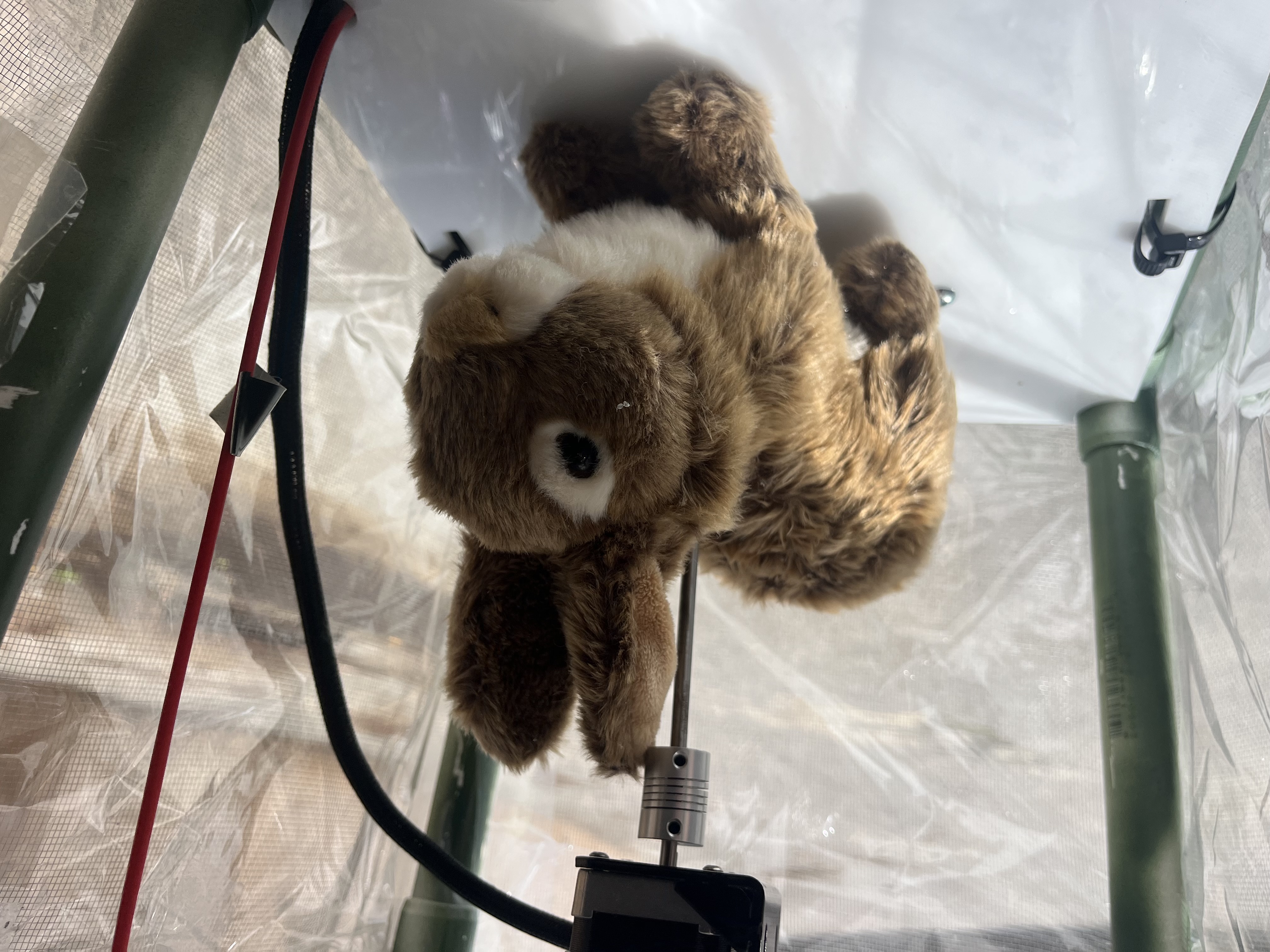

Hundreds of robotic rabbits are now being deployed across the wetlands, not as curiosities or experiments in novelty, but as carefully designed tools meant to expose and capture one of the most elusive predators on the continent.

The presence of Burmese pythons in Florida began quietly and without immediate alarm.

In the late twentieth century, the snakes were imported into the United States as exotic pets.

When young, they were manageable and visually striking, making them popular among reptile enthusiasts.

As the snakes grew larger, stronger, and more difficult to care for, many owners released them into the wild.

Others escaped during powerful storms and hurricanes that damaged private enclosures and pet facilities.

Florida’s warm, humid climate closely resembled the python’s native habitat in Southeast Asia, allowing the species to thrive almost immediately.

Within a few years, subtle warning signs began to appear across the Everglades.

Residents reported missing pets.

Wildlife officers noticed unusual tracks in the mud and a sudden drop in sightings of familiar animals.

Marsh rabbits, raccoons, foxes, and ground nesting birds began to vanish.

What initially seemed like isolated incidents soon revealed a broader pattern.

Scientific surveys confirmed that populations of some small mammals had declined by more than ninety percent in certain areas.

The once vibrant wetlands grew unnervingly quiet.

Burmese pythons proved devastatingly effective as predators.

Some individuals exceeded twenty feet in length and weighed more than two hundred pounds.

They hunted silently, blending almost perfectly into tall grass and murky water.

With no natural predators in Florida capable of controlling their numbers, the snakes spread rapidly.

A single female python can lay up to one hundred eggs in a single breeding season, accelerating population growth at a pace native species could not withstand.

Even alligators, long considered apex predators of the Everglades, were found dead after encounters with large pythons.

As the ecological damage became undeniable, Florida launched a series of aggressive response efforts.

Traditional traps proved ineffective, as the snakes rarely encountered them and often avoided unfamiliar objects.

Chemical controls were ruled out due to the risk they posed to non target species and water quality.

Wildlife agencies organized public hunting initiatives, including the highly publicized Python Challenge, which offered cash rewards to participants who captured or killed snakes.

Thousands of people joined the effort, but the results were deeply disappointing.

The vastness of the Everglades and the python’s natural camouflage made detection extraordinarily difficult.

Professional bounty hunters were later employed, paid both hourly and per captured snake.

While experienced and well equipped, they too struggled to make a measurable impact.

The snakes remained largely invisible, moving silently through millions of acres of dense swamp.

Costs escalated, frustration mounted, and the ecosystem continued to deteriorate.

It became clear that conventional methods alone would not solve the problem.

In an effort to rethink the challenge, scientists turned to detection dogs.

Specially trained canines were introduced to the Everglades to identify the unique scent of live Burmese pythons.

These dogs demonstrated remarkable accuracy, locating snakes hidden deep in vegetation or water that human searchers would never have found.

Early results were encouraging and offered a rare sense of optimism.

However, the harsh conditions of the wetlands posed serious risks.

Extreme heat, sharp sawgrass, deep water, and the ever present danger of a python strike limited how widely the program could expand.

Training and maintaining enough dogs to cover the entire ecosystem would require enormous resources.

The partial success of the canine program led researchers to an important realization.

Innovation worked, but it had to be scalable, resilient, and capable of operating continuously without risk to living partners.

That realization gave rise to one of the most unusual wildlife management strategies ever attempted in Florida.

Biologists studying python behavior identified one prey species that consistently attracted the snakes: the marsh rabbit.

These small mammals had suffered some of the steepest population declines since the python invasion.

Initial experiments using live rabbits as bait confirmed that pythons were drawn quickly and reliably to their presence.

However, the ethical and logistical problems were obvious.

The rabbits were often killed, the approach was expensive, and it could not be expanded safely.

Engineers and wildlife scientists then proposed a radical alternative.

Instead of using live animals, they would build artificial prey.

The result was the development of robotic rabbits designed to replicate the sensory signals that pythons rely on when hunting.

These devices were built to move in lifelike patterns, emit realistic body heat, and release carefully formulated scents that mimicked real mammals.

Each unit was powered by solar energy and reinforced to withstand heat, water, and mud for extended periods.

Hidden sensors and cameras were embedded within the decoys, allowing them to transmit real time data to nearby monitoring teams.

This marked a significant shift in invasive species control.

The technology was no longer limited to tracking or observation.

It actively engaged the predator by exploiting its instincts.

When the first group of robotic rabbits was deployed quietly into the Everglades, researchers expected cautious results.

What they observed instead was startling.

Within hours, motion sensors detected movement.

Burmese pythons began approaching the decoys from multiple directions.

Some attacked immediately, striking and coiling around the artificial prey.

Others circled slowly, displaying behavior that suggested hesitation or confusion.

A small number withdrew altogether.

For scientists, this behavior was unprecedented.

It was the first documented evidence that wild pythons might hesitate when confronted with unfamiliar prey that still triggered their sensory cues.

The robotic rabbits provided more than an opportunity to capture snakes.

They generated invaluable data about approach patterns, strike timing, and decision making.

Researchers began to analyze whether the snakes were capable of learning from repeated encounters.

Early successes followed quickly.

Several large pythons were captured near the decoys, including breeding females carrying eggs.

Removing these individuals prevented the addition of hundreds of offspring into the ecosystem.

At the same time, the collected data allowed scientists to identify high risk areas and seasonal movement patterns with greater accuracy than ever before.

Despite the promise, the program faces significant challenges.

Each robotic rabbit costs thousands of dollars to produce and maintain.

Deploying enough units to cover large portions of the Everglades requires continued funding, engineering improvements, and logistical planning.

Researchers are now testing more affordable materials, improved solar efficiency, and advanced scent delivery systems to extend operational life.

The robotic rabbits are also only one part of a broader technological vision.

Engineers are experimenting with upgraded versions equipped with heat sensors, enhanced cameras, and artificial intelligence systems capable of distinguishing python behavior from other wildlife.

Drones may soon complement the decoys by scanning wetlands from above, creating a layered monitoring network that operates both day and night.

Still, experts caution against viewing the technology as a final solution.

Nature adapts.

Early signs suggest that some pythons may already be modifying their behavior, altering movement patterns or strike timing in response to unfamiliar stimuli.

This evolutionary pressure means that control strategies must continue to evolve just as quickly.

Florida’s struggle with the Burmese python has lasted for decades, and no single intervention has delivered a decisive victory.

Yet for the first time, researchers believe the balance may be shifting.

The robotic rabbit program demonstrates that innovation, when guided by deep ecological understanding, can challenge even the most formidable invasive species.

The Everglades remain a battleground, but they are no longer defenseless.

The outcome of this experiment may influence how invasive species are managed worldwide, showing that technology can play a central role in restoring damaged ecosystems.

Whether machines can ultimately outpace evolution remains uncertain.

What is clear is that the fight has entered a new phase, one defined by creativity, persistence, and a willingness to rethink humanity’s relationship with nature.

News

Why Are Federal Officials Reportedly STUNNED by What Newly Released Data in Texas Just Revealed?

Texas stands at the center of national attention as the fastest growing state in the United States. Over the past…

Did Pope Leo XIV Announce a “New Commandment” Said to Come Directly From God—and Why Is the Church Reacting So Strongly?

Silence settled over Saint Peters Square as Pope Leo XIV appeared on the central balcony in the pale light of…

Did FBI & DHS Really Storm a U.S. Airport VIP

The United States government moved toward a new phase of counter narcotics enforcement as federal authorities outlined an unprecedented mission…

Why Was Pope Leo XIV Allegedly Barred from Entering the Cathedral

Early summer sunlight bathed the cobblestone streets of Rome in a warm glow as Pope Leo XIV traveled toward the…

Outrage erupted online after reports spread that Pope Leo XIV

The Catholic world has been thrust into profound uncertainty after Pope Leo XIV delivered a message that is now reverberating…

A dramatic story circulating online claims that during a pivotal moment inside the Vatican

The day began as one of ritual and order, a morning designed for ceremony rather than conflict. From the first…

End of content

No more pages to load