15,000 ft beneath the Atlantic Ocean, a deep sea camera pushed through the twisted corridors of a graveyard.

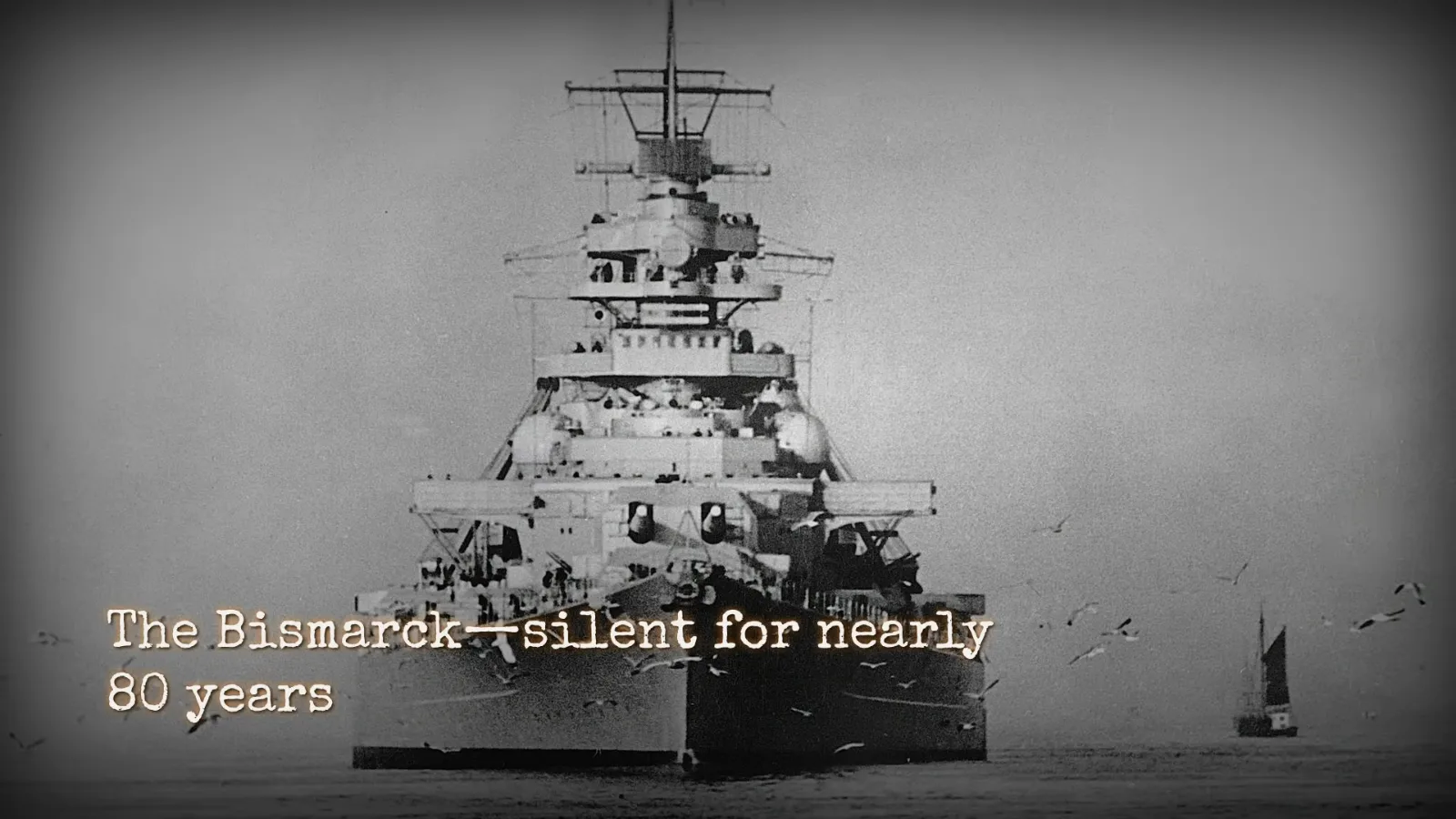

Bismar, Hitler’s most powerful warship, had rested here in silence for nearly 80 years.

But when explorers finally breached the Admiral suite in 2019, their cameras captured something that contradicted every official account of the ship’s final moments.

Documents perfectly preserved in the crushing darkness told a story that both Germany and Britain had spent [music] decades trying to bury.

What they found proves one of World War II’s greatest cover-ups.

The pride of the Creeks marine.

The Bismar wasn’t just a battleship.

She was a statement.

when she slid down the slipways at Blowman and Voss in Hamburgg on February 14th, 1939, 50,000 people gathered to witness the launch of what would become the most feared warship in the Atlantic.

At 41,000 tons fully loaded, stretching over 800 feet from bow to stern, she represented everything the Third Reich wanted the world to believe about German engineering and military might.

Her construction had taken nearly 3 years.

Eight 15-in guns sat [music] in four massive turrets capable of hurling shells weighing nearly a ton over 20 m [music] with devastating accuracy.

Her armor belt measured nearly 13 in thick in places.

Designed to withstand punishment from any gun afloat.

12 high-pressure boilers fed three turbine sets, giving her a top speed of 30 knots.

But more than her specifications, [music] the Bismar carried something else, something intangible.

She carried Germany’s pride and perhaps more dangerously, Hitler’s obsession.

Admiral Gunther Luchins commanded her.

A career naval officer, Luchins was 52 years old when he raised his flag aboard the Bismar in May 1941.

Tall, austere, with a reputation for tactical brilliance and personal courage.

He understood what his ship represented.

He also understood the mission ahead would either [music] cement the marines dominance over the Atlantic or end in catastrophe.

There would be no middle ground.

The British knew the Bismar was coming.

Intelligence reports had tracked her working up in the Baltic.

Reconnaissance flights photographed her in Norwegian fjords, but knowing [music] she existed and stopping her were two entirely different problems.

The Royal Navy had ruled the waves for centuries, but now they faced a vessel that challenged that supremacy at its core.

What nobody knew then, what would not be discovered until cameras reached the ocean floor decades later, was that both sides would have reasons to lie about what happened next.

Operation Rhino Bong, exercise rin began on May 18th, 1941.

The plan was elegant in its simplicity and devastating in its potential.

The Bismar, accompanied by the heavy cruiser Prince Jugan, would break out into the North Atlantic and wreak havoc on the convoy routes that kept Britain alive.

Every week, dozens of merchant ships crossed from America carrying food, fuel, weapons, [music] and raw materials.

Sever that lifeline and Britain would starve.

Churchill knew it.

Hitler knew it and Luchianis knew it.

The two ships left Gotenhoffen, modern-day Gdinia in Poland undercover of darkness.

They sailed north along the Norwegian coast, refueling in Bergen before making their dash through the gap between Iceland and Greenland.

British intelligence spotted them, but the Denmark Strait was wide, the weather was terrible, and the Germans were fast.

If they could slip through, they would disappear into the vast Atlantic hunting grounds.

May 23rd, 1941, the heavy cruisers, HMS Norfolk and HMS Suffuk, picked up the German ships on radar in the Denmark Strait.

The weather was exactly what Luchins had hoped for.

Snow squalls and mist, visibility dropping to less than a mile.

But the British had something the Germans did not fully appreciate yet.

Effective surface search radar.

Suffix Type 279 radar painted the Bismar at 13 mi and the cruisers began to shadow, staying just out of range, reporting the German position every few minutes.

Admiral John Tovi, commanding the British home fleet from HH S.

King George 5, began moving his pieces across the board.

The battle cruiser HMS MS Hood, Pride of the Royal Navy, and the new battleship HMS Prince of Wales raced to intercept.

They had one chance.

If the Bismar made it past them into the open Atlantic, finding her again would be nearly impossible.

The stage was set for one of naval warfare’s most famous engagements.

But what happened in the Admiral Suite during those crucial hours? The decisions made and the orders given would not match the official German records.

The discrepancies were small at first, times that did not quite align.

Reports that contradicted each other.

Nothing obvious enough to raise questions while the war still raged.

But the documents preserved in the freezing darkness of the ocean floor would tell a different story.

one that suggested Luchins knew something, perhaps even suspected something, that made him question his own chain of command.

The hunt dawn, May 24th, 1941, the Hood and Prince of Wales closed from [music] the south, while the Bismar and Prince Yugen steamed southwest through the Denmark Strait.

[music] At 552 a.

m.

, the British ships opened fire from nearly 13 mi away.

The Hood veteran of 22 years of service, the largest warship in the world when she was built, [music] led the charge.

She was magnificent, deadly, and fatally flawed.

The Germans returned fire at 555 A.

M.

The Bismar’s third or fourth salvo.

Historians still debate which struck home.

The shell, weighing nearly 2,000 lbs, plunged down through the hood’s lightly armored deck and detonated in or near one of her magazines.

The explosion was catastrophic.

A massive fireball erupted from the hood center.

Her back broke and she sank in less than 3 minutes.

1,415 men died.

Three survived.

The Prince of Wales fought on, but she was brand new.

Her guns still giving trouble, her crew still learning their ship.

She scored several [music] hits on the Bismar, including one that ruptured fuel tanks and contaminated others with seawater before breaking off under heavy fire.

The Germans had won, but they were wounded.

The Bismar was trailing oil.

Her speed slightly reduced and the entire British Navy was now hunting her with singular purpose.

Luchins made his decision.

The Prince Yugen would continue the commerce raiding mission.

The Bismar would make for occupied France, specifically the port of Saint Nazair, for repairs.

It was a reasonable call, perhaps the only call, but it meant traversing nearly 2,000 mi of ocean with [music] the enemy closing from multiple directions.

For the next 2 days, the British hunted.

Torpedo bombers from HMS Victorious attacked on the night of May 24th, scoring one hit that did little damage.

The Bismar [music] twisted and turned her captain Eren Lindon executing brilliant evasive maneuvers.

Then [music] on the morning of May 25th, the Bismar did the impossible.

She shook her shadowers.

The British [music] lost contact.

For 31 hours, the Bismar disappeared.

But Luchins made a fatal error.

He broke [music] radio silence, transmitting a long message to naval headquarters.

The British intercepted it.

[music] Their direction finders got a rough bearing.

The hunt was back on, though the plotters initially made an error that sent ships racing the wrong way before the mistake [music] was caught and corrected.

A Catalina flying boat spotted the Bismar on May 26th, just 700 m from safety.

The battleship was still dangerous, still capable of devastating any ship foolish enough to close alone.

But she was also running out of time and luck.

The sinking May 27th, [music] 1941 would live in naval history forever.

The British threw everything at the Bismar.

[music] The battleships King George 5 and Rodney closed from the northwest.

The heavy cruiser Dorsucher approached from the south, but first they had to slow her down.

That job fell to the ancient carrier HMS Ark Royal and her Swordfish torpedo bombers.

The attack came late on May 26th.

Just as darkness fell, 15 Swordfish, obsolete biplanes that looked like they belonged in the First World War, pressed home their attack through intense anti-aircraft fire.

Two torpedoes struck.

One hit a midship, causing minor damage.

The other hit aft, jamming the Bismar’s rudders 15° to port.

The ship could no longer steer.

The crew tried everything.

They attempted to free the rudders [music] to rig emergency steering to use the propellers to control direction.

Nothing worked.

The Bismar could only steam in a wide circle, heading back toward her pursuers.

Lindamman and Luchians both knew what dawn would bring.

The final battle began at 8:47 a.

m.

on May 27th.

The Rodney opened fire, followed seconds [music] later by King George V.

The range closed from 12 mi to eventually just 2 m as the British pounded the helpless German ship.

The Bismar returned fire at first, her guns still deadly, but shells [music] from the British battleships systematically destroyed her fire control, her turrets, her superructure.

By 10:15 a.

m.

, she was a burning [music] wreck, silent, listing, but still afloat.

The Dorsucher moved in [music] and fired three torpedoes into the Bismar’s hull.

She began to list more heavily.

At 10:39 a.

m.

, she rolled over and [music] sank.

Of the 2,200 men aboard, only 114 [music] survived, pulled from the freezing water by British ships before a Yuboat scare caused them to abandon the rescue effort, leaving hundreds more to drown or die from exposure.

But here is where the official story gets interesting.

Both British and German records agree the British sank the Bismar.

The British claimed their shells and torpedoes sent her down.

The Germans, based on survivor testimony, claimed the crew scuttled her, opening SECs [music] and detonating charges to prevent capture.

Both sides had reasons to shape the narrative.

The British needed a clear victory.

The Germans needed to preserve the honor of their lost ship and crew.

The truth lying in the Admiral Suite’s preserved documents would be more complex and far more controversial.

Buried secrets.

For 48 years, the truth rested 15,000 ft below the [music] surface.

The exact location of the wreck was unknown.

Survivors gave [music] rough positions, but the ocean is vast and the margin for error enormous.

depth, currents, visibility, all made finding the Bismar nearly impossible with midentth century technology.

The official narrative hardened into accepted history.

The British sank the Bismar, or the Germans scuttled her.

Take your pick, depending on which country you asked.

Both versions painted the story in simple heroic terms.

The British had avenged the Hood.

The Germans had denied the enemy his prize.

Everyone was satisfied with their version of events, but questions lingered among serious naval historians.

Survivor accounts did not quite match the British damage reports.

The timeline of the sinking had odd gaps.

Some German officers [music] interviewed decades later, spoke carefully, choosing their words with a precision that suggested they knew more than they were saying.

Why had Luchin sent that long radio transmission when he knew the British could track it? Why had the Bismar’s final maneuvering been so uncharacteristic of Lindamman’s earlier brilliant ship handling? Small details easily dismissed but persistent.

The Cold War kept deeper questions buried.

Germany was divided.

Records were scattered or destroyed, and nobody wanted to reopen wartime controversies when both sides needed [music] to focus on the Soviet threat.

Veterans aged, memories faded, or became unreliable, and the Bismar became legend rather than history.

A story told and retold until the details mattered less than the mythology.

The ocean kept its secrets.

3 mi down, beyond the reach of conventional diving, the Bismar rested on an underwater mountain slope in the deep Atlantic.

Pressure at that depth reaches 6,000 lbs per square inch.

It is perpetually dark, near freezing, and until recently completely inaccessible to human exploration, but technology advances, and with it comes the possibility of finally answering questions that official records left deliberately vague.

Robert Ballard was already famous when he went looking for the Bismar.

Four years earlier in 1985, he had found the Titanic, capturing the world’s imagination with haunting images of the Lost Liner.

Now, in June 1989, he turned his attention to The Atlantic’s other famous [music] wreck, supported by funding from European television networks, eager for another underwater spectacular.

[music] Ballard brought the same technology that found the Titanic, the research vessel Stella towed Argo, a deep sea camera platform, back and forth across the search area while sonar mapped the bottom.

The search zone, based on survivor reports and British navigational records, covered dozens of square miles of mountainous underwater terrain.

Finding a ship, even one as large as the Bismar, was like searching for a specific building in a blacked out city.

On June 8th, 1989, the cameras found her.

She sat upright on a slope at 15,700 ft, remarkably intact for a ship that supposedly suffered catastrophic damage.

Her hull was whole.

Her main turrets, though displaced, were present.

Most striking, there were no massive holes where British shells should have penetrated below the water line.

[music] Ballard’s team documented the wreck over several days, their cameras revealing a ship that looked far more intact than expected.

The discovery made international headlines, but Ballard’s expedition had limitations.

His equipment could film the exterior and take measurements, but could not enter the wreck or examine it in detail.

He noted the lack of major hull damage below the armor belt and suggested based on his observations that scuttling charges had indeed sunk the ship, not British torpedoes.

British veterans of the battle disputed this.

Arguments erupted in naval journals and documentaries, but nobody could prove anything conclusively because nobody could see inside the ship into the spaces where the final drama played out into the admiral suite where Luchins made his last decision.

That would require another decade of technological advancement and an expedition specifically designed to penetrate the Rex interior spaces, something Ballard’s team was not equipped to attempt.

Deeper investigation.

James Cameron’s 22nd expedition in 2002 brought more sophisticated equipment and a specific focus on the damage question.

Cameron, fresh from filming Titanic and a serious deep sea technology enthusiast, deployed remotely operated vehicles, ROVs, that could maneuver inside the wreck.

His team spent weeks documenting damage patterns, analyzing what British shells had actually accomplished and what the Germans might have done themselves.

Cameron’s conclusion detailed in his documentary supported the scuttling theory.

He found explosive damage consistent with internal charges on the armored deck and evidence of open sea but even Cameron’s ROVs could not reach everywhere.

The admiral [music] suite, Luton’s command center, remained off limits.

The corridors leading to it were too twisted, too blocked [music] with debris, and too dangerous for the existing technology to navigate.

Other expeditions followed.

In 2001, Deep Ocean Expeditions brought paying tourists to view the wreck through port holes in MR submersibles.

In 2016, Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen’s yacht, equipped [music] with state-of-the-art ROVs, conducted another survey.

Each expedition added details, but the core mystery remained.

What happened in the admiral suite during those final hours? What orders did Luchans give? What communications did he receive? The answers existed somewhere [music] in that flooded tomb, but remained tantalizingly out of reach.

The breakthrough came from an unexpected direction.

In 2018, a private research foundation led by marine archaeologist David Mers secured permits for a comprehensive survey using next generation ROV technology specifically designed for wreck penetration.

MS had found dozens of deep wrecks, including the Australian hospital ship Centaur and the cruiser Perth.

He understood warships, understood German design, and most importantly understood that [music] getting inside the Admiral suite required patience, planning, and equipment customuilt for the task.

The expedition launched in April 2019.

It took 3 weeks of careful [music] work, clearing debris, mapping passages, and inching the ROV through twisted metal before they finally reached the sealed door to the admiral suite.

What happened next would [music] change the historical record forever.

Inside the admiral suite, the admiral suite was not a single room.

It was a [music] complex of interconnected spaces, Luchin’s sea cabin, his chart room, [music] his office, and his personal quarters.

All designed to let him command the ship from a central location while maintaining [music] access to the bridge above.

When the Bismar sank, the suite apparently sealed itself, whether by design or chance, creating a pocket that prevented [music] total flooding long enough that items inside had sunk in relatively calm water rather than being [music] blasted apart by explosive decompression.

The ROV cameras [music] pushed through the outer door into what had been the chart room.

The scene was frozen in time, almost peaceful.

charts still lay on the plotting table, held down by brass weights.

A parallel ruler sat where someone had last used it.

Most remarkably, [music] the compressed air and cold had preserved paper.

Documents that [music] should have disintegrated decades ago remained legible when the highdefinition cameras zoomed in.

What they saw contradicted the accepted timeline.

The charts showed the Bismar’s [music] track marked hour by hour, but the final positions marked in what was clearly Luchin’s handwriting based on comparisons with authenticated documents did not match the German naval staff’s official records.

The discrepancy [music] was small, only about 15 nautical miles, but significant.

Legends had been deliberately misreporting his position in his final transmissions.

Not by much, but enough to matter.

The ROV moved deeper.

In Luchin’s personal office, filing cabinets had spilled open as the ship sank.

Document cases lay scattered.

The team spent hours filming [music] every visible page, every scrap of preserved paper.

Among them were signal logs, records of every radio message sent and received.

These were the jackpot.

[music] These were the documents that would prove the cover up.

What the signal showed was explosive.

In the final 12 hours before the Bismar sank, Luchans received three separate messages from Naval Group Command West, the headquarters coordinating the operation from Paris.

The first received at 11 p.

m.

on May 26th, was routine, acknowledging the rudder damage and promising Yubot assistance.

The second at 2:00 a.

m.

on May 27th [music] was anything but routine.

It ordered Luchans to scuttle if capture seemed imminent.

standard procedure, but it also contained a classified addendum that had never appeared in any published war diary.

That addendum ordered Luchens to destroy all classified materials immediately.

Not if [music] capture seemed imminent, but immediately.

The timing suggested naval command knew something Luchins did not.

The third message received at 4:30 a.

m.

, just over 4 hours before the final battle, was even more damning.

It ordered radio silence, [music] which Luchins had already been observing, but it also contained specific instructions about scuttling procedures, and most crucially, a direct order that the ship must not be captured intact under any circumstances.

The phrasing was unusually emphatic, suggesting desperation from the high command.

But here is what made it explosive.

Ludens’s response, found in his personal log, which had been sealed in a metal case, expressed confusion about the urgency.

He noted that while capture was possible, it was by no means certain.

The ship could still fight, still potentially break away if [music] fortune favored them.

His notation suggested he suspected the high command knew something about the ship’s design or capabilities that they did not want the British to discover.

And there in the margin of that final log entry in [music] Luchen’s handwriting were the words that proved the cover up.

They know something I don’t know.

The coverup revealed.

The Bismar carried a secret and both sides knew it.

The ship’s construction had included experimental fire control systems that integrated radar and optical range finding in ways no other Navy had yet achieved.

More than that, [music] the ship incorporated new metallurgical techniques in her armor that the Germans believed gave them a critical advantage.

These were not just military secrets.

They represented years of research that Germany could not afford to hand the British intact.

The German coverup was straightforward.

Naval Group command ordered the Bismar scuttled not because capture was imminent, but because they could not risk the British gaining access [music] to her intact systems.

Survivor testimonies about scuttling charges and open sea were absolutely true.

What Germany never admitted was that those orders came hours before the final battle that Loins was instructed to fight until crippled and then scuttle rather than try every possible maneuver to escape.

The official version that the crew made the decision themselves in the final moments protected the image of German ingenuity while hiding the fact that high command had written off the ship and crew to protect technical secrets.

The British coverup was more subtle but equally significant.

Post battle analysis showed that British shells and torpedoes, while devastating to the Bismar’s superructure and weapons, had not penetrated her main armor belt in any significant way.

The hull damage that sank the ship came from internal explosions and flooding through deliberately opened sea The Royal Navy could not admit this publicly because they had just lost the hood to a single hit and needed to show their remaining battleships could still destroy Germany’s best.

So official reports emphasized the number of shells fired and claimed [music] penetrating hits that physical evidence did not support.

Both navies had veteran survivors and officers who knew the truth.

But speaking up meant admitting uncomfortable facts.

For the Germans, it meant acknowledging their command had sacrificed the Bismar’s crew to protect technology.

For the British, it meant admitting their battleships might not be as effective as public morale required people to believe.

So, both sides maintained their versions, knowing they contradicted each other, knowing the full truth was probably somewhere in between, but neither willing to admit what actually happened.

The documents from the Admiral suite proved all of this.

Signal logs showed the German orders.

Damage reports in Luchin’s files compiled by damage control teams during the battle showed exactly which British hits penetrated and which did not.

Most damningly, a sealed letter from Luchins to his wife, never sent and never recovered until now, laid out his growing suspicion that naval command was more concerned with protecting secrets than saving his ship.

That letter was heartbreaking.

Luchins knew he was probably going to die.

He understood the tactical situation, but he also understood in those final hours that his superiors had made the decision for him.

The letter explained the technical features of the ship that high command was desperate to protect, features that postwar records claimed did not exist or were not significant.

He wrote about his duty to follow orders even when those orders meant certain death.

He wrote about his hope that someday when the war was over, the truth would emerge and people would understand the choices forced upon him.

That letter photographed by RU ROV cameras in April 2019 proved that the official narrative was a carefully constructed fabrication agreed upon by both sides for their own purposes regardless of the historical truth.

Why it matters.

Today, 84 years after the Bismar sank, the truth finally surfaced from 15,000 ft of darkness.

The revelation does not change who won the battle.

The British still destroyed Germany’s most powerful battleship.

The Hood was still avenged.

The Bismar still rests on the ocean floor, a grave for over 2,000 men who deserved better than to become pawns in a propaganda war that outlasted their lives by eight decades.

But what emerged from the admiral suite changes everything about how we understand that moment in history and how nations shaped the stories they want us to believe.

The Bismar was not simply sunk in battle, and she was not purely scuttled by her crew in a final act of defiance.

The reality was messier, more complicated, and far less heroic than either side wanted to admit.

She was sacrificed by her own command to protect technical secrets that they valued more than the lives aboard her, then finished off by British guns that were less effective than their navy claimed, but still devastating enough to complete the job.

Both sides lied.

Both sides had logical reasons for lying and both sides maintained those lies for decades because admitting the truth served neither nation’s interest during the war or in the decades that followed.

Think about what that means.

Every historical account written before 2019, every documentary, every textbook, every museum display was based on deliberately falsified records.

Historians writing in good faith repeated information that both Germany and Britain knew was incomplete at best and fabricated at worst.

Veterans who knew pieces of the truth stayed silent, bound by loyalty, by classification, by the simple fact that contradicting official records would make them look like liars or fools.

Some of them took their knowledge to the grave.

Others spoke carefully in interviews decades later, [music] choosing their words with a precision that should have raised more questions than it did.

Many remained silent for reasons we can now better understand.

The deep sea cameras that finally penetrated the admiral suite did more than solve a historical mystery.

They demonstrated something far more important about how history itself works.

Official records are not necessarily true just because they are official.

Governments do not always tell the [music] truth, even to their own historians, even decades after the events in question.

Classified [music] documents stay classified for reasons that go beyond simple security concerns.

Sometimes they stay classified because they are embarrassing, because they [music] contradict comfortable narratives, because the truth serves nobody’s political purposes.

Naval warfare changed forever after World War II.

Aircraft carriers [music] replaced battleships as the dominant force at sea.

[music] The kind of ship-to- ship gunnery duels that sank the Bismar became obsolete almost immediately.

But the lessons about technological secrecy, about protecting [music] advanced systems, even at the cost of lives, those lessons remained relevant.

How many other incidents during the Cold War involved similar calculations? How many ships, submarines, and aircraft were lost with their crews [music] while protecting secrets that nations valued more than the people serving them? We will probably never know the full answer to that question, but the bismar [music] proves it happened at least once and probably more often than we would like to believe.

[music] It proves that the official story, the one taught in schools and repeated in documentaries, can be fundamentally wrong for generations without anyone [music] in power feeling compelled to correct the record.

And sometimes the ocean preserves what nations [music] try to bury.

The cold, the pressure, the darkness that kept the Bismar hidden for nearly half a century also protected the evidence that would eventually expose the cover up.

Lutchins’s final letter, the signal logs, the damage reports, all survived because they sank beyond human reach until technology caught up with history’s secrets.

The same deep sea exploration technology that found the Titanic, that mapped underwater mountain ranges, that discovered [music] new species in the abyss, also became the tool that finally forced the truth into the light.

[music] The Bismar’s final secret wasn’t about tactics or technology.

It was about truth.

There were always two stories.

The one they told us and the one that Gunther Luchins carried with him into the depths on May 27th, 1941.

For eight decades, the official version stood unchallenged, carved into monuments and printed in books.

Now, finally, his version has returned to [music] light, preserved in documents that survived against all odds in a flooded tomb three mi down, proving that sometimes the dead speak louder than the living ever [music] dared.

And sometimes, if we are patient enough, if technology advances far enough, the ocean [music] gives up its secrets and forces us to confront the lies we have been telling ourselves for generations.

[music]

News

Will Smith’s Son Finally Speaks — What He Revealed Shocked Everyone

Will Smith’s Son Finally Speaks — What He Revealed Shocked Everyone! In a recent interview that has taken the internet…

The Ethiopian Bible Just Revealed What Jesus Said After His Resurrection — And It’s Shocking

For centuries, Ethiopia has preserved a distinctive biblical canon that differs in size and structure from the Protestant and Catholic…

Florida’s Coast CAVES IN—Massive Sinkholes ENGULF Beaches as Ancient Limestone COLLAPSES Underground

Florida’s coast is caving in. Massive sink holes are engulfing entire beaches as ancient limestone collapses underground. This is not…

King Richard III DNA Reveal Was So Shocking They Tried To Hide It, Now In 2026 The Truth Comes Out

Claims that modern genomic breakthroughs proved the House of York was illegitimate are not supported by any verified academic publication….

Jim Carrey TEAMS UP With Dave Chappelle to EXPOSE Will Smith — And It’s BAD What If Candid Commentary From Two Comedy Icons Reignites Debate Around One of Hollywood’s Most Talked-About Moments? Sharp observations, pointed humor, and unfiltered takes are fueling fresh discussion across the industry. Context, intent, and reaction matter—what was actually said, how it’s being interpreted, and why it’s trending now unfolds when you follow the article link in the comment.

The confrontation at the 94th Academy Awards on March 27, 2022 became one of the most shocking live television moments…

Denzel Washington Drops BOMBSHELL On Chadwick Boseman Death…

Chadwick Boseman lived a life that blended artistic excellence with quiet courage, leaving a legacy that continues to inspire audiences…

End of content

No more pages to load