For much of Christian history, the story of faith has been told through a Western lens shaped by empire, councils, and power.

Yet beyond Rome and Europe, in the highlands of Africa, Ethiopia preserved a version of Christianity that developed outside imperial control.

Its scriptures, images, and theology challenge many assumptions modern believers take for granted, raising unsettling questions about how the stories of Jesus, evil, and Lucifer were formed, edited, and transmitted across centuries.

Ethiopia occupies a unique place in Christian memory.

According to ancient tradition, Christianity reached the kingdom in the first century through an Ethiopian court official baptized by the apostle Philip.

Long before Rome legalized Christianity or crowned emperors under the cross, Ethiopia had already woven the faith into its national identity.

This early and independent conversion meant that Ethiopian Christianity did not inherit its beliefs from Europe.

Instead, it grew from Near Eastern roots and developed in relative isolation, protected by geography, culture, and a strong sense of sacred lineage.

That isolation would prove decisive.

One of the most striking features of Ethiopian Christianity is its canon of scripture.

While most Western Christians read a Bible of sixty-six books, the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church preserves a canon of eighty-one.

Among these are texts long excluded or forgotten in the West, including the Book of Enoch and the Book of Jubilees.

These writings were once known to early Jewish and Christian communities and are even echoed or quoted in the New Testament, yet they were later set aside as the church in Europe narrowed its canon.

Ethiopia did not follow that reduction.

It kept what it had received.

The survival of these texts matters because they present a vision of reality that is broader and more complex than later Western theology often allows.

The Book of Enoch, for example, describes a world alive with cosmic conflict: angels who rebel, heavenly courts, and divine judgments that predate human history.

Jubilees retells Genesis with an emphasis on sacred time, angelic order, and spiritual warfare unfolding behind the visible world.

Together, these texts portray evil not as a simple afterthought, but as a deep and ancient tension woven into creation itself.

This wider scriptural world reshapes how Ethiopia understands figures like Lucifer.

In Western Christianity, Lucifer is typically imagined as a once-perfect angel who rebelled out of pride and was instantly cast from heaven, becoming the devil.

This dramatic narrative, reinforced by medieval poetry and art, feels central to Christian belief.

Yet its biblical foundations are surprisingly thin.

The passages most often cited, in Isaiah and Ezekiel, were originally poetic judgments against earthly kings, not clear accounts of a cosmic angelic revolt.

Over time, interpretation filled in the gaps, transforming metaphor into myth.

Ethiopian tradition, informed by its broader canon, preserves a more ambiguous and unsettling picture.

Lucifer is not simply a fallen rebel removed from heaven in a single moment.

Instead, he appears as an accuser and tester, a being permitted for a time to operate within the limits set by God.

This echoes the figure seen in the Book of Job, where the accuser stands in the heavenly court, challenging the sincerity of human faith.

Evil, in this vision, is real and dangerous, but it is not sovereign.

It exists under constraint, allowed as part of a testing that reveals what lies hidden in the human heart.

This understanding transforms the idea of spiritual struggle.

Rather than a universe divided between two equal powers locked in endless war, Ethiopia’s theology presents a cosmic courtroom.

God remains the ultimate judge, humanity stands under trial, and the accuser’s role is to question, pressure, and expose.

Lucifer accuses, but he does not decide the verdict.

His presence serves, unwillingly, to refine faith rather than to overthrow divine authority.

Such a view removes fear as a tool of control and replaces it with responsibility: endurance, faithfulness, and trust become central virtues.

It is not difficult to see why this perspective troubled imperial Christianity.

As the Roman Empire adopted the faith, theology became intertwined with governance.

Clear hierarchies were favored, obedience was emphasized, and rebellion was framed as satanic.

A simple story of Lucifer’s total fall supported this worldview: rebellion leads only to ruin.

Ethiopia’s more nuanced vision, by contrast, undermined the logic of empire.

If evil itself operates only by permission, then no earthly ruler can claim divine authority beyond question.

Faith becomes allegiance to God, not submission to power.

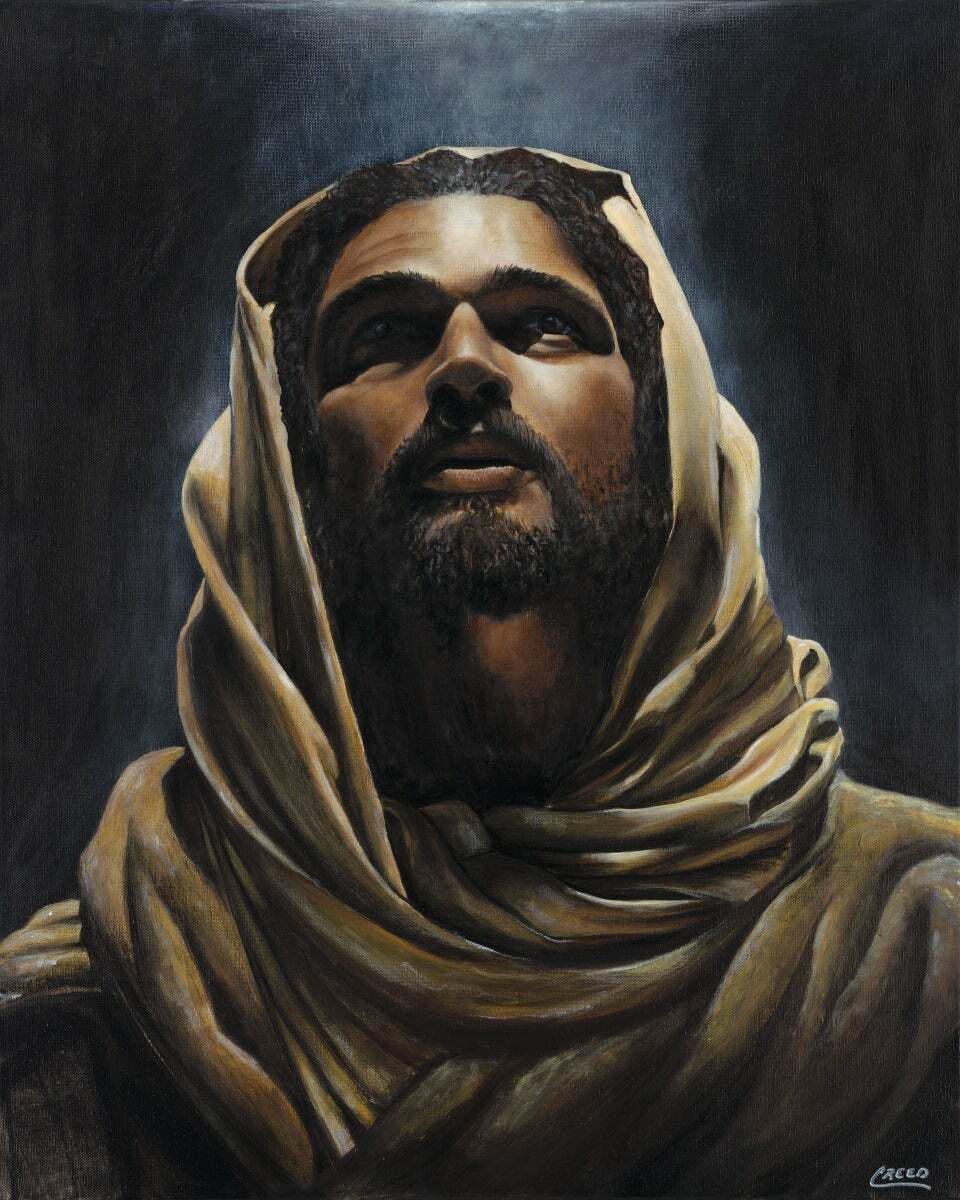

Equally disruptive is Ethiopia’s image of Christ.

In Western art, Jesus gradually took on the features of European rulers: pale skin, regal posture, imperial calm.

This transformation coincided with Christianity’s rise as the religion of empire.

In Ethiopia, however, Christ was never recast to resemble Caesar.

Ancient icons, murals, and manuscripts consistently portray Jesus with dark skin and features familiar to African believers.

This was not a political statement in the modern sense; it was a theological instinct.

God was understood to dwell among the people, not above them.

The difference is profound.

An imperial Christ legitimizes authority, conquest, and hierarchy.

A Christ who resembles the oppressed proclaims solidarity, suffering, and hope.

Ethiopia’s black Christ reinforced a gospel centered on endurance rather than domination.

Salvation was not tied to empire or expansion, but to covenant, memory, and faithfulness across generations.

This vision would later resonate powerfully among enslaved and marginalized peoples, for whom a distant, imperial savior offered little comfort.

The contrast between these traditions raises difficult questions.

If the image of Christ could be reshaped to serve political power, could his message also have been softened or redirected? If certain scriptures were removed because they complicated authority, what truths were lost in the process? Ethiopia’s witness suggests that Western Christianity inherited not the whole story, but a carefully managed version of it.

This does not mean that Western Christianity is false, nor that Ethiopia possesses a secret gospel that invalidates all others.

Rather, it reveals that Christian history is more diverse, contested, and human than official narratives often admit.

Theology develops within context.

Power influences interpretation.

Decisions made in councils and courts echo for centuries.

Ethiopia’s endurance offers a counterexample.

Never fully colonized, never absorbed into Roman or Byzantine control, it stood at a crossroads without surrendering its identity.

Its rock-hewn churches, carved downward into living stone, symbolize a faith rooted rather than elevated.

Its crosses, intricate and interwoven, emphasize continuity rather than conquest.

Its scriptures, preserved through isolation and devotion, remind the world that memory can be an act of resistance.

In this light, Ethiopia is not merely an exotic footnote in Christian history.

It is a mirror held up to the global church.

It asks whether faith has been shaped more by empire than by apostles, more by power than by endurance.

It challenges believers to reconsider inherited images of Christ and inherited stories of evil, not to discard them, but to see them more clearly.

The story Ethiopia tells is ultimately not about secret knowledge or forbidden myths.

It is about humility before mystery.

Evil is not easily explained.

Faith is not easily proven.

God’s purposes unfold through trial as much as triumph.

Lucifer’s presence tests, Christ’s presence redeems, and humanity stands between accusation and grace.

In a world still marked by power struggles, inequality, and fear, Ethiopia’s ancient Christianity speaks with quiet relevance.

It reminds us that truth does not always survive where voices are loudest, but where memory is guarded most carefully.

It suggests that faith shaped by endurance may outlast faith shaped by empire.

And it invites a reconsideration of what it truly means to follow Christ, not as a symbol of dominance, but as a companion in suffering, testing, and hope.

News

Black CEO Denied First Class Seat – 30 Minutes Later, He Fires the Flight Crew

You don’t belong in first class. Nicole snapped, ripping a perfectly valid boarding pass straight down the middle like it…

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 7 Minutes Later, He Fired the Entire Branch Staff

You think someone like you has a million dollars just sitting in an account here? Prove it or get out….

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 10 Minutes Later, She Fires the Entire Branch Team ff

You need to leave. This lounge is for real clients. Lisa Newman didn’t even blink when she said it. Her…

Black Boy Kicked Out of First Class — 15 Minutes Later, His CEO Dad Arrived, Everything Changed

Get out of that seat now. You’re making the other passengers uncomfortable. The words rang out loud and clear, echoing…

She Walks 20 miles To Work Everyday Until Her Billionaire Boss Followed Her

The Unseen Journey: A Woman’s 20-Mile Walk to Work That Changed a Billionaire’s Life In a world often defined by…

UNDERCOVER BILLIONAIRE ORDERS COFFEE sa

In the fast-paced world of business, where wealth and power often dictate the rules, stories of unexpected humility and courage…

End of content

No more pages to load