For decades, one branch of a notorious family lived in silence, weighed down by a name that carried fear, anger, and suspicion wherever it appeared.

Among them was Johann Schmidt Junior, a man who never chose his place in history but was shaped by it nonetheless.

Born into an ordinary Austrian family, Johann grew up far from power, ideology, or ambition.

Yet his blood connection to Adolf Hitler followed him throughout his life, marking him as guilty by association in the eyes of many.

As he reached old age, Johann decided that silence no longer served truth or memory.

His recollections do not seek to excuse crimes or soften responsibility.

Instead, they offer a human perspective on how history damages not only its victims, but also those trapped in the shadow of its perpetrators.

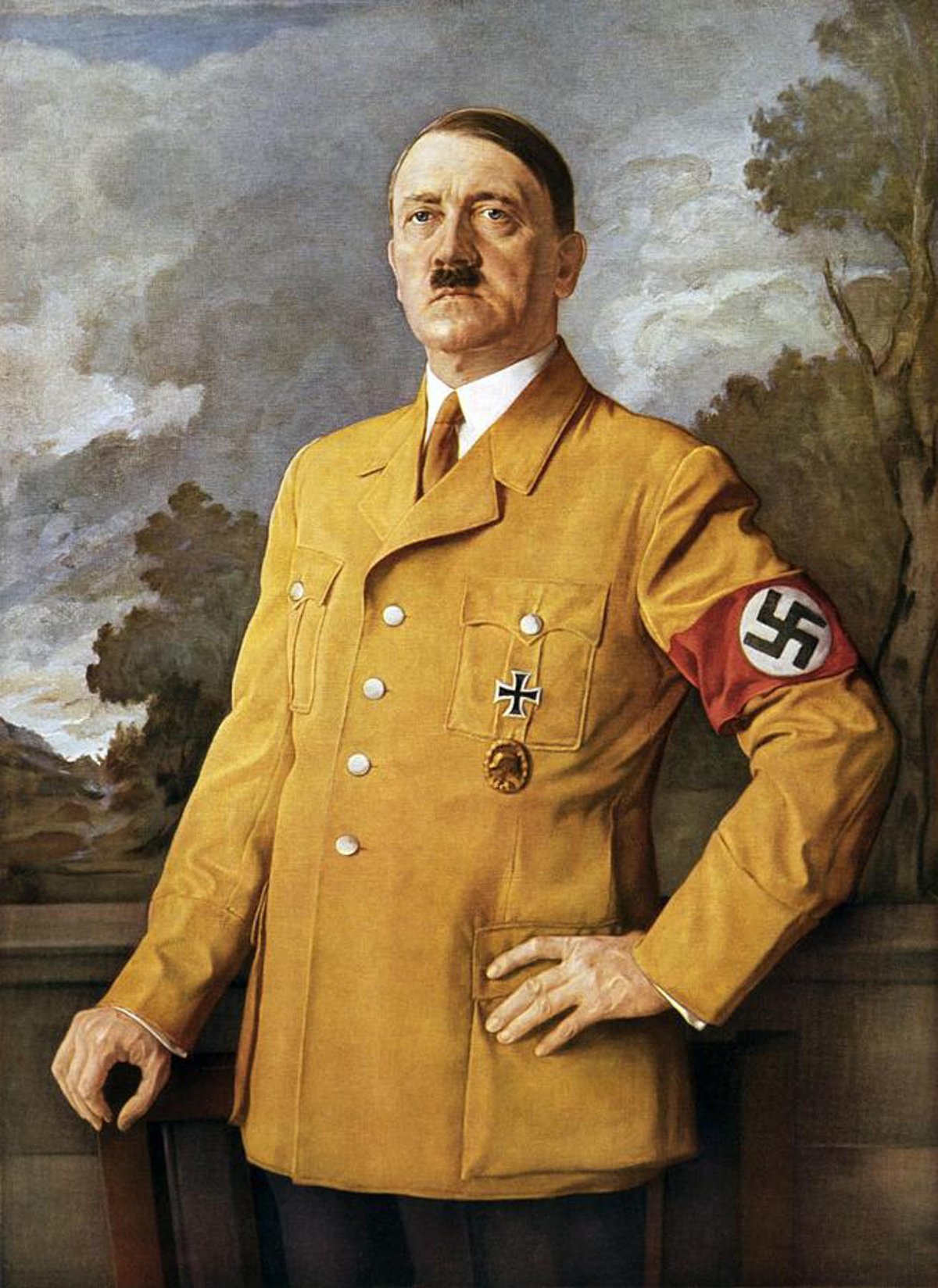

Adolf Hitler is remembered as one of the most destructive figures of the twentieth century.

His name is synonymous with war, genocide, and unimaginable suffering.

Yet before he became the leader of Nazi Germany, he was an obscure young man shaped by personal failure, rigid family discipline, and resentment.

Born in eighteen eighty nine in Braunau am Inn, Austria, Hitler grew up under a harsh father who valued obedience above affection.

His mother provided warmth and devotion, and her influence remained the only consistent emotional bond in his early life.

As a youth, Hitler dreamed of becoming an artist.

He applied twice to the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna and was rejected both times.

Those rejections deepened his bitterness and pushed him toward radical beliefs he absorbed from the political climate of the city.

During his years in Vienna, Hitler struggled with poverty and isolation.

He read inflammatory newspapers and listened to extremist rhetoric in cafes and meeting halls.

Over time, prejudice hardened into conviction.

When the First World War began, Hitler joined the German army as a messenger.

He was not a commanding officer, but he served with discipline and received medals for bravery.

The defeat of Germany in nineteen eighteen shattered his sense of purpose.

He viewed the loss as humiliation and betrayal, and this grievance became the foundation of his political identity.

In postwar Germany, economic collapse and social unrest created fertile ground for radical movements.

Hitler joined a small nationalist group that would later become the Nazi Party.

His speeches resonated with crowds because they echoed public anger and despair.

After a failed attempt to seize power in nineteen twenty three, Hitler was imprisoned.

There he wrote Mein Kampf, outlining his worldview and ambitions.

After his release, he pursued power through legal channels.

By nineteen thirty three, he was appointed chancellor.

Within months, democratic institutions were dismantled, opposition silenced, and Hitler consolidated authority under the title of Führer.

While the world watched these developments with concern and hesitation, members of the extended Hitler family experienced a different reality.

For them, Adolf Hitler was not a distant political figure but a relative whose presence brought tension and unease.

Johann Schmidt Junior belonged to this extended circle.

His father and Hitler were cousins, which placed Johann within the family network even if personal contact was limited.

According to family memory, Hitler was never warm or playful at gatherings.

He observed more than he spoke, creating discomfort rather than familiarity.

These impressions remained vivid for those who encountered him before his rise to power.

Inside the Hitler household, relationships were marked by control and distance.

Alois Hitler ruled the family with strict discipline, while Klara Hitler offered unconditional care.

Adolf Hitler became increasingly withdrawn as he grew older, limiting emotional connections even with siblings.

His sister Paula lived quietly and avoided public attention throughout her life.

His half sister Angela later managed his household, but even she was eventually pushed aside.

The death of Angela daughter Geli, under mysterious circumstances, deepened the atmosphere of silence and fear within the family.

After that event, Hitler cut ties more decisively, forcing relatives into obscurity and discouraging any public association.

Johann Schmidt Junior witnessed these patterns indirectly.

He saw how relatives avoided speaking about certain names or events, how fear replaced familiarity.

As Hitler gained power, family connections became liabilities.

When the Second World War ended in nineteen forty five, the burden of the name became deadly.

Soviet authorities arrested Johann and several relatives, accusing them of collaboration or hidden knowledge.

No evidence was required.

Bloodline alone was sufficient.

Johann was eighteen when he was taken away with his parents and cousins.

They were sent to Soviet labor camps, where conditions were brutal.

Prisoners worked long hours with little food or medical care.

Disease and exhaustion were common.

Over the years, Johann lost nearly his entire family.

His parents died in captivity, as did his cousin Eduard and other relatives.

Johann survived by endurance rather than hope.

In nineteen fifty five, he was unexpectedly released and returned to Austria alone.

His home was gone, his family erased, and his name remained a stigma.

After his release, Johann chose silence.

This decision was shaped by fear learned through experience.

During the war, Nazi policies punished entire families for the actions of individuals.

After the war, similar logic prevailed in occupied territories.

Speaking openly invited suspicion, interrogation, and renewed suffering.

Johann built a modest life and avoided attention.

He did not defend himself publicly or seek sympathy.

Survival meant staying invisible.

The question of family knowledge regarding Nazi crimes has long troubled historians.

The Holocaust was not a single event but a systematic campaign that murdered six million Jews and millions of others deemed undesirable by the regime.

It unfolded through laws, deportations, camps, and mass executions.

Some relatives of Nazi leaders claimed ignorance, while others heard rumors but lacked full understanding.

In Johann case, silence was not an admission of guilt but a shield against further harm.

His trauma came from loss, imprisonment, and inherited blame rather than ideological involvement.

Other relatives faced similar fates.

Maria Schmidt, another cousin, was arrested with her husband and brothers and sent to prison camps.

Interrogations forced confessions that held no factual basis.

She died in custody, as did her husband Ignaz and her brother Eduard.

None of them held political power or military roles.

Their lives ended because of association rather than action.

These stories illustrate how collective punishment extended suffering beyond the original crimes.

In later years, Johann reflected on memories passed down by his father.

One story described a youthful Adolf Hitler dissecting a frog with unsettling calm during a family visit.

Whether this moment held deeper meaning or simply reflected a disturbed personality remains open to interpretation.

Johann shared it not as proof of destiny, but as an example of how unease existed long before history took its course.

As Hitler rose, he distanced himself further from his origins, rejecting his rural roots and hiding family ties that no longer suited his image.

The remaining members of the Hitler family faded quietly after the war.

Paula lived under an assumed name and avoided public life until her death without children.

In the United States, William Patrick Hitler changed his name and raised sons who chose not to continue the family line.

In Austria, other relatives withdrew completely from public view.

There was no formal agreement to end the bloodline, yet each branch made similar choices, guided by shame, fear, or a desire to prevent further association.

Adolf Hitler final days unfolded in a bunker beneath Berlin as Soviet forces closed in.

His regime collapsed, and he ended his life in April nineteen forty five.

His death did not erase the consequences of his actions.

Camps were liberated, survivors emerged, and the full scale of atrocity became known.

For people like Johann Schmidt Junior, the end of the war did not bring relief.

It brought years of imprisonment and a lifetime of silence.

When Johann finally chose to speak, it was not to rewrite history or diminish responsibility.

It was to acknowledge how deeply the actions of one individual can scar generations.

His story reveals that while guilt belongs to those who commit crimes, suffering often spreads far wider.

The Hitler family did not vanish through dramatic endings or public reckonings.

It dissolved slowly, through name changes, childless lives, and deliberate obscurity.

In that quiet disappearance lies a reminder that history leaves marks not only on nations, but on families who must live with its aftermath long after the world moves on.

News

Burke Ramsey Speaks Out: New Insights Into the JonBenét Ramsey Case td

Burke Ramsey Speaks Out: New Insights Into the JonBenét Ramsey Case After more than two decades of silence, Burke Ramsey,…

R. Kelly Released from Jail td

R&B legend R.Kelly has found himself back in the spotlight for all the wrong reasons, as he was recently booked…

The Impact of Victim Shaming: Drea Kelly’s Call for Change td

The Impact of Victim Shaming: Drea Kelly’s Call for Change In recent years, the conversation surrounding sexual abuse and domestic…

Clifton Powell Reveals Woman Lied & Tried To Set Him Up On Movie Set, Saying He Came On To Her td

The Complexities of Truth: Clifton Powell’s Experience on Set In the world of film and television, the intersection of personal…

3 MINUTES AGO: The Tragedy Of Keith Urban Is Beyond Heartbreaking td

The Heartbreaking Journey of Keith Urban: Triumphs and Tribulations Keith Urban, the Australian country music superstar, is often celebrated for…

R. Kelly’s Ex-Wife and Daughter Speak Out About the Allegations Against Him td

The Complex Legacy of R. Kelly: Insights from His Ex-Wife and Daughter R. Kelly, the renowned R&B singer, has long…

End of content

No more pages to load