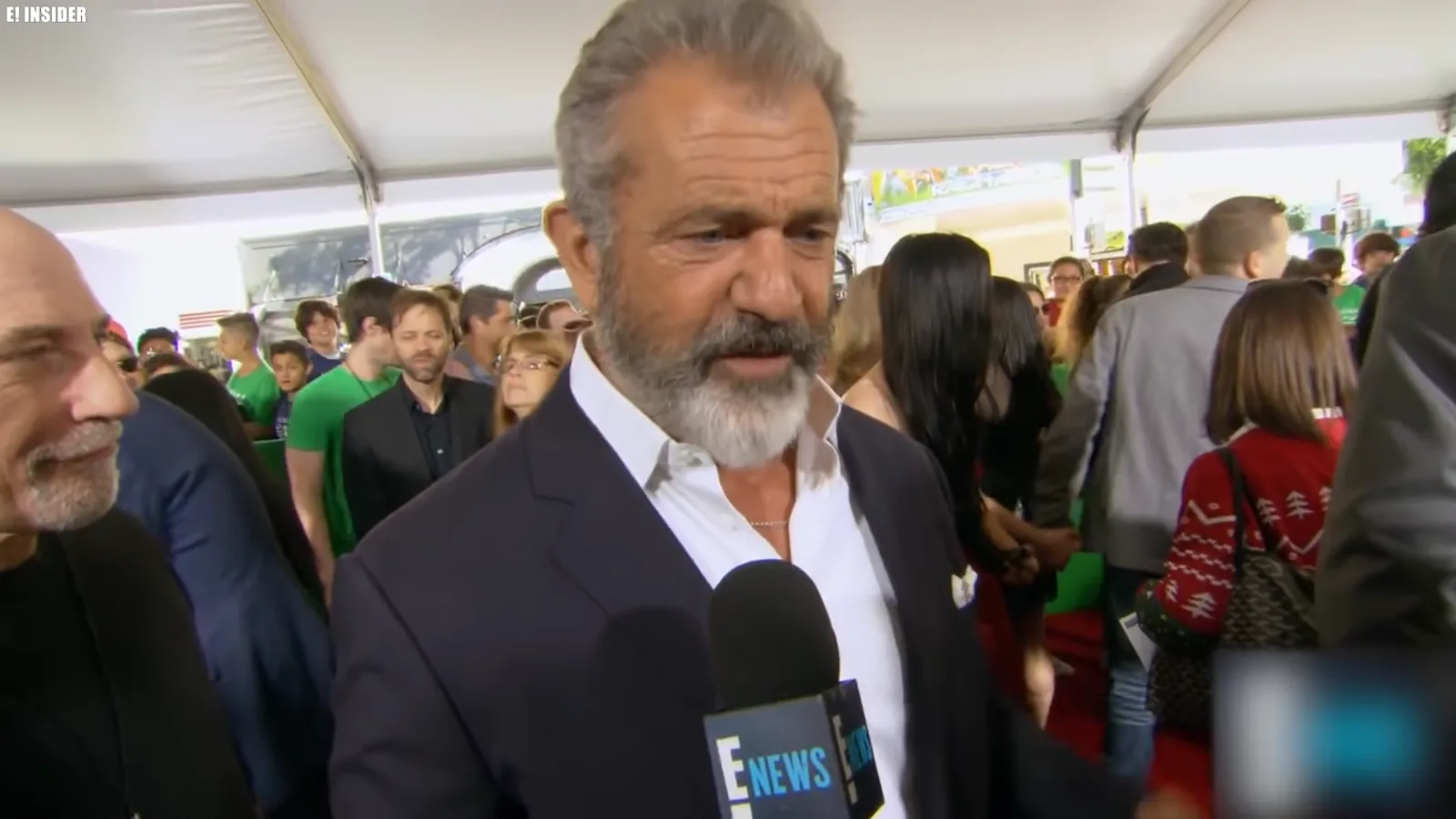

You’re doing a very similar thing that you were doing with the passion of the Christ where this is this is a profound story.

Yes.

When you put something like that together, how do you choose who’s going to be the next Jesus? You use him again.

Caviso.

Yeah.

Before the lightning strikes, before the blacklists, before the screams that weren’t acting, Mel Gibson made a choice that Hollywood begged him not to.

Now, decades later, and nearing the end of his life, he’s finally admitting why this wasn’t just a film.

It was a reckoning.

And what happened behind the scenes.

That’s the part no one’s dared to say out loud until now.

And everybody cheered and they went crazy.

And then about a half an hour later, black smoke came out.

That never in history has that happened that the white smoke came out.

The film Hollywood was afraid to touch.

Hollywood didn’t just hesitate on the Passion of the Christ.

It flinched hard.

By the late 1990s, Mel Gibson was one of the most bankable stars on the planet.

That’s what makes what happened next so strange.

Studio after studio heard the pitch and walked away.

Not because of budgets, not because of scheduling, but because the film itself scared them.

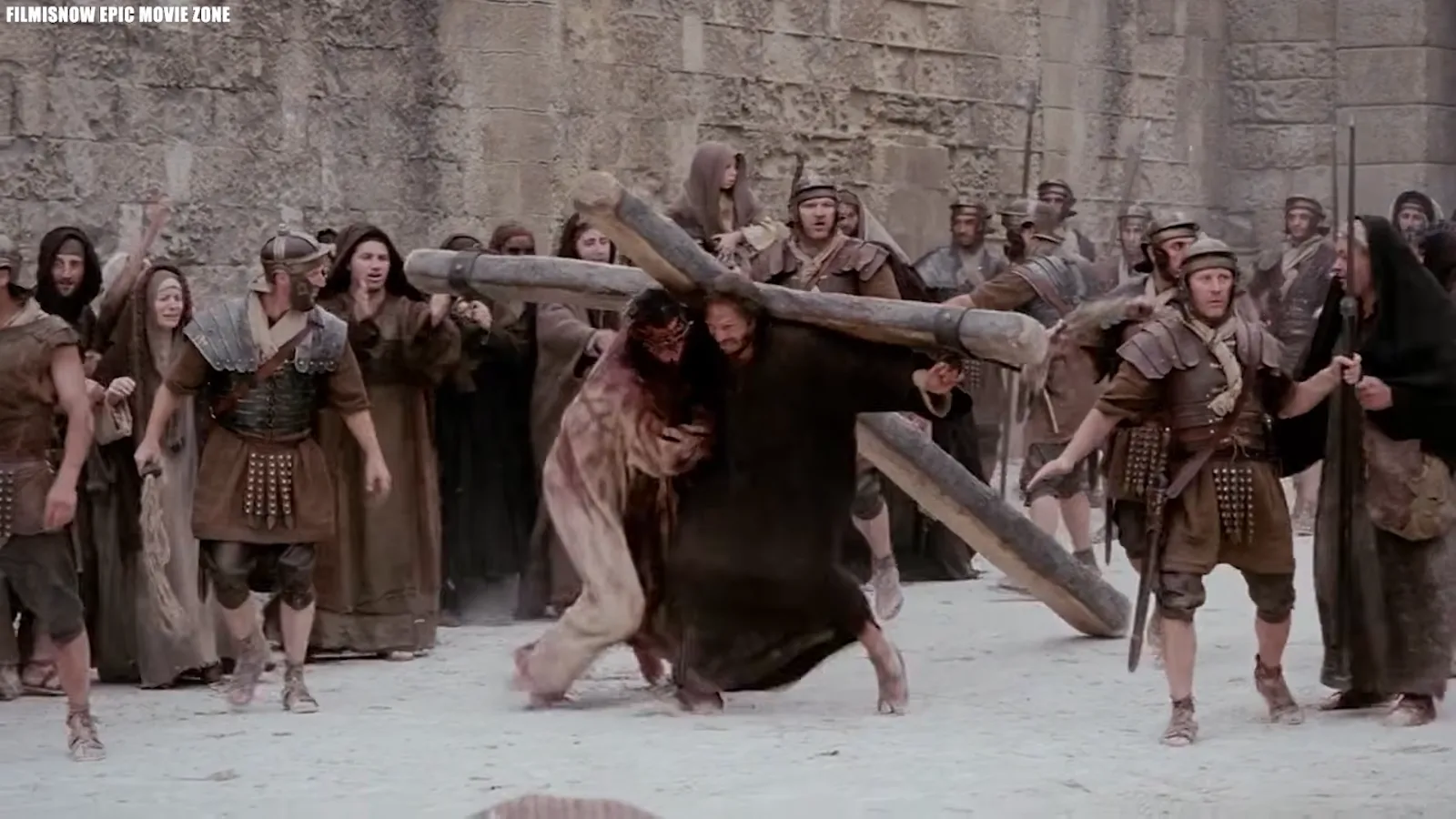

An R-rated religious film spoken entirely in Aramaic and Latin.

No English safety net.

No softened violence, no heroic gloss.

Executives reportedly told Gibson audiences wouldn’t sit through subtitles, wouldn’t tolerate brutality, and definitely wouldn’t embrace a story that refused to modernize itself.

In Hollywood terms, it was unmarketable.

In Mel’s words, it was non-negotiable.

Here’s the part people forget.

Gibson wasn’t chasing controversy.

He was chasing accuracy.

He insisted Jesus wouldn’t sound American.

Romans wouldn’t speak English.

Pain wouldn’t be symbolic.

It would be physical, exhausting, uncomfortable, the kind of discomfort studios spend millions trying to avoid.

And it cut the process down of what would normally, we kind of guesstimated would have been an 8-hour makeup down to about a 2-hour makeup.

And that refusal created a bizarre situation.

One of the biggest stars in the world couldn’t get a movie made, not because it was small, but because it was too honest.

So Mel did something almost unheard of.

He wrote the check himself.

Roughly $30 million to shoot it.

Another $15 million to market it.

No studio shield.

No shared blame.

If it failed, it failed on him alone.

Some insiders later admitted the fear wasn’t just financial.

It was cultural.

The film didn’t fit modern storytelling rules.

It didn’t reassure the audience.

It didn’t explain itself.

It demanded endurance.

That made executives uneasy.

And here’s where the theories start creeping in.

Some believe Hollywood wasn’t afraid of the violence at all, but of the reaction.

That a film this raw, this unapologetic, might provoke something they couldn’t control, not outrage, reflection.

Others say it challenged the industry’s unspoken rule.

Never let faith feel dangerous.

Because the passion wasn’t inspirational in the traditional sense.

It was confrontational.

It asked a question without saying it out loud.

What if this actually happened like this? And once that question was asked, Mel couldn’t take it back even when every door closed, which raises the next mystery? Why was he so determined to make it even when it cost him everything? The risk that turned into a reckoning.

When Mel Gibson bet his own money on the passion of the Christ, it wasn’t just a financial gamble.

It felt personal, almost reckless.

And the people around him noticed something unsettling.

He wasn’t acting like a producer chasing profit.

He was acting like someone who believed backing out wasn’t an option.

At the time, Mel openly admitted he wasn’t in a good place.

Fame hadn’t fixed him.

Awards hadn’t calmed him.

He spoke later about addiction, inner chaos, and a growing sense that something in his life was off balance.

I mean, we’re all like um shouted out and we’ve kind of learned on the others and he’s just getting the benefit of all the mistakes we made and they all love it.

And then this story took hold not loudly, quietly, the kind of idea that doesn’t let go.

He didn’t frame the film as entertainment.

He framed it as obedience.

That’s where things get interesting because once production began, the set itself started gaining a reputation not for chaos, for heaviness.

Crew members described a strange emotional weight.

Seasoned professionals, people who’d worked war films, horror films, said this felt different, hard to explain, harder to ignore.

Then came the incidents everyone still talks about.

Jim Cavzel, playing Jesus, was struck by lightning during filming.

Not near him, on him.

He survived, but later required major heart surgeries.

I It was probably more like 3 seconds.

It felt like five, but was probably less than that.

And then and then boom.

The assistant director was also struck twice on the same production.

Statistically possible, sure, but unsettling enough that people still whisper about it.

Cavzel suffered hypothermia, a dislocated shoulder, a deep whip wound when a practical effect went wrong.

Some of the screams in the final cut weren’t acting.

They were real.

and Mel, he’d step away from the camera during the most violent scenes, not to direct, to pray.

Here’s the fun fact most people miss.

The film wasn’t marketed traditionally at all.

No flashy premieres, no late night circuits.

Instead, Gibson screened it privately for church leaders, pastors, religious groups.

Word spread underground.

By the time Hollywood realized what was happening, it was too late.

Opening day shattered expectations.

Week after week, audiences kept coming.

The film didn’t just succeed, it rewrote the rules.

But success came with a price.

Accusations, backlash, cultural firestorms, and eventually Mel’s own public collapsed just a few years later.

The secrets that followed the cast home.

Even after the cameras stopped rolling, the Passion of the Christ didn’t let go of the people who made it.

And that’s where things get really strange.

Because for a film that broke every box office rule, the cast and crew didn’t exactly ride a wave of fame.

In fact, many of them disappeared.

Let’s start with Jim Cavzel, the man who played Jesus.

Before The Passion, he was on a steady rise.

Serious dramas, major supporting roles, respect from Hollywood.

But after this film, something shifted.

Rolls dried up, projects stalled, and whispers started swirling.

Was he blacklisted? Cavzle himself later admitted that offers vanished overnight.

Big studios, big directors gone.

Some people claimed it was because he was too religious.

Others said it had nothing to do with faith, but everything to do with fear.

Fear that his face, forever linked to Christ’s torment, was too much for audiences to separate, or maybe for the industry itself to deal with.

But it wasn’t just Caviazel.

Other actors who appeared in the film stepped into a bizarre silence.

Crew members declined interviews.

Background actors turned down behindthe-scenes specials.

And when journalists tried to dig deeper, they hit a wall.

People would simply say, “I don’t want to talk about it.

” No drama, no scandal, just silence.

One of the strangest cases was Luca Leonello, the Italian actor who played Judas.

Before the movie, he was a self-described atheist, but after filming, he converted to Christianity.

According to some reports, he described the role as emotionally overwhelming, something that cracked something open inside him.

That wasn’t an isolated story.

Several people on set, extras, assistants, even makeup artists began attending Bible studies or requested baptisms while production was still ongoing.

One story that floated through the press had a background actor collapsed during a crucifixion scene, not from heat exhaustion, but from what he called spiritual pressure.

And the weirdest part, these weren’t people prone to drama.

Many had worked on major sets for years.

War films, horror flicks, action franchises.

Yet, this movie left them shaken in a way no explosion or stunt ever had.

The nightmares that kept following them.

The cameras stopped, the trailers packed up, the set in Mata emptied.

But for many who worked on The Passion of the Christ, something didn’t leave with them.

Because after filming wrapped, a new phenomenon began to surface.

Dreams.

Vivid, disturbing, and relentless.

Cast and crew began quietly admitting to a strange string of recurring nightmares.

These weren’t your average post-production stress dreams.

They were specific, visceral, often biblical in tone, sometimes violent, and eerily similar across different people who hadn’t spoken since leaving Italy.

One set technician told a friend that after he got home, he kept waking up at exactly 3:00 a.

m.

, the traditional hour associated with Christ’s death, heart racing, convinced someone was standing in his room.

He wasn’t religious.

He didn’t believe in spirits, but he began sleeping with the lights on.

Another source close to the costume department said they began having dreams of ancient languages, Aramaic and Latin phrases they didn’t speak or understand being whispered in their ear.

One of them later Googled the phrases and found they were actual lurggical lines used in funeral rights.

Even Jim Cavzel later admitted in a Christian radio interview that long after production ended, he would wake up sweating, feeling like he was still carrying the cross.

He said it was more than muscle memory.

It was something he felt beneath his skin.

And then came the stories of objects being taken home from the set.

Props, costume fragments, even stones from the location that seemed to carry a weight no one could explain.

One crew member claimed the rosary they had worn during the entire shoot went missing after they returned home and showed up weeks later at their front door, soaking wet on a sunny day.

The most chilling part, no one wanted to talk about it publicly.

These weren’t attention-seeking stories.

They were whispers, anecdotes traded cautiously between people who didn’t want to be seen as unhinged.

Some believed the film had become a spiritual lightning rod, pulling energy from a story too sacred and too raw to be dramatized without consequence.

Was it the intensity of the material? Was it the emotional toll of reliving ancient trauma? Or did the film tap into something deeper, something not just watched, but felt long after the credits rolled? The sequel that Hollywood fears even more.

Just when everyone thought The Passion of the Christ had said everything it could, Mel Gibson revealed he wasn’t done.

That’s right.

There’s a sequel and not just a quiet follow-up.

According to Gibson, it’s going to be the biggest film in world history.

His words, not ours.

And here’s the part no one saw coming.

The Passion of the Christ.

Resurrection has been in secret development for years.

Quietly, obsessively, off the radar.

Why? Because Gibson believes this one isn’t just a film, it’s a spiritual experience.

Insiders claim the sequel doesn’t simply pick up after the crucifixion.

It dives head first into the three days between death and resurrection.

A part of scripture rarely dramatized in full.

Think about that.

The descent into hell, the cosmic battle between light and darkness, the moment all of creation held its breath.

And once again, Gibson isn’t holding back.

He’s reportedly studying ancient texts, extra biblical writings, and even apocryphal sources to explore what actually could have happened in that realm beyond the physical.

In short, he wants to film what no one’s dared to put on screen.

And guess who’s returning? Jim Cavezle.

Even after all the pain, the backlash, the career fallout, he’s back.

And he said the sequel will make the original look like a walk in the park.

That’s not an exaggeration, that’s a warning.

Caviasel has dropped cryptic hints about spiritual warfare, about strange delays, about forces trying to stop this film from ever reaching theaters.

In interviews, he’s called the script powerful and controversial.

And Mel, he said he’s approaching the project with fear and trembling.

One major twist, the sequel reportedly blends realtime resurrection scenes with visions, flashbacks, and spiritual encounters unlike anything audiences have seen before.

And if the first film already shook people’s faith to the core, this one might ignite it or challenge it even more.

But here’s the wild part.

Hollywood still wants no part of it.

The sequel, like its predecessor, has struggled to find studio backing.

Too risky, too controversial, too sacred.

So Gibson’s doing it again.

Independent financing, private production, and total control.

And that leads to the most haunting question of all.

If the first film brought lightning, blood, and silence, what’s going to happen this time? The viewers who left changed and never talked about it.

Long after the debates faded and the box office numbers settled, something quieter began happening.

Something far less public.

People who watched The Passion of the Christ didn’t just remember it, they carried it.

Theaters reported things they weren’t trained to handle.

Viewers sitting in their cars long after the credits.

Strangers crying together in parking lots.

Some refusing to speak at all.

Ushers said people walked out shaken, pale, unable to explain what they’d just experienced.

This wasn’t shock from gore alone.

Plenty of violent films came before it.

This felt different.

Churches noticed it, too.

Priests and pastors across multiple countries quietly confirmed a surge in late night confessions.

Questions about faith and requests for baptism in the weeks following screenings.

Some said people showed up who hadn’t set foot in a church in decades.

Others said they came angry, skeptical, then left unsettled.

Here’s the strange part.

Many viewers said the film didn’t convince them of anything.

It didn’t preach.

It didn’t explain.

It just sat there in their mind replaying itself.

The sounds, the silence, the suffering that refused to be symbolic.

Psychologists later speculated that the film triggered something closer to collective trauma response, a reaction usually seen after real world disasters, not movies.

Others disagreed, suggesting it tapped into deeply buried cultural memory.

A story so familiar it had gone numb, suddenly made raw again.

And then there were the stories no one wanted to go on record with.

People claiming the film resurfaced longforgotten guilt, old regrets, broken relationships they suddenly felt compelled to confront.

Not miracles, not visions, just an overwhelming sense that something had been stirred.

the prop that vanished and the question it left behind.

Among the hundreds of strange stories that swirled around the passion of the Christ, there’s one that’s barely spoken about, but it lingers, not because of its size, but because of its silence.

During one of the final days of filming in Mata, a handmade nail prop used in the crucifixion scenes reportedly vanished.

Now props disappear all the time on sets, lost in transport, mislabeled, picked up as souvenirs.

But this one, it was never found.

Not during cleanup.

Not in post production inventory.

Not even after an internal sweep of all the trucks and holding areas.

Here’s where it gets weird.

The nail had been crafted to exact ancient Roman specifications.

Iron, bluntended, slightly rusted, weathered for authenticity.

It wasn’t a plastic replica.

It was real and it had weight.

One crew member said it wasn’t something you could accidentally misplace.

But after that day’s shoot, gone.

Some whispered that it was stolen, maybe by someone hoping to sell it or keep it as a twisted trophy, but no one came forward, and it never showed up online or at auctions.

Others on set believed something else entirely.

One assistant recalled that the prop had been placed beside the base of the cross for close-up shots.

After a windy break in filming, the crew returned, and the nail was missing.

No wind could have carried it off a rocky hill, and no one saw anyone touch it.

It became an unspoken rumor.

the nail that disappeared.

But here’s the part no one talks about.

In the days that followed, the mood on set shifted, even more than before.

Several crew members became ill.

One actor fainted mid-cene without warning.

The assistant director reportedly suffered a severe migraine that lasted for days.

People began snapping at each other.

Tempers rose.

And Mel, he seemed quieter, more focused.

Some say more burdened.

The letters Mel never talks about.

After the theaters emptied and the noise faded, something unexpected began arriving at Mel Gibson’s home.

Not fan mail, not hate mail, letters, hundreds of them, handwritten, messy, emotional, and according to people close to him, many were never answered.

Not because he didn’t care, but because he didn’t know how.

Some came from prisoners, men serving life sentences who said the film broke through walls nothing else ever touched.

Others came from doctors and nurses who had watched the film alone after late shifts, unable to shake the realism of the suffering.

A few were from Holocaust survivors who said they were terrified to watch it, but felt compelled to finish it anyway.

The reactions weren’t uniform.

Some were grateful, some were angry, some were shaken in ways they struggled to explain.

One recurring theme appeared again and again.

People didn’t say the film changed their beliefs.

They said it forced them to confront something they’d been avoiding.

Guilt, forgiveness, pain, responsibility.

Things modern movies rarely ask audiences to sit with.

Here’s the part that rarely gets mentioned.

According to sources close to Gibson, a small number of letters came from clergy who urged him not to make another film like it.

Not because it was wrong, but because it was too powerful.

One reportedly warned that stories like this when told without filters tend to extract a cost from the storyteller.

And then there was the Vatican.

Contrary to popular belief, the Passion of the Christ was never officially endorsed by the Vatican.

Early rumors suggested Pope John Paul II had called it as it was, but the Vatican later walked that back.

No official praise, no condemnation either, just distance, silence.

For a film that shook churches worldwide, that silence was deafening.

Mel has never publicly read those letters aloud.

He’s only hinted at them.

Said they were heavy.

Said some stories stayed with him longer than the criticism ever did.

The sound that was never meant to be there.

In a film packed with emotional intensity, physical suffering, and deep spiritual undertones, The Passion of the Christ had one moment that even the post-p production team couldn’t fully explain.

And to this day, most viewers miss it entirely.

But audio engineers didn’t.

During one of the final crucifixion scenes, when the camera lingers on Christ’s body and the wind stills, a sound was picked up in the raw recording that no one had planned.

Not Foley, not ambient track, something else, something layered beneath the rest.

It wasn’t discovered until months later during the film’s final sound mixing process.

An engineer flagged it, assuming it was a technical glitch or stray background noise.

But when they isolated the track, things got weird.

It didn’t match any known onset sound.

It wasn’t wind.

It wasn’t crew chatter, and it wasn’t in any take before or after.

It was a low, rumbling moan, human, but not entirely, almost coral, almost mournful.

The team reportedly tried to scrub it out, but each time they removed it, the emotional impact of the scene collapsed.

Something about that hidden sound, intentional or not, held a gravity that no artificial replacement could mimic.

So, Mel made a call.

Leave it in.

Here’s where the theories start.

Some people working on the sound team said it resembled Gregorian chant, slowed to near unrecognizable levels.

Others suggested it could have been a crew member reacting emotionally and caught on a hot mic.

But no one owned up to making it and it didn’t appear on any other scene recordings despite similar conditions.

One engineer later admitted off the record that it felt like the sound of grief itself.

Not from the actors, not from the audience, but from somewhere in between.

Mel has never addressed this sound directly in interviews, but insiders say he grew unusually quiet when it was brought up during editing, as if he already knew what it was.

Hit subscribe and click the card on screen

News

Burke Ramsey Speaks Out: New Insights Into the JonBenét Ramsey Case td

Burke Ramsey Speaks Out: New Insights Into the JonBenét Ramsey Case After more than two decades of silence, Burke Ramsey,…

R. Kelly Released from Jail td

R&B legend R.Kelly has found himself back in the spotlight for all the wrong reasons, as he was recently booked…

The Impact of Victim Shaming: Drea Kelly’s Call for Change td

The Impact of Victim Shaming: Drea Kelly’s Call for Change In recent years, the conversation surrounding sexual abuse and domestic…

Clifton Powell Reveals Woman Lied & Tried To Set Him Up On Movie Set, Saying He Came On To Her td

The Complexities of Truth: Clifton Powell’s Experience on Set In the world of film and television, the intersection of personal…

3 MINUTES AGO: The Tragedy Of Keith Urban Is Beyond Heartbreaking td

The Heartbreaking Journey of Keith Urban: Triumphs and Tribulations Keith Urban, the Australian country music superstar, is often celebrated for…

R. Kelly’s Ex-Wife and Daughter Speak Out About the Allegations Against Him td

The Complex Legacy of R. Kelly: Insights from His Ex-Wife and Daughter R. Kelly, the renowned R&B singer, has long…

End of content

No more pages to load