For centuries, the physical world of Jesus ministry has been filtered through scripture, tradition, and belief rather than stone, soil, and inscription.

Archaeology has often confirmed locations, patterns of daily life, and historical context, yet rarely has it suggested the existence of words attributed directly to Jesus that fall outside the canonical record.

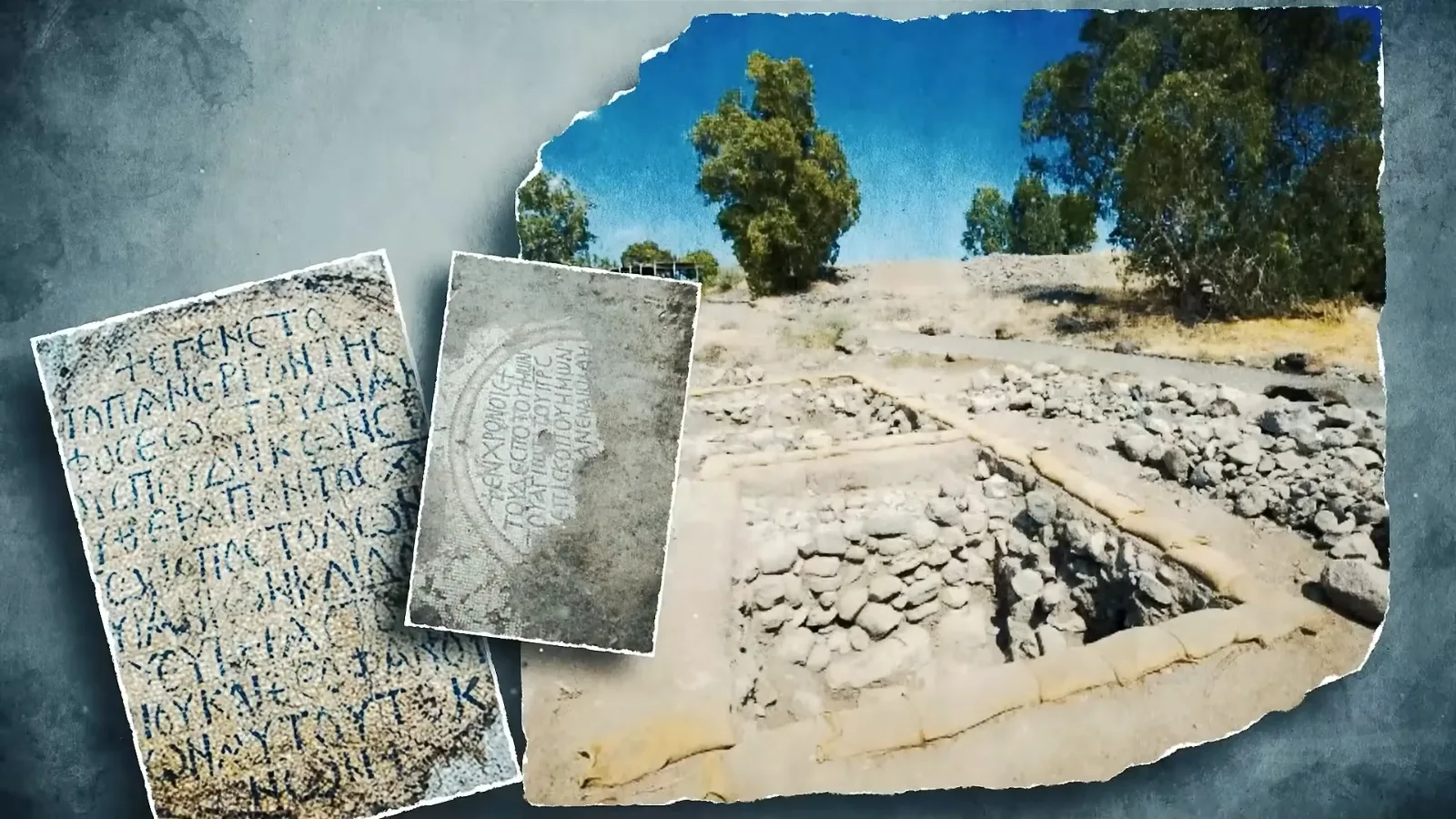

A recent discovery at the ancient site identified as Bethsaida has reignited global interest, not because it answers long standing questions, but because it introduces a warning embedded in architecture and memory rather than text.

The excavation began as many biblical archaeology projects do, with modest expectations.

The site known as El Araj lies near the northern shore of the Sea of Galilee, an area long contested by scholars as the possible location of ancient Bethsaida.

For decades, academic debate divided researchers between two competing locations, with careers and reputations invested in each position.

Bethsaida mattered not simply as a town, but as a central node in early Christianity.

According to the New Testament, it was the hometown of Peter, Andrew, and Philip, and the setting for multiple foundational events in Jesus public ministry.

In the Gospel narratives, Bethsaida appears repeatedly as a place where extraordinary acts became routine.

A blind man received sight after Jesus applied mud to his eyes using soil from the area.

Thousands were fed with minimal provisions.

Disciples departed from its shoreline during moments that would later define Christian theology.

Despite this, Bethsaida also occupies a troubling position in scripture.

It is one of only three cities openly condemned by Jesus for witnessing signs yet refusing belief.

The text records a declaration that Bethsaida would face judgment and descent, a statement that later readers interpreted symbolically.

History, however, may have rendered it literal.

By the fourth century, Bethsaida disappeared from maps.

Roman records fell silent.

Travelers reported marshland where a town was expected.

Flooding, sediment, and shifting water levels from the Sea of Galilee gradually erased visible traces of habitation.

For nearly two thousand years, its exact location remained uncertain.

In 2016, Professor R Steven Notley and archaeologist Dr Morai Avam initiated systematic excavations at El Araj.

The site was waterlogged, unstable, and difficult to work.

Groundwater flooded trenches daily, forcing the team to operate pumps continuously.

Each layer removed revealed little more than pottery shards and mud, reinforcing skepticism among critics who believed the site incorrect.

That changed during the 2019 excavation season.

At a depth of approximately 1.88 meters, a volunteer struck stone rather than sediment.

The sound drew immediate attention.

Within minutes, senior archaeologists were on their knees clearing debris by hand.

What emerged was not rubble but intentional construction.

Thick walls built from dressed stone appeared, followed by the unmistakable curve of an apse, the semicircular architectural feature typical of early Christian churches.

Carbon analysis dated the structure to the Byzantine period, between the fifth and sixth centuries.

The building covered approximately 180 square meters, an unusually large footprint for a rural church constructed on unstable terrain.

Its very presence raised questions.

Such an investment required certainty, resources, and purpose.

Excavation beneath the church floor revealed something older still.

Roman era domestic structures from the first century emerged, including fishermens houses, net weights, hooks, and coins minted during the period traditionally associated with Jesus lifetime.

These findings established continuous occupation and aligned precisely with the New Testament timeline.

Most striking was the deliberate positioning of the Byzantine church.

It was not centered on the largest or most accessible structure beneath it.

Instead, it was aligned with remarkable precision over one particular house.

Protective walls preserved that dwelling rather than destroying it, an unusual decision in ancient construction.

Scholars quickly reached consensus that the builders believed this to be the home of Peter.

In the ancient world, churches were not built casually over private residences.

The cost, labor, and engineering challenges at El Araj would have been immense.

The decision to preserve the footprint of a single house beneath a basilica indicated more than commemoration.

It suggested guardianship.

As conservators cleared the mosaic floor, Greek letters began to emerge.

The outer inscription followed familiar dedicatory patterns, referencing ecclesiastical figures and offering praise.

Within it, however, appeared language of heightened theological weight.

Peter was identified not simply as an apostle, but as chief and commander of the heavenly apostles, a phrase implying authority and hierarchy beyond standard honorifics.

Further analysis revealed that the inscription was structured as a medallion, approximately 45 centimeters in diameter.

Inside its border, barely visible due to shallow carving and centuries of wear, lay a second ring of text.

These inner letters were intentionally subtle, invisible to anyone not actively searching for them.

Advanced imaging techniques, including infrared scanning, revealed 43 additional Greek characters arranged as direct speech.

Linguistic reconstruction suggested words attributed to Jesus himself.

The translation read Guard my house for I go to prepare the heavens.

The wording immediately drew scholarly attention.

While similar language appears in the Gospel of John, the phrasing differed in critical ways.

Canonical texts refer to preparing a place.

This inscription referred to preparing the heavens, suggesting a broader cosmic scope.

More significantly, no gospel records Jesus instructing Peter to guard his house.

Early Christian scholarship recognizes the existence of agrapha, sayings attributed to Jesus that survive outside the biblical canon.

More than two hundred such sayings are known from manuscripts and patristic writings.

However, finding one embedded permanently in a mosaic floor at a major pilgrimage site elevates its significance.

Supporters of the interpretation argue that the community responsible for the church traced its lineage directly to the apostles.

They would have preserved oral traditions passed through generations, including teachings never written down.

The decision to carve the words into stone rather than parchment suggests permanence and urgency.

Skeptics urge caution.

Some scholars note that Byzantine inscriptions often expanded upon tradition to reinforce theological positions.

They argue that the phrase could reflect doctrinal development rather than historical memory.

Yet this explanation struggles to address the intentional concealment of the inner text.

If the message served public instruction, why hide it beneath centuries of foot traffic.

The question of what the house represents remains unresolved.

One interpretation holds that it refers to the physical home of Peter, the site where Jesus stayed and taught, a place considered sacred and therefore requiring protection.

Another view suggests metaphor.

The house could represent the community, the tradition, or the unwritten teachings entrusted to Peter after Jesus departure.

A more unsettling interpretation has emerged quietly among some scholars.

Bethsaida, according to scripture, was cursed.

History records its disappearance.

Yet someone remained long enough to preserve the memory of one precise location, safeguarding it through abandonment, persecution, and collapse.

When Christianity gained imperial protection, that memory surfaced in stone, accompanied by a warning rather than celebration.

The mosaic lay buried 1.

8 meters below ground, preserved by the same floods that erased the city.

Its message remained unread for fourteen centuries.

Only forty percent of the church floor has been excavated to date.

Areas near the altar, traditionally reserved for the most significant inscriptions, remain untouched.

Dr Avam has confirmed that future excavation seasons may reveal additional text, possibly extending the command beyond the phrase currently known.

Whether the instruction Guard my house is complete or merely introductory remains unknown.

What is clear is that the ancient community considered the message important enough to preserve in silence rather than proclamation.

The mosaic does not announce triumph.

It does not invite devotion.

It issues responsibility.

If those who lived where Peter lived, who inherited his memory directly, believed something required guarding across centuries, the implication reaches beyond archaeology.

It raises questions about what was remembered, what was withheld, and why.

The discovery at Bethsaida does not rewrite scripture.

It does not invalidate tradition.

Instead, it introduces tension between what was written and what was remembered.

It reminds the modern world that early Christianity was not formed solely by texts, but by places, practices, and decisions shaped under pressure.

As excavation continues, scholars emphasize restraint.

Archaeology reveals context, not certainty.

Yet context itself can be disruptive.

A hidden message, preserved beneath a church built on a vanished city, challenges assumptions about what history chose to record.

The mosaic remains silent, but its presence speaks.

It suggests that some truths were not meant for immediate disclosure, but for guardianship.

Whether humanity was meant to uncover them now remains an open question.

News

Excavators Just Opened a Sealed Chamber Under Temple Mount — And One Detail Still Terrifies Experts

For centuries, the Temple Mount in Jerusalem has stood as one of the most sensitive and symbolically powerful locations on…

50 Cent’s New Documentary Part 2 Reveals What Was Hidden About Diddy & Jay Z

The long and complicated rivalry between two of the most powerful figures in modern hip hop has resurfaced with renewed…

Former ‘Jane Doe’ speaks out and reclaims her identity after R. Kelly abuse

The unresolved case surrounding the passing of Tupac Shakur continues to resurface in public discourse nearly three decades later, driven…

A ‘Jane Doe’ in the R Kelly trials is ready to share her real name. And her story

A ‘Jane Doe’ in the R Kelly Trials is Ready to Share Her Real Name and Her Story In the…

THOUSANDS of MS 13 Gang Members Arrested in Largest Multi City FBI & ICE Crackdown

A sweeping federal enforcement operation carried out across the United States has resulted in more than one thousand arrests linked…

50 Cent Breaks Silence on Tupac — Netflix Doc Ignites SHOCKING Diddy Allegations

The renewed public conversation surrounding Tupac Shakur has returned not as nostalgia, but as inquiry. Nearly three decades after his…

End of content

No more pages to load