Archaeologists excavating land on the outskirts of Scarborough made a discovery so unexpected that seasoned professionals paused comparisons altogether.

What initially appeared to be a routine investigation ahead of development quickly transformed into one of the most significant Roman archaeological finds in Britain in several decades.

The structure uncovered does not fit established categories such as villa, temple, fort, or bathhouse.

Instead, it represents a previously unknown architectural form, one that scholars now believe may be unique across the entire former Roman Empire.

The discovery unfolded suddenly rather than gradually.

Construction work was underway on land intended for housing when excavation equipment struck carefully laid stonework.

Further investigation revealed a curved wall and an opening shaped like a doorway.

Within moments, construction halted and archaeological protocols took over.

What had been an ordinary building site became a tightly controlled excavation zone.

From the earliest exposure, it was evident that the stonework was deliberate, symmetrical, and finely executed.

This was not accidental masonry nor a fragment of a known rural structure.

As archaeologists expanded the dig, the scale and complexity of the site became increasingly clear.

Grid systems were established and soil was removed layer by layer.

The emerging plan revealed a building layout unlike anything previously recorded in Roman Britain.

At the heart of the complex lay a perfectly circular central room, a design choice almost unheard of in elite Roman architecture in the province.

From this central space, a series of rooms radiated outward with geometric precision, forming a wheel like arrangement that suggested careful planning and intentional movement control.

Roman villas in Britain typically followed rectilinear designs with wings, courtyards, corridors, and clear separations between domestic and ceremonial areas.

Temples adhered to standardized layouts reflecting religious conventions.

Military structures prioritized practicality, visibility, and defensibility.

The Scarborough complex followed none of these patterns.

Instead, it combined elite construction techniques with a spatial philosophy that emphasized symmetry, focus, and exclusivity.

Further excavation uncovered evidence of advanced engineering.

Beneath the floors lay hypocaust systems used for underfloor heating, indicating a high degree of comfort and expense.

Attached bathing facilities were discovered, constructed with craftsmanship comparable to urban bathhouses rather than rural equivalents.

The quality of materials and workmanship pointed to expert builders and significant financial backing.

This was a statement structure, built to impress a select audience rather than serve the general population.

Despite these indicators of wealth and sophistication, the building resisted classification.

Historic assessments concluded that no comparable structure existed in Britain or elsewhere in the Roman world.

The conclusion was not that the builders lacked understanding of Roman architectural norms, but that they intentionally departed from them.

The design demonstrated deep knowledge of Roman engineering principles combined with a conscious decision to break convention.

The circular core of the building suggested controlled access and restricted use.

Unlike public bathhouses or civic buildings, the layout directed visitors inward toward a shared center.

All occupants would have been positioned at equal distance from that focal point, a departure from hierarchical spatial arrangements common in Roman elite architecture.

This design choice implied a specific function centered on exclusivity, ritualized gathering, or controlled interaction among a limited group.

Once the structural outline was fully recorded, archaeologists turned to soil analysis to understand how the site had been used and abandoned.

In most Roman domestic or elite sites, long term occupation leaves behind a chaotic mixture of debris, broken ceramics, discarded tools, coins, repairs, and signs of fire or collapse.

At Scarborough, that expected pattern was absent.

Instead, the soil layers revealed an unusual orderliness.

While evidence of use was present, including pottery fragments, tiles, coins, and building materials, these items appeared in a restrained and deliberate pattern.

There were no signs of sudden destruction, no burn layers, no collapsed masonry indicative of disaster.

The evidence suggested that the building was not destroyed or abandoned in haste, but carefully dismantled.

Valuable components appear to have been removed methodically.

Structural elements were taken away while floor plans remained intact.

The site was cleaned, stripped of reusable materials, and then left behind.

This pattern pointed to a planned closure rather than decline or crisis.

Such behavior implied authority, resources, and intent.

This raised further questions about why such a building existed in this location at all.

Scarborough was not a marginal settlement in Roman Britain.

The Yorkshire region formed a critical part of the Roman military, administrative, and economic network.

At its center stood Eboracum, modern York, a major imperial hub where emperors resided and died.

From this center extended roads, forts, and coastal installations designed to secure the northern frontier.

Scarborough itself was home to a significant Roman signal station on the headland now occupied by Scarborough Castle.

This installation formed part of a chain of coastal defenses monitoring maritime traffic and potential threats.

Nearby inland forts such as Cawthorne and Lease Rigg illustrate Rome’s strategic control of the region.

Yet the newly discovered Scarborough complex shared none of the characteristics of these defensive sites.

The location of the complex further complicated interpretation.

It was not positioned on high ground for defense, nor near fertile land typical of elite villas.

It lay between established nodes of power, close enough to matter but distant enough to remain distinct.

This placement defied both military and economic logic as traditionally understood in Roman planning.

The discovery forced archaeologists to reconsider assumptions about Roman activity along the Yorkshire coast.

The complex suggested the presence of a function not previously recognized in the regional landscape.

Whether administrative, ceremonial, social, or political, its purpose lay outside conventional categories.

As excavation progressed, public attention grew rapidly.

Media coverage described the site as one of the most important Roman discoveries in Britain.

Expectations rose that the site would be preserved and opened to visitors.

Instead, archaeologists, heritage authorities, local councils, and developers reached an unexpected decision.

The entire site would be carefully reburied.

This choice initially confused and disappointed many observers.

However, it was driven by long term preservation concerns.

Exposed masonry is vulnerable to weather, frost, moisture, vandalism, and foot traffic.

Maintaining such a site would require constant intervention and significant funding.

In contrast, controlled reburial protects fragile remains by returning them to stable underground conditions.

The decision was not unique.

Internationally, similar approaches have been taken at sites such as Chaco Canyon in the United States and Laetoli in Tanzania.

In cases where exposure poses greater risk than benefit, burial is recognized as a legitimate conservation strategy.

The goal is not to erase history, but to safeguard it until better preservation methods or technologies become available.

At Scarborough, reburial involved documenting every aspect of the site in detail through scans, drawings, photographs, and reports before covering it with protective layers and landscaped open space.

The physical structure is no longer visible, but its data remains accessible to researchers.

This outcome highlighted a broader tension in modern archaeology between public access and preservation.

Allowing people to walk through ancient ruins offers powerful educational value, but it also accelerates decay.

Protecting a site often requires limiting access, even when the discovery is extraordinary.

The Scarborough complex now exists as a silent presence beneath the surface, much as it did after its deliberate abandonment nearly two thousand years ago.

Its rediscovery and reburial mirror its ancient history of careful construction and controlled closure.

The find has reshaped understanding of Roman Britain and raised new questions about how power, identity, and space were expressed at the edge of the empire.

It suggests that Roman activity in Yorkshire was more diverse and complex than previously believed.

It also underscores the importance of anomalies in archaeology, where breaking patterns reveals hidden dimensions of the past.

As technology advances, future methods may allow deeper study without disturbing buried remains.

For now, Scarborough stands as both a landmark discovery and a case study in preservation ethics.

It reminds scholars and the public alike that not all history is meant to remain visible, and that safeguarding the past sometimes requires allowing it to return to silence beneath the ground

News

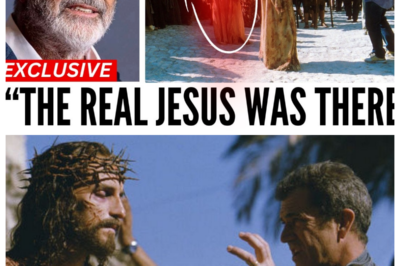

Before He Dies, Mel Gibson Finally Admits the Truth about The Passion of the Christ

**Mel Gibson Reveals the Disturbing Truth Behind The Passion of the Christ** Mel Gibson has come forward to share a…

Joe Rogan CRIES After Mel Gibson EXPOSED What Everyone Missed In The Passion Of Christ!

Mel Gibson’s Revelation on The Passion of the Christ: A Moment of Truth In a recent episode of The Joe…

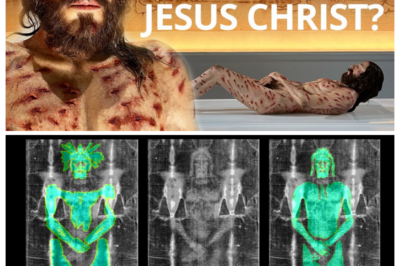

Is this the image of Jesus Christ? The Shroud of Turin brought to life

The Shroud of Turin: Unveiling the Mystery at the Cathedral of Salamanca For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has captivated…

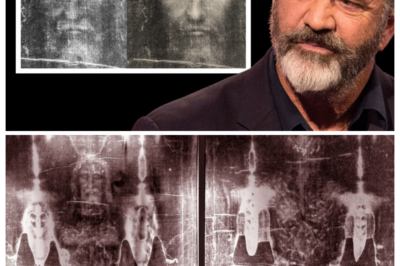

Mel Gibson: “They’re Lying To You About The Shroud of Turin!”

Mel Gibson and the Shroud of Turin: Unveiling New Insights The Shroud of Turin has long been a subject of…

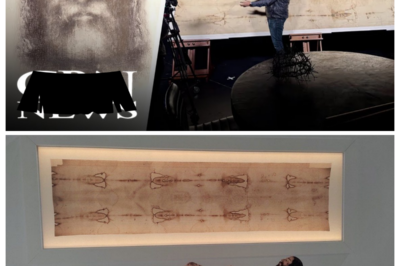

Secret Vault Under the Vatican Opened After 5000 Years & It Holds Terrifying Discovery

Unveiling the Secrets of the Vatican Archives The Vatican Archives have long been shrouded in mystery, holding some of the…

Shroud of Turin Expert: ‘Evidence is Beyond All Doubt’

Perhaps no religious artifact on planet Earth creates as much fascination and controversy as the shroud of Turin. Is this…

End of content

No more pages to load