The Apollo 11 mission remains one of humanity’s greatest achievements, a defining moment when human beings first set foot on the Moon.

Most people remember Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin as the two astronauts who descended to the lunar surface in July 1969.

Armstrong delivered the famous line about a small step and a giant leap, while Aldrin followed closely behind, exploring the powdery terrain and conducting experiments.

Yet a third astronaut played an equally vital role in the mission’s success.

His name was Michael Collins, and although he never walked on the Moon, his experience in lunar orbit became one of the most profound chapters in space exploration history.

In 2025, renewed interest in Apollo 11 has brought attention back to Collins and the extraordinary perspective he gained while orbiting alone above the lunar surface.

Far from being a forgotten figure, he has come to symbolize the quiet strength and psychological resilience required for deep space travel.

His reflections reveal not eerie secrets in the sensational sense, but something far more powerful: the emotional and philosophical impact of being completely isolated on the far side of the Moon.

The Apollo program began in 1961 with a bold objective: to land a man on the Moon and return him safely to Earth before the end of the decade.

The initiative demanded enormous financial investment, technological innovation, and human courage.

Before Apollo 11, several precursor missions tested spacecraft systems, docking maneuvers, lunar orbit procedures, and extravehicular activities.

Each stage brought scientists closer to the historic landing.

On July 16, 1969, Apollo 11 launched from Kennedy Space Center.

The three man crew consisted of Commander Neil Armstrong, Lunar Module Pilot Buzz Aldrin, and Command Module Pilot Michael Collins.

After entering lunar orbit on July 19, Armstrong and Aldrin transferred into the Lunar Module Eagle, leaving Collins aboard the Command Module Columbia.

On July 20, Eagle descended to the Moon’s surface while Collins remained in orbit.

At 2:56 a.m.GMT on July 21, Armstrong stepped onto the lunar surface, followed by Aldrin.

The two astronauts spent approximately two and a half hours outside the module, collecting rock samples, deploying scientific instruments, and planting a flag.

Meanwhile, Collins circled above them, responsible for maintaining Columbia’s systems and preparing for the critical rendezvous that would reunite the crew.

Michael Collins was born in 1930 in Rome, where his father served as a United States Army officer.

Raised in a military family, he moved frequently during childhood and developed an early fascination with aviation.

After graduating from the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1952, he joined the Air Force and became a fighter pilot.

He later attended test pilot school at Edwards Air Force Base, where he flew advanced aircraft and gained technical expertise that would prove essential in spaceflight.

Selected by NASA in 1963, Collins first flew in space during the Gemini 10 mission in 1966.

There, he performed two spacewalks and conducted complex docking maneuvers.

Though originally assigned to Apollo 8, a medical procedure forced him to step aside temporarily.

He was later reassigned to Apollo 11, placing him at the center of history.

As Command Module Pilot, Collins carried enormous responsibility.

Columbia served as the mothership, the only vehicle capable of returning the astronauts to Earth.

If anything went wrong during docking, Armstrong and Aldrin could have been stranded.

Collins had to calculate orbital mechanics with precision, execute engine burns accurately, and maintain life support systems in perfect condition.

During each orbit around the Moon, Collins experienced a unique phenomenon.

For approximately 48 minutes of every two hour circuit, Columbia passed behind the Moon’s far side.

During that time, radio communication with Earth and with the Lunar Module was completely blocked.

The Moon itself acted as a physical barrier to radio waves, creating total silence.

Some observers later described Collins as the loneliest man in history.

Yet he rejected that characterization.

In his autobiography Carrying the Fire, he explained that he felt not loneliness but profound solitude.

The silence was serene rather than frightening.

With no communication from Earth and no visual contact with his crewmates, he was truly alone, perhaps more isolated than any human before him.

The far side of the Moon presented a stark landscape of rugged craters and mountainous terrain.

Unlike the near side, which faces Earth and appears relatively smooth in places, the far side is heavily cratered and visually dramatic.

As Collins orbited, he witnessed Earth rising above the lunar horizon, a small blue sphere suspended in darkness.

That image would become central to his reflections.

Scientists later described this transformative perspective as the overview effect.

Astronauts who observe Earth from space often report a deep emotional shift, recognizing the planet’s fragility and unity.

For Collins, seeing Earth from lunar orbit reinforced the interconnectedness of humanity.

National borders disappeared.

Conflicts seemed insignificant against the vast cosmic backdrop.

The medical and psychological components of such a mission were critical.

Space agencies understood that extended isolation could strain mental health.

Collins had to remain focused, calm, and technically sharp while experiencing complete radio silence.

His training emphasized discipline and mental resilience.

He managed checklists, monitored fuel levels, and prepared for docking procedures even during periods of communication blackout.

The rendezvous between Columbia and Eagle was among the most complex operations of the mission.

After Armstrong and Aldrin launched from the lunar surface, Collins executed precise maneuvers to align the spacecraft.

A miscalculation of even a small degree could have jeopardized the mission.

Instead, the docking was successful, and the crew reunited in orbit before beginning their journey home.

The return to Earth required another critical maneuver known as trans Earth injection.

Collins ignited the spacecraft engine to break free from lunar orbit and set the trajectory toward Earth.

Again, precision was essential.

The entire mission depended on these calculations.

In later interviews, Collins spoke about how the quiet moments behind the Moon allowed him to contemplate existential questions.

He considered humanity’s place in the universe and the delicate balance that sustains life on Earth.

Though not previously inclined toward overt spirituality, he described sensing an ordered cosmos rather than chaotic randomness.

The far side’s radio silence has also attracted scientific interest.

Because it is shielded from Earth’s radio interference, it offers ideal conditions for radio astronomy.

In 2019, a robotic mission successfully landed on the far side, using relay satellites to maintain communication.

These technological advances underscore how unique Collins’ experience was in 1969, when he orbited without any direct contact during blackout periods.

Far from revealing supernatural mysteries, Collins’ reflections highlight the profound psychological impact of space travel.

He demonstrated that isolation, when combined with purpose and preparation, can foster clarity rather than fear.

His calm demeanor ensured mission success and protected his crewmates’ safe return.

Apollo 11 concluded with a splashdown in the Pacific Ocean on July 24, 1969.

The crew were welcomed as heroes.

Armstrong and Aldrin became global icons, yet Collins remained characteristically modest.

He understood that exploration is a collective endeavor requiring visible pioneers and steadfast guardians alike.

In 2025, discussions about long duration missions to Mars have renewed attention to Collins’ experience.

Future astronauts may face even longer periods of communication delay and solitude.

His example provides valuable insight into the psychological preparation required for deep space travel.

Michael Collins passed away in 2021, but his legacy endures.

He embodied the collaborative spirit that defined Apollo 11.

Though he never stepped onto the lunar surface, he witnessed something equally extraordinary: Earth suspended in the infinite darkness, a fragile home shared by billions.

His story reminds humanity that exploration is not only about physical distance but also about perspective.

From the far side of the Moon, he saw the planet without borders, glowing quietly against the void.

In that silence, he found not fear, but understanding.

The achievement of Apollo 11 was not solely the first step on another world.

It was also the moment when one astronaut, orbiting alone, discovered a deeper appreciation for the world he left behind.

News

Bruce Lee’s Daughter in 2026: The Last Guardian of a Legend 10t

As a child, Shannon Lee would sometimes respond to playground bravado with quiet certainty. When other children joked that their…

Selena Quintanilla Died 30 Years Ago, Now Her Husband Breaks The Silence Leaving The World Shocked 10t

Thirty years have passed since the world lost one of Latin music’s brightest stars, yet the name Selena Quintanilla continues…

Scientists New Plan To Retrieve the Titanic Changes Everything! 10t

More than a century after the RMS Titanic slipped beneath the icy waters of the North Atlantic, the legendary ocean…

Drunk Dancer Challenged Michael Jackson — His Response Stunned 80,000 Fans

July 16th, 1989, Wembley Stadium. 80,000 people watched as a drunk backup dancer stumbled onto the stage during Billy Jean…

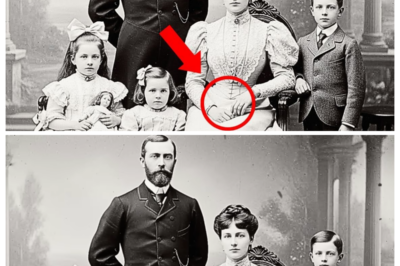

1890 Family Portrait Discovered — And Historians Recoil When They Enlarge the Mother’s Hand

This 1890 family portrait is discovered, and historians are startled when they enlarge the image of the mother’s hand. The…

What D1ana’s Secret DNA Test Really Revealed – The Palace Sh0cked! 6p

Pr1ncess D1ana 0rdered a secret DNA test f0r Harry 1n 1995, n0t because she d0ubted he was Charles’s s0n, but…

End of content

No more pages to load