The story of the Antikythera Mechanism begins with a storm that changed the course of history.

In October 1900, the Aegean Sea was in chaos, hammering a small crew of sponge divers from the island of Symi.

They had set out for sponge fishing, not archaeology, but the violent winds drove them off their course and forced them to seek desperate refuge along the cliffs of a remote island called Antikythera.

Their captain, Dimitrios Kontos, decided they should dive while waiting for the weather to settle.

It was a practical choice made for survival, yet it opened the door to one of the greatest mysteries of ancient civilization.

Diver Elias Stadiatis plunged forty five meters beneath the waves expecting the usual sponge beds.

Instead, he returned to the surface gasping in terror.

He claimed the seafloor was littered with the bodies of men and horses.

Convinced he had misunderstood the scene, the captain descended himself.

What he saw was astonishing but far from a graveyard.

He found the shattered remains of a large Roman shipwreck scattered across the seabed, surrounded by marble and bronze statues that had crumbled into eerie humanlike shapes.

To prove what he had discovered, he hauled up the corroded arm of a bronze warrior.

The divers had accidentally located what would become the most important shipwreck of the ancient world.

The Greek government responded quickly and sent naval assistance.

What followed was the first major underwater archaeological operation in history.

It was a brutal task.

The divers wore heavy canvas suits, copper helmets, and lead shoes, working without modern dive computers or any real understanding of decompression sickness.

They could stay at the seabed for only minutes at a time.

Each descent was a gamble with their lives.

Two divers were permanently paralyzed, and one diver, Georgios Kritikos, died during the operation.

Still, they persisted and dragged up a wealth of ancient treasures, including marble sculptures, bronze figures, ceramics, and jewelry.

Amid the grandeur, a small, unremarkable lump of calcified bronze and wood was pulled from the sea.

It was green, cracked, and coated in centuries of mineral deposits.

It did not resemble treasure and was tossed aside into a storage crate.

When the artifacts were transported to the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, the statues captured everyone’s attention.

The corroded lump was ignored and left to dry in a storeroom, slowly cracking under the change in temperature and humidity.

Unknown to everyone, the most advanced technological artifact of the ancient world was inside that lump, waiting to be rediscovered.

As the object dried, the exterior corrosion shrank and fragmented.

It eventually broke open, revealing something completely unexpected.

Archaeologist Valerios Stais examined the pieces and noticed a bronze gear embedded inside.

It was a precision component with evenly spaced teeth.

The appearance of such a gear in a first century shipwreck was not simply unusual; it was impossible based on what historians believed about ancient engineering.

The accepted narrative was that sophisticated gear systems were a medieval invention, first appearing in Europe around the fourteenth century.

Yet here was a gear that predated them by more than a thousand years.

The discovery hinted at a lost chapter of human innovation.

For decades, the device remained an enigma.

The surface was too corroded to reveal details, and researchers lacked the technology to examine the interior.

Early attempts to understand it began in the nineteen seventies when historian of science Derek de Solla Price and physicist Charalambos Karakalos scanned the fragments using gamma rays.

The images showed outlines of more gears hidden deep within the rocklike crust.

Price identified more than thirty gears and concluded that the object was an ancient astronomical calculator.

His findings were groundbreaking, but the images were blurry and incomplete.

In the following decades, researchers applied increasingly advanced scanning technologies.

Michael Wright and Allan George Bromley used linear tomography to view the fragments in cross section.

This allowed Wright to build one of the first functional reconstructions of the device.

He discovered a special pin and slot mechanism that enabled the gears to mimic the irregular speed of the moon’s orbit.

This was an engineering achievement that seemed far beyond the capabilities of the ancient world.

The real breakthrough came in the early two thousands.

A collaboration known as the Antikythera Mechanism Research Project brought in a twelve ton microfocus X ray computed tomography machine built specifically for the study of this artifact.

The scans revealed an entire world hidden within the corroded mass.

The interior structure included more than thirty bronze gears packed so tightly that they resembled the movement of a high precision watch.

The researchers discovered a differential gear inside the device.

This type of gear was believed to have been invented in the Renaissance, yet the ancient Greeks had used it to calculate the subtle motion of the moon.

The scans also revealed the full layout of the mechanism.

The front face displayed the sun and moon moving through the zodiac, indicating their positions in the sky.

The back of the device contained two large spiral dials.

The upper spiral tracked the Saros cycle, which predicts solar and lunar eclipses over an eighteen year period.

The lower spiral tracked the Metonic cycle, a nineteen year calendar that aligns lunar and solar time.

Smaller dials tracked additional astronomical cycles, including the seventy six year Callippic cycle and a four year cycle marking the ancient Olympic Games.

The machine was, in essence, a portable model of the cosmos.

Though the scans revealed its structure, one part remained a mystery.

The front calendar ring, containing a circle of tiny holes used to track the days of the year, had been mostly destroyed in the wreck.

Only a few fragments with incomplete rows of holes survived.

For more than a century, researchers assumed the ring had 365 holes corresponding to the Egyptian solar calendar.

This was considered the most logical explanation because the Egyptian system was widely used by astronomers for its simplicity and lack of leap years.

But in 2024, a new analysis overturned this assumption.

Physicists Graham Woan and Joseph Bayley from the University of Glasgow used Bayesian statistical methods similar to those used to detect gravitational waves.

They treated the surviving fragments as a partial signal and used probability analysis to determine the original number of holes.

Their findings were precise and mathematically undeniable.

The ring contained exactly 354 holes, not 365.

This matched the length of a lunar year, which includes twelve lunar cycles.

The implications were enormous.

A 354 day lunar calendar pointed directly to regions in Greece that relied heavily on lunar timekeeping.

This strongly suggested a Corinthian origin, and the most prominent Corinthian colony known for scientific innovation was Syracuse, the home of Archimedes.

Ancient writings by Cicero mentioned a machine built by Archimedes capable of modeling the movements of celestial bodies.

Many scholars believed this was a myth.

Yet the lunar calendar discovery aligned perfectly with the traditions of Archimedes and his mechanical school.

The Antikythera device was likely created by his intellectual descendants.

The inscriptions on the machine revealed something even more profound.

The recovered text, glimpsed through high resolution CT scans, formed a dense instruction manual carved directly into the metal plates.

The text explained how to operate the device, how to read its dials, and how to interpret its astronomical predictions.

But it also went deeper into the realm of ancient belief.

The Greeks viewed eclipses as signs of divine displeasure.

They believed these celestial events foretold disasters such as war, plague, or the fall of kings.

The Antikythera Mechanism did not merely calculate astronomical phenomena.

It predicted omens.

The eclipse dial included not only the timing of eclipses but descriptions of their appearance.

The inscriptions classified eclipses as black, red, or fiery.

These colors were connected to astrological interpretations, signaling fate and warning of danger.

In this sense, the mechanism served as both an astronomical calculator and a tool for political and spiritual authority.

Anyone who possessed it could foresee events that others believed were controlled by the gods.

Despite its sophistication, the mechanism nearly disappeared from history.

The ship carrying it was likely transporting Greek treasures seized by the Romans.

If the vessel had reached its destination, the mechanism would have been admired for a time but eventually dismantled for its valuable bronze.

This was the fate of almost all ancient machines.

Bronze was precious, and devices without an expert to maintain them quickly became useless.

Once broken, they were melted down for tools, weapons, or currency.

The Antikythera Mechanism survived only because disaster intervened.

The shipwreck preserved it in a deep, oxygen poor environment that prevented total decay.

When modern researchers finally recovered it, the device stood alone as the last surviving example of a technological tradition that vanished from the world.

It represents a lost era when ancient engineers reached a level of mechanical sophistication that would not be matched again for more than a thousand years.

The mechanism forces us to confront the fragility of progress.

It reminds us that knowledge can be lost, that brilliance can disappear, and that civilizations can forget technologies that once seemed permanent.

If the ancient Greeks were capable of building an analog computer capable of predicting eclipses and modeling celestial cycles, the path of human innovation might have unfolded differently.

Had this knowledge survived, the Industrial Revolution could have begun centuries earlier.

Humanity might have reached the modern age far sooner than it did.

Today, the Antikythera Mechanism sits in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

It is a silent monument to the heights ancient science once reached and a warning about how easily those heights can crumble.

Its gears, dials, and inscriptions tell a story not only of brilliance but of loss, reminding us that technological progress is never guaranteed.

It must be protected, preserved, and passed on, or it risks disappearing beneath the waves like the forgotten machine that once mapped the heavens.

News

Muslims Stormed a Church to Burn the Eucharist Then THIS HAPPENED…

I led seven men into a Catholic church to burn what Christians called the body of Christ, convinced we were…

Muslims Stormed a Church to Steal the Communion Unaware What Jesus Had Planned…

Four Muslim men walked into a church to prove Christianity was fake by taking communion and feeling nothing. What happened…

Arab Royal Mocked Jesus Publicly in Dubai, Then Dropped to One Knee in Shock vd

On December 15th, 2018, I stood before 5,000 Muslims in Dubai and spent 45 minutes mocking Jesus Christ, calling him…

A Catholic Mass Was Interrupted When Muslim Men Stole Chalice—What Happened Next Shocked Everyone

On December 8th, 2019, I walked into a Catholic church with three other Muslim men and grabbed the sacred cup…

R Kelly Thrown In “The Hole” After Alleged Prison Assassination 😳 New Trial Filing GOES LEFT

Our Kelly’s legal team just dropped bombshell allegations claiming the singer is not just serving time. He’s literally fighting for…

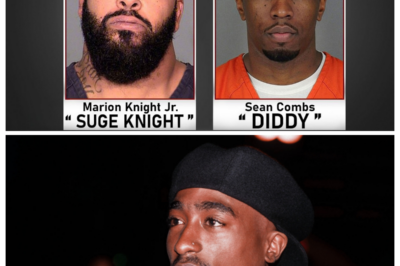

Diddy & Suge Knight CHARGED For Tupac’s Death

Nearly three decades after the death of Tupac Shakur, renewed debates continue to surface regarding who was ultimately responsible and…

End of content

No more pages to load