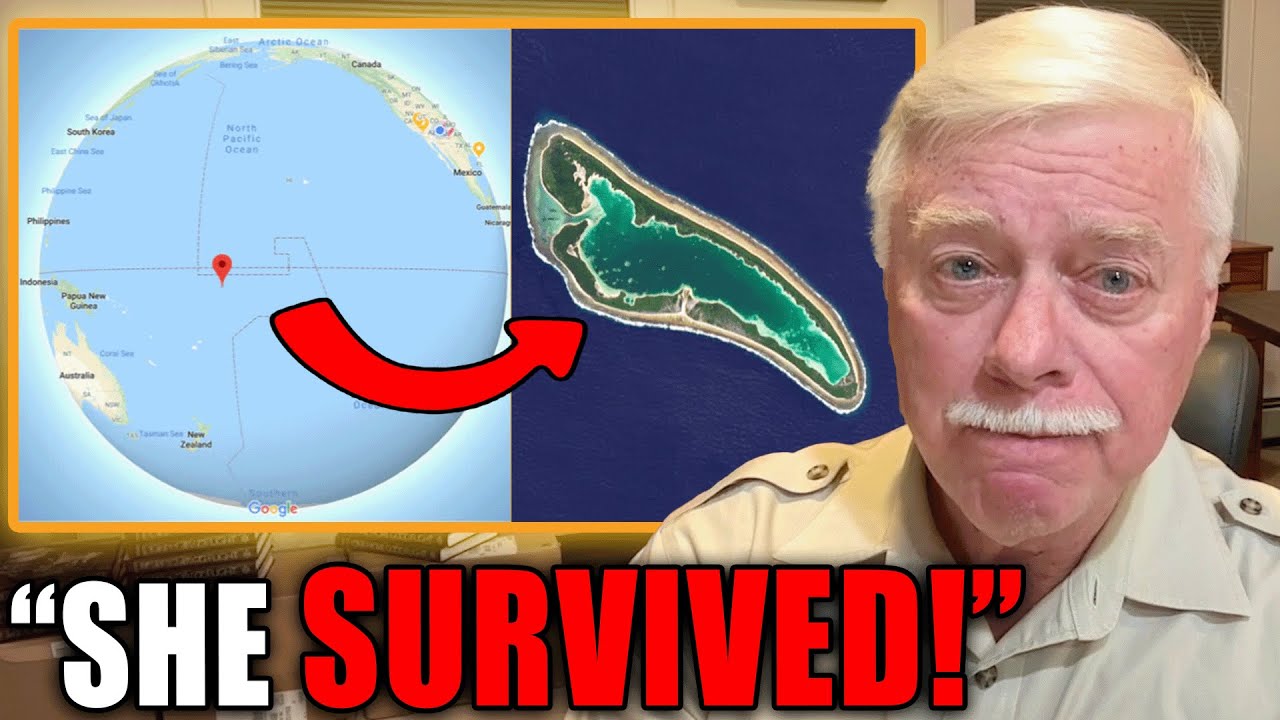

Amelia Earhart disappeared in July 1937 while attempting to complete a round the world flight along the equator.

For decades the dominant explanation held that the aircraft ran out of fuel near Howland Island and fell into the Pacific Ocean.

The story appeared simple and tragic, a skilled pilot lost in a vast sea.

Yet a detailed reconstruction of events by later investigators suggests a far more complex ending, one involving celestial navigation, radio distress calls, and a remote coral island that was briefly examined and then forgotten.

In the years after the disappearance many people proposed theories, most of them speculative and unsupported.

Serious researchers were often reluctant to become involved.

The idea of finding a tiny aircraft in an enormous ocean seemed hopeless, and the subject attracted sensational claims that discouraged careful study.

For a long time professional investigators avoided the case entirely, convinced that nothing new could be learned.

That attitude began to change when two retired military aerial navigators approached an experienced researcher with a carefully reasoned proposal.

Both men had spent their careers using the same navigation methods that Fred Noonan, Earhart navigator, relied upon in long distance flights.

They did not bring rumors or legends.

They brought charts, calculations, and an analysis of Earhart final radio transmission.

Shortly before contact was lost, Earhart reported that the aircraft was running on a specific line of position and flying north and south along that line.

In celestial navigation a line of position represents all possible locations from which a particular observation could have been made.

When fuel was nearly exhausted, the standard procedure was to follow that line until land was found.

The navigators showed that if the crew had followed the reported line, they would have reached a small uninhabited island far to the southeast of Howland.

At first the idea seemed improbable.

Surely the United States Navy had already considered such an obvious possibility.

Further research confirmed that this was not a new theory at all.

It was exactly what naval planners believed during the first days after the disappearance.

Their conclusion had been based not only on navigation logic but also on a remarkable pattern of radio signals that began soon after Earhart failed to arrive.

Across the Pacific, professional radio operators, Coast Guard stations, and naval ships began to receive weak distress calls on Earhart assigned frequencies.

At the same time, civilians in North America reported hearing her voice clearly on household shortwave radios.

The reports came from different locations and different listeners, many of whom had not been searching for anything unusual.

They simply happened to be tuning across the dial when they encountered a female voice calling for help.

The strange combination of weak signals nearby and strong signals far away puzzled officials.

The explanation emerged from the physics of radio transmission.

Earhart transmitter operated primarily on two medium frequencies intended for short range communication.

Those signals faded rapidly with distance.

However, the transmitter also produced harmonic frequencies, higher multiples that could reflect from the ionosphere and travel thousands of miles before returning to Earth.

Anyone positioned where those reflected waves descended could hear the signal with startling clarity.

As reports accumulated, Pan American Airways joined the effort.

The company had established radio direction finding stations on Oahu, Midway, and Wake to guide its transpacific passenger flights.

Operators at those stations recorded bearings on the mysterious signals and plotted their intersections.

The strongest and most consistent crossings fell near a lonely atoll then known as Gardner Island, now called Nikumaroro.

Naval officers reviewed the data and reached an important conclusion.

If the signals continued night after night, the aircraft could not be floating in the sea.

Salt water would have disabled the radio within hours.

The battery that powered the transmitter would also have failed unless it was being recharged.

The only way to recharge it was to run the right engine, the one connected to the generator.

That meant the aircraft had landed intact, with its wheels down on solid ground.

With this reasoning the Navy decided that Earhart and Noonan had probably reached Gardner Island.

A battleship was dispatched from Pearl Harbor, a journey of nearly two thousand miles that required a full week.

By the time the ship arrived the radio signals had ceased.

On the morning of July ninth, three floatplanes launched from the battleship and flew low over the island.

The pilots saw no aircraft.

Thick vegetation covered much of the land, and the narrow beaches sloped steeply into the lagoon.

There was no obvious place to land and no wreckage visible from the air.

The crews did notice signs that suggested recent human activity, but they assumed these were left by native coconut workers who were known to visit many islands in the region.

This assumption proved to be crucial.

In reality Gardner Island had not been inhabited or harvested since the nineteenth century.

There should have been no recent footprints, fires, or shelters.

The pilots did not know this.

Concluding that the island held nothing of interest, they reported negative results.

The Navy then abandoned the island hypothesis and redirected the search toward open ocean, looking for debris or oil slicks.

Nothing was found.

Within weeks the official verdict hardened into certainty.

Earhart and Noonan were said to have run out of fuel and crashed at sea.

The explanation required no further investigation and no uncomfortable questions.

The dramatic radio reports were dismissed as hoaxes or misinterpretations.

The possibility of a survivable landing on an uninhabited island faded from memory.

Decades later, renewed examination of the original records revealed how fragile that conclusion had been.

The navigation logic was sound.

The radio evidence was extensive and documented by reliable observers.

Even the brief aerial survey contained clues that were misunderstood.

Modern researchers began to assemble these elements into a coherent narrative.

According to this reconstruction, Earhart reached the vicinity of Howland but failed to see the island.

Following standard procedure, she turned onto the reported line of position and flew southeast until land appeared.

Gardner Island lay directly on that line.

The aircraft likely landed on the wide reef flat at low tide, sustaining little damage.

For several days Earhart used the radio to call for help, running the engine periodically to recharge the battery.

As tides rose and fell, seawater would have reached the aircraft, gradually disabling the equipment.

After the last transmissions the plane may have been swept into deep water or broken apart by surf.

Earhart and Noonan, stranded without rescue, would have attempted to survive on the island with limited supplies.

Archaeological expeditions to Nikumaroro in recent years have uncovered objects that support this scenario.

Pieces of aluminum consistent with aircraft construction, remnants of improvised camps, and human bones reported by colonial officials in the nineteen forties all point to the presence of a castaway during the relevant period.

Although definitive proof remains elusive, the pattern of evidence aligns closely with the early naval assessment that was set aside in nineteen thirty seven.

The story illustrates how complex events can be simplified into comforting myths.

The image of a sudden crash in an empty ocean relieved institutions of responsibility and ended a costly search.

It also obscured the courage and endurance that may have marked Earhart final days.

Reconsidering the case does not diminish her achievement.

Instead it restores her as an active navigator who followed her training and made a deliberate decision under extreme pressure.

It also highlights the skill of early radio operators and navigators whose careful observations were nearly forgotten.

The mystery of Amelia Earhart remains unsolved in a strict legal sense, yet the island hypothesis offers a coherent explanation that accounts for navigation data, radio science, and historical records.

It suggests that the world came remarkably close to finding her and then turned away.

In the end the disappearance stands not only as an aviation legend but as a lesson in how evidence can be overlooked when assumptions harden too quickly.

Somewhere on a remote Pacific reef, the final chapter of a pioneering flight may still be written in coral and rust, waiting for the moment when attention finally returns to the place where the first searchers almost found the truth.

News

The Shocking Decree: A Tale of Faith and Revelation

The Shocking Decree: A Tale of Faith and Revelation In a world where tradition reigned supreme, a storm was brewing…

Chinese Z-10 CHALLENGED a US Navy Seahawk — Then THIS Happened..

.

At midafternoon over the South China Sea, a routine patrol flight became an unexpected lesson in modern air and naval…

US Navy SEALs STRIKE $42 Million Cartel Boat — Then THIS Happened… Behind classified mission briefings, encrypted naval logs, and a nighttime surface action few civilians were ever meant to see, a dramatic encounter at sea has ignited intense speculation in defense circles. A suspected smuggling vessel carrying millions in contraband was intercepted by an elite strike team, triggering a chain of events survivors say changed the mission forever.

What unexpected twist unfolded after the initial assault — and why are military officials tightening the blackout on details? Click the article link in the comment to uncover the obscure behind-the-scenes developments mainstream media isn’t reporting.

United States maritime forces have launched one of the most ambitious drug interdiction campaigns in modern history as a surge…

$473,000,000 Cartel Armada AMBUSHED — US Navy UNLEASHES ZERO MERCY at Sea Behind silent maritime sensors, black-ops task force directives, and classified carrier orders, a breathtaking naval ambush is rumored to have unfolded on international waters. Battleships, drones, and SEAL teams allegedly struck a massive cartel armada hauling nearly half a billion dollars in contraband, sending shockwaves through military circles.

How did the U.

S.

Navy find the fleet before it vanished — and what happened in those final seconds that no cameras captured? Click the article link in the comment to uncover the obscure details mainstream media refuses to reveal.

United States maritime forces have launched one of the most ambitious drug interdiction campaigns in modern history as a surge…

T0p 10 Las Vegas Cas1n0s Cl0s1ng D0wn Th1s Year — Th1s Is Gett1ng Ugly

Las Vegas 1s c0nfr0nt1ng 0ne 0f the m0st turbulent per10ds 1n 1ts m0dern h1st0ry as t0ur1sm sl0ws, 0perat1ng c0sts surge,…

Governor of California Loses Control After Larry Page ABANDONS State — Billionaires FLEEING!

California is facing renewed debate over wealth, taxation, and the mobility of capital after a wave of high profile business…

End of content

No more pages to load