The Second World War left a profound mark on Europe, not only through its battles and political upheaval but also through the vast and often hidden infrastructure created by the warring nations.

Among the most remarkable remnants of that era are the bunkers constructed by Nazi Germany, Japan, and other powers.

These structures were built for a variety of purposes, ranging from military command posts to weapons factories and even chemical production facilities.

Decades later, the rediscovery of these bunkers continues to astonish historians, archaeologists, and the public, revealing the scale and ambition of wartime engineering and the human cost associated with their construction.

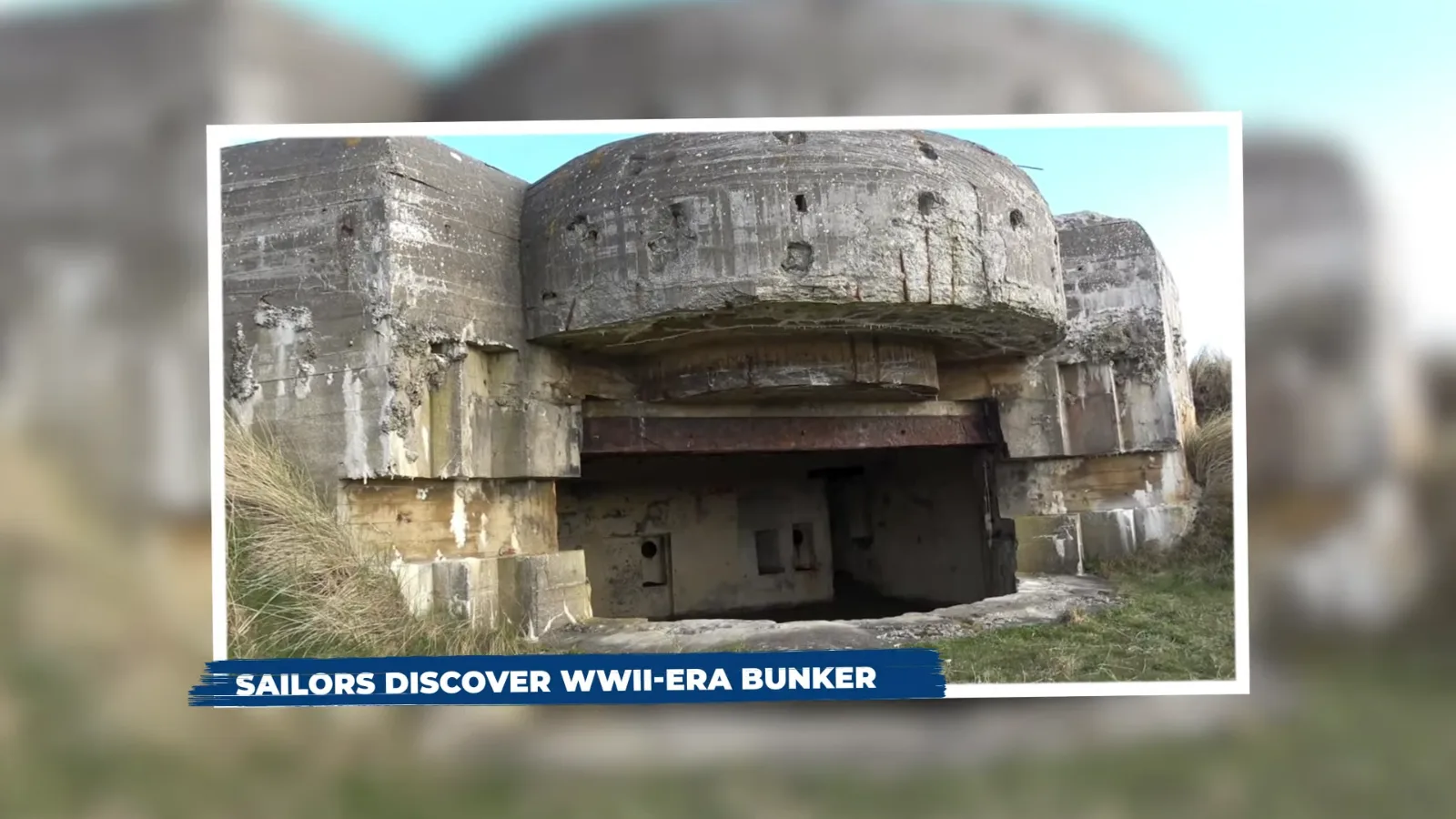

Recently, sailors exploring a dense forest along the old defenses of the Atlantic Wall stumbled upon a long-forgotten bunker from the Second World War.

The massive structure, partially buried under earth and debris, immediately drew comparisons to ancient architectural wonders due to its monumental size and robust construction.

Its thick concrete walls, possibly lined with moisture-resistant sealants, reflect the German military’s meticulous planning and concern for durability.

Inside, the sailors discovered a range of artifacts that illustrated the daily reality of soldiers stationed there.

Among the items were an ammunition box with its original locks intact, coils of barbed wire, a functional air pump, and fragments of military equipment.

These relics offered a tangible connection to the past, demonstrating the extensive preparation that went into fortifying the European coastline against potential invasions.

This discovery is part of a broader pattern of uncovering hidden wartime infrastructure.

In Belgium, a dune restoration project at Villims Park revealed three long-buried bunkers built by German forces during the occupation.

Measuring six by seven meters externally and featuring reinforced concrete walls and roofs one meter thick, these structures exemplified the intensity of wartime fortifications.

Excavation teams uncovered evidence of extensive infrastructure, including brick-lined trenches, concrete tracks for transporting personnel and supplies, wells, and remnants of military equipment.

Everyday items like utensils, cables, and water pipes were also found, alongside ammunition debris.

These finds provide insight not only into the military function of the bunkers but also into the lives of the soldiers who inhabited them.

Belgium’s coastal defenses were part of the massive Atlantic Wall, a network of fortifications constructed by the German army between 1942 and 1944 to prevent Allied invasions.

In the Villims Park area, the defensive complex, known as Stutz Heist, included around sixty military structures, ranging from bunkers and radar posts to barracks and artillery positions.

While many fortifications were deliberately demolished after the war, others remained hidden under dunes and forests, preserving a violent chapter of history beneath a seemingly peaceful landscape.

Such discoveries serve as a time capsule, offering historians a glimpse into the scale and thoroughness of wartime preparation.

Similar rediscoveries have occurred in France.

In the Gironde region along the Atlantic coast, a 120-meter-long bunker built in 1943 remained sealed and forgotten for over seventy years.

Archaeologists reopening the site found metal-framed beds, communication equipment, electrical generators, and other gear that suggested the facility had served as a command post for a garrison responsible for coastal defense.

The bunker’s walls were nearly two meters thick, reflecting the Germans’ focus on protection and resilience.

These preserved features reveal the strategic importance of the Atlantic Wall and underscore the meticulous planning behind Germany’s wartime fortifications.

In Scotland, forestry workers uncovered another previously unknown bunker in a dense southern forest.

This structure, roughly seven meters long and three meters wide, had been part of a secret network used by a covert resistance force during the war.

Known as Churchill’s Secret Army, these auxiliary units were trained for guerrilla operations, including sabotage and ambush, and their bunkers were designed for extreme secrecy.

The discovery revealed the sparse living conditions within, including rotting bed frames and minimal personal items, illustrating the sacrifices made by soldiers prepared to act behind enemy lines.

The scale and ambition of these bunkers extended far beyond small defensive positions.

In the Sudetes Mountains of Lower Silesia, archaeologists rediscovered Project Ree, a vast underground complex carved into solid rock.

Initiated in 1943 under the Nazi regime, the project consisted of interconnected tunnels and halls, some rising ten to twelve meters high.

The complex included aboveground structures believed to serve as headquarters and officer messes, along with power stations and infrastructure to supply electricity to the subterranean city.

Historians speculate that Project Ree may have been intended as a command center for the Nazi elite, including Hitler, while other sections possibly served industrial purposes such as underground weapons production.

The tunnels were constructed under brutal conditions, often by forced labor from concentration camps, resulting in immense human suffering and high mortality rates.

France’s northern regions also hosted massive bunkers constructed for the German long-range missile program.

One such facility, Lacupole, was designed to launch V2 rockets toward England.

Built into a chalk quarry, Lacupole featured a hemispherical concrete dome approximately seventy meters wide and five meters thick, intended to protect the site from Allied bombings.

Beneath the dome lay tunnels and chambers for rocket assembly, storage, fuel production, workshops, and barracks.

Despite its size and ambition, Lacupole never launched a single rocket, as Allied bombing raids under Operation Crossbow destabilized the infrastructure and forced the Germans to abandon the project.

The site, constructed with forced labor, was later opened as a museum, preserving the chilling legacy of Nazi technological ambition.

Another French bunker, Sirakut Fif One, was built for a similar purpose, designed to store and launch V1 rockets.

The massive concrete structure measured over two hundred meters long, thirty-six meters wide, and ten meters high.

Despite heavy Allied bombing, the facility was never completed or used operationally.

Its construction, employing a radical method of placing the roof before excavating the interior, reflected the Germans’ engineering ingenuity and determination to shield their weapons from aerial attack.

The abandoned site remains a stark reminder of the destructive ambitions of wartime technology and the human cost of its construction.

Germany also produced specialized bunkers for chemical warfare.

In the northern town of Falenhagen, a four-story underground complex was constructed to manufacture chlorine trilouide and nerve agents such as sarin.

Concealed beneath ten to fifteen meters of earth, the facility spanned roughly 14,000 square meters and featured tunnels, storage areas, ventilation shafts, and safety installations.

While the bunker produced only a fraction of its intended output before capture by Soviet forces in 1945, it later served as a command and control center during the Cold War.

The transformation of a deadly chemical production facility into a military headquarters underscores the enduring strategic value of subterranean infrastructure.

One of the most notorious bunker networks was Middleba Dora, located in the Konstein Mountains of Germany.

Originally intended as underground fuel storage, the site was converted into a weapons factory and concentration camp network when surface factories became vulnerable to Allied attacks.

The tunnels housed twin rail tracks, assembly halls for missiles and bombs, and sleeping quarters for forced laborers.

Workers endured extreme conditions, with many dying from exhaustion, malnutrition, or disease.

When liberated by American forces in April 1945, authorities found a haunting scene of abandoned machinery, incomplete rockets, and mass graves, highlighting the human cost of the Nazi war machine.

The rediscovery of World War II bunkers continues to shed light on the enormous scale and complexity of wartime infrastructure.

From simple defensive posts to vast underground cities, these structures reflect not only military strategy but also the ingenuity, ambition, and brutality of the era.

Each find, whether in forests, dunes, or mountains, offers historians an opportunity to examine the daily lives of soldiers, the logistical challenges of warfare, and the ethical implications of forced labor.

Sailors, archaeologists, and forestry workers who uncover these hidden sites are confronted with relics of a world once shrouded in secrecy.

Items such as ammunition boxes, barbed wire, gas masks, communication equipment, and machinery serve as a stark reminder of the realities of war.

Beyond their material significance, these discoveries allow us to reconstruct historical narratives and better understand the interplay between military innovation, human endurance, and suffering.

In addition to their historical value, these bunkers often act as tangible time capsules.

Each artifact, wall, and tunnel tells a story about strategic planning, engineering challenges, and human resilience.

Sites such as Lacupole, Sirakut, Falenhagen, and Middleba Dora exemplify the diversity of functions these underground structures served—from rocket production and chemical warfare to secret resistance operations and garrison housing.

The scale of construction, the secrecy surrounding their operations, and the human effort required to build them underscore the extraordinary lengths nations went to in preparation for war.

The continued exploration of these bunkers also raises broader questions about what remains hidden beneath the landscapes of Europe.

Forests, dunes, and mountains still conceal countless bunkers and wartime relics, waiting to be rediscovered.

Each new find contributes to a more complete understanding of the Second World War, revealing the global scope of military planning and the technological, human, and ethical dimensions of warfare.

From small forest hideouts in Scotland to massive chemical production facilities in Germany, the rediscovered bunkers of World War II provide a striking reminder of the past.

They bear witness to the ambitions, fears, and hardships of those who built and occupied them.

For historians and the public alike, these sites serve as both cautionary tales and educational resources, offering insight into one of the most devastating conflicts in human history.

The discoveries made by sailors, archaeologists, and workers in recent years remind us that history is often hidden just beneath the surface, waiting for those who are willing to uncover it.

As these bunkers are explored, documented, and preserved, they offer an enduring connection to the events of the past.

Each concrete wall, tunnel, and artifact provides a glimpse into the daily realities of soldiers, prisoners, and forced laborers.

The rediscoveries not only illuminate the logistical and strategic ingenuity of wartime powers but also the profound human consequences of war.

Whether as sites of military ambition, instruments of terror, or memorials to suffering, these bunkers ensure that the history of World War II continues to be remembered, studied, and understood.

News

Rappers Reveal Tupac Shakur IS ALIVE IN 2026

Nearly three decades after the official death of Tupac Shakur, speculation about his fate remains one of the most persistent…

Tupac’s Killer Finally Admitted In Leaked Classified Prison Call

Authorities in Nevada are intensifying their case against Duane Keith Davis, the man charged in connection with the 1996 fatal…

30 Years Later, Suge Knight Finally Exposed The Shocking Truth About Tupac’s Death

In September 1996, the world of hip hop was shaken by the fatal shooting of Tupac Shakur on the Las…

1 Minute Ago: Nancy Guthrie Case Endend! 3 Private Footages Reveal Every Suspect’s Face!

Investigators in Pima County are confronting a critical moment in the disappearance of Nancy Guthrie, as three newly analyzed pieces…

New Witness Steps Forward About Tupac’s Murder, And It’s Terrifying

The long and painful saga surrounding the 1996 k*lling of Tupac Shakur has taken another dramatic turn. Nearly three decades…

Chris Rock & Dave Chappelle TEAM UP to EXPOSE Will Smith And It’s BAD

The moment when Will Smith walked onto the stage at the 94th Academy Awards and struck Chris Rock became one…

End of content

No more pages to load