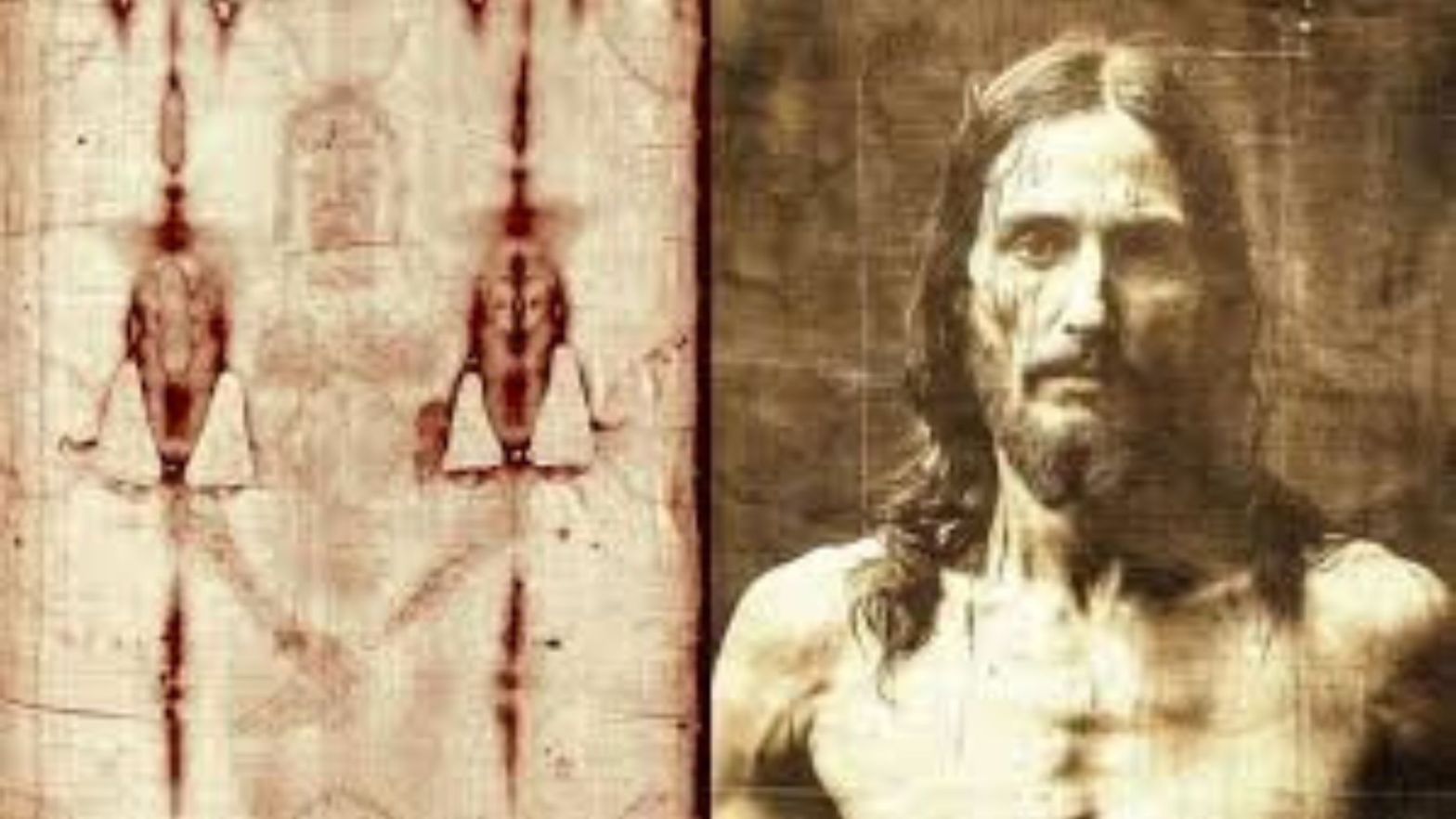

For centuries, the Shroud of Turin has occupied a unique and uneasy place at the crossroads of faith, history, and science.

Neither fully accepted nor definitively dismissed, the linen cloth bearing the faint image of a crucified man has resisted simple explanation despite relentless scrutiny.

In recent years, however, the debate surrounding the Shroud has entered an entirely new phase.

Advances in artificial intelligence, applied not to theology but to forensic imaging and spatial analysis, have produced results that challenge long-standing assumptions and deepen rather than resolve the mystery.

At first glance, the Shroud appears unremarkable.

The image is barely visible, more suggestion than depiction, a ghostlike outline that fades under direct inspection.

Yet when lighting conditions shift or digital enhancement is applied, a full-length human figure emerges, visible from both front and back, aligned as if laid out for burial.

The man appears to have suffered extensive trauma consistent with crucifixion, including wounds at the wrists and feet, a puncture in the side, and widespread scourge marks across the back and shoulders.

These features have fueled centuries of debate over whether the cloth is a medieval creation or an authentic burial shroud dating to antiquity.

What has consistently set the Shroud apart from other historical artifacts is not merely what it depicts, but how the image exists.

Microscopic examination has failed to detect paint, dye, or pigment.

The coloration does not penetrate the threads but appears confined to the outermost fibrils of the linen fibers, altering them at a depth measured in microns.

No known artistic technique, ancient or medieval, produces such an effect.

The image also behaves like a photographic negative, with light and dark values reversed, a property not understood until the advent of photography in the nineteenth century.

When the Shroud was first photographed in 1898, the negative revealed a startling clarity, exposing anatomical detail invisible to the naked eye.

These anomalies alone ensured the Shroud would remain controversial, but recent developments have intensified scrutiny.

Researchers began applying artificial intelligence tools commonly used in medical imaging, forensic reconstruction, and archaeological analysis to high-resolution digital scans of the cloth.

The goal was not to authenticate or debunk the Shroud, but to determine whether additional information could be extracted from the image using techniques designed to identify spatial relationships and depth.

What emerged surprised even cautious observers.

Rather than flattening the image or introducing distortion, the AI detected consistent depth data encoded across the entire figure.

Variations in image intensity correlated with the distance between the body and the cloth, allowing the software to reconstruct a coherent three-dimensional model.

Facial features projected naturally.

Body proportions aligned with human anatomy.

Subtle contours of muscle and bone appeared spatially accurate.

This behavior differs fundamentally from that of paintings or photographs, which lack true depth information and collapse into noise when subjected to similar analysis.

The implications were immediate and unsettling.

If the Shroud were the result of artistic creation, it would require a method capable of encoding three-dimensional spatial data into fabric without the use of pigment, tools, or visible technique.

No historical process fits that description.

The AI did not invent depth or impose structure.

It merely translated what was already present in the data.

The image, it appeared, functioned less like artwork and more like a physical record.

As the reconstructed body became clearer, medical professionals were invited to examine the results.

These specialists, trained to interpret trauma patterns rather than religious symbolism, approached the data without context or commentary.

Their conclusions were striking.

The wrist wounds aligned precisely with anatomical structures capable of supporting body weight, contradicting centuries of artistic tradition that placed nails through the palms.

The shoulders showed signs of prolonged strain consistent with suspension.

The back displayed dozens of injuries matching the distinctive marks of a Roman flagrum, a whip fitted with metal or bone fragments designed to tear flesh.

Facial swelling and nasal damage suggested blunt-force trauma delivered from multiple angles.

Perhaps most notably, the posture encoded in the image reflected the physiological struggle associated with crucifixion.

Victims die not quickly, but through exhaustion and asphyxiation, repeatedly pushing upward to breathe until they can no longer do so.

The reconstructed body showed evidence of this process frozen in time.

These findings did not rely on biblical texts but on modern forensic understanding, knowledge unavailable to medieval artists and largely misunderstood until recent centuries.

Yet even these medical insights failed to address the most persistent question: how the image formed in the first place.

Further analysis of the linen fibers reinforced earlier conclusions.

The discoloration affected only the surface fibrils, with no penetration, no residue, and no signs of chemical application.

AI-assisted pattern recognition found no repeating motifs or irregularities associated with human craftsmanship.

Instead, the image appeared to result from a single, uniform event affecting the cloth simultaneously rather than incrementally.

Some researchers cautiously suggested that the image formation resembled the effects of an intense but extremely brief energy interaction, capable of altering molecular structures without generating heat or combustion.

Others resisted such speculation, emphasizing that no definitive mechanism has been identified.

What remained clear was that every proposed explanation accounted for some features of the Shroud while failing to explain others.

The object continued to defy comprehensive understanding.

The final stage of AI analysis focused on the face.

Using only spatial data extracted from the cloth, the system reconstructed facial contours without artistic enhancement.

The result depicted a Middle Eastern man in early adulthood, with features neither idealized nor stylized.

The expression was neutral, even calm, despite clear evidence of severe trauma.

Observers noted that the stillness suggested the moment captured was not one of suffering but of rest following it.

The face did not appear designed to persuade or impress.

It appeared simply human.

Reactions to this reconstruction varied widely.

Some researchers viewed it as a technological milestone.

Others reported an unexpected emotional impact, finding that the abstraction of the Shroud had given way to a sense of personal presence.

Yet the reconstruction did not confirm identity.

It did not prove the Shroud belonged to Jesus of Nazareth.

It merely demonstrated that the image encoded information consistent with a real human body subjected to a specific form of execution.

Rather than resolving debate, artificial intelligence has complicated it.

Skeptics continue to argue that correlation does not equal causation and that technology cannot authenticate historical identity.

Supporters counter that dismissing the Shroud as a forgery now requires explaining a convergence of anomalies unprecedented in known art or fabrication.

Carbon dating results from the late twentieth century remain contested due to concerns over sampling and contamination, particularly given evidence of medieval repairs following documented fires.

What distinguishes the current moment is a shift in perspective.

The Shroud is no longer treated simply as a problem awaiting solution, but increasingly as a phenomenon demanding sustained study.

It resists reduction without resorting to irrationality.

It invites scrutiny without yielding closure.

For scientists, it exposes the limits of analytical tools.

For historians, it challenges assumptions about technological capability.

For believers and skeptics alike, it complicates narratives of certainty.

Artificial intelligence was expected to demystify the Shroud of Turin.

Instead, it has rendered the object more complex, revealing layers of structure previously invisible while leaving fundamental questions unanswered.

In doing so, it has ensured that the Shroud remains firmly situated in the present, not as a relic of superstition or a curiosity of the past, but as an unresolved intersection of data, history, and human experience.

Whether future technologies will narrow or deepen the mystery remains unknown.

What is certain is that the Shroud continues to resist disappearance, demanding not belief or disbelief, but humility before what remains unexplained.

News

Bob Lazar Warns AGAIN: New Buga Sphere X-Rays Confirm His 1989 Warning..

In March 2025, a short and unremarkable video quietly surfaced online and then vanished just as quickly. The clip, filmed…

Rob Reiner’s Wife’s Final Report Exposes 7 Chilling Details No One Expected

A newly released surveillance video has added an unsettling new dimension to the investigation surrounding the deaths of Rob Reiner…

Nick Reiner’s 5 Best Defenses in Parents’ Disturbing Murders

The double homicide case involving Nick Reiner has rapidly evolved into one of the most closely watched criminal proceedings in…

After the Murders, What Nick Reiner’s Actions Tell Us

In the aftermath of the brutal killings of Rob and Michelle Reiner, public attention has shifted from the shocking nature…

NBA Legends You Didn’t Know Had Deadly Diseases

Professional basketball is often celebrated as a showcase of peak human performance. Speed, strength, endurance, and resilience are placed on…

1 MIN AGO: Palace CONFIRMS Camilla’s Cruel Move Against Catherine — William Furious

Tensions at Buckingham Palace: The Controversial Move by Queen Camilla Recent reports have emerged from Buckingham Palace, stirring up significant…

End of content

No more pages to load