For over a century, the mummy believed to be King Thutmos II rested quietly in a museum, its origins a tantalizing enigma.

While scholars had long known the name of this pharaoh from inscriptions and temple reliefs, the location of his tomb remained a mystery—until this week, when archaeologists announced the discovery of a royal burial that had eluded the world for more than 3,000 years.

Hidden in a part of the desert considered unsuitable for a king’s resting place, the tomb of Thutmos II is the first newly identified pharaoh’s tomb in the Luxor region since Howard Carter famously uncovered Tutankhamun’s in 1922.

Thutmos II, the fourth pharaoh of Egypt’s illustrious 18th dynasty, ruled around 1490 to 1479 BCE.

Born to Thutmos I and a secondary wife, Mutnofret, he secured his place on the throne by marrying his fully royal half-sister, Hatshepsut, a union that produced at least two known children: a daughter, Neferura, and a son, Thutmos III, who would become one of Egypt’s most celebrated warrior pharaohs.

Thutmos II’s reign, however, was brief and overshadowed by the powerful figures surrounding him.

Scholars debate whether he ruled for three or thirteen years, but records suggest that most military campaigns and administrative accomplishments were orchestrated by his generals, rather than the king himself.

Architecturally, his mark on Egypt was limited: a limestone gateway at Karnak, initiated in his reign but completed under Thutmos III, and a scattering of monuments across Elephantine and Semna, none rivaling the scale of his predecessors or successors.

As a result, Thutmos II earned a reputation as a “between king”—essential for the dynastic lineage, yet easy to overlook when standing among monuments that boldly bear other rulers’ names.

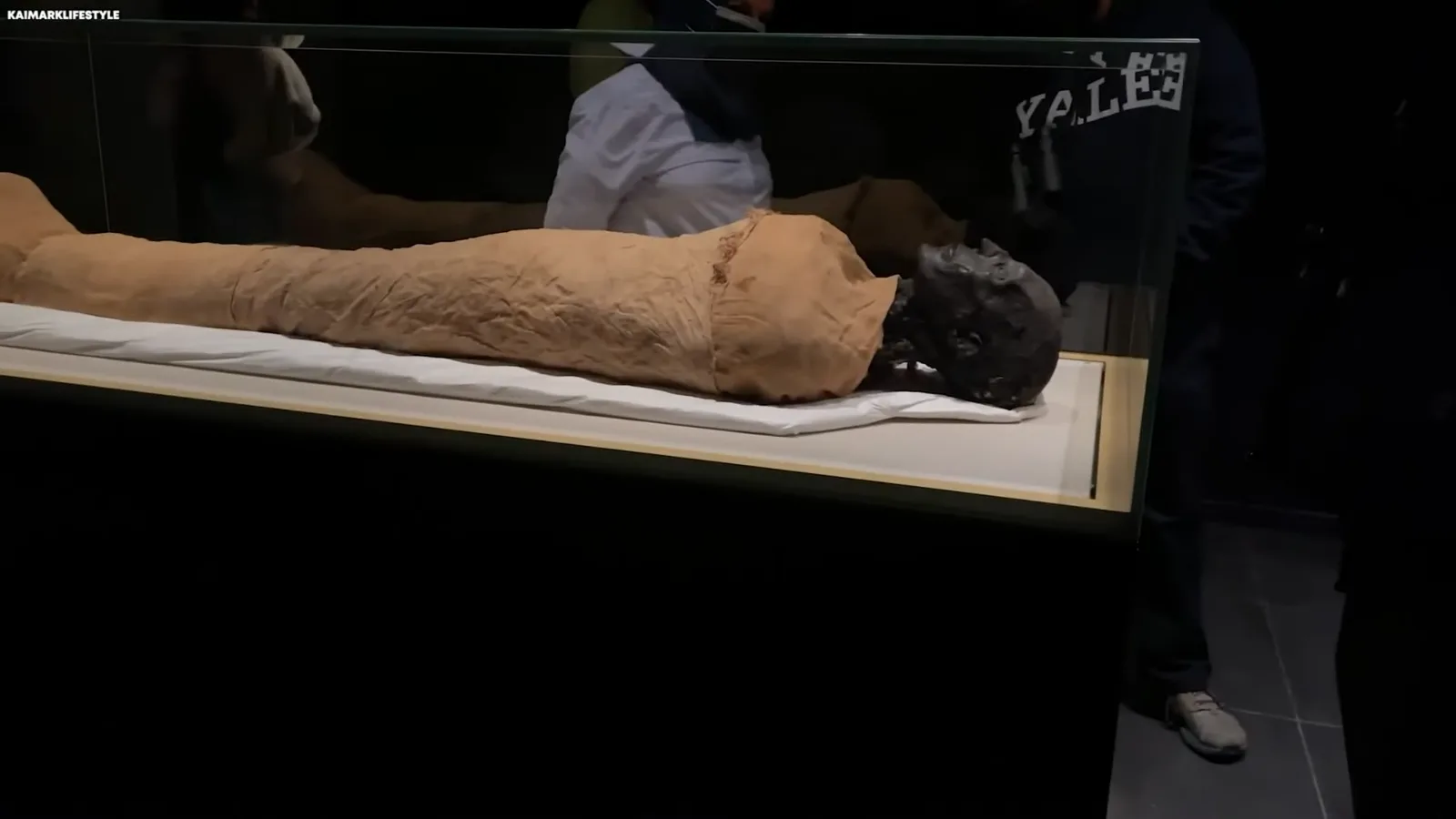

Despite this, his mummy, discovered in 1881 at the hidden royal cache of Deir el-Bahari near Luxor, became a cornerstone for Egyptian history.

The mummy was displayed in the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization in Cairo, though some modern scholars question its identification, noting that the skeletal remains suggest an age inconsistent with historical records.

For decades, the location of Thutmos II’s tomb remained a gaping question mark in the map of royal burials.

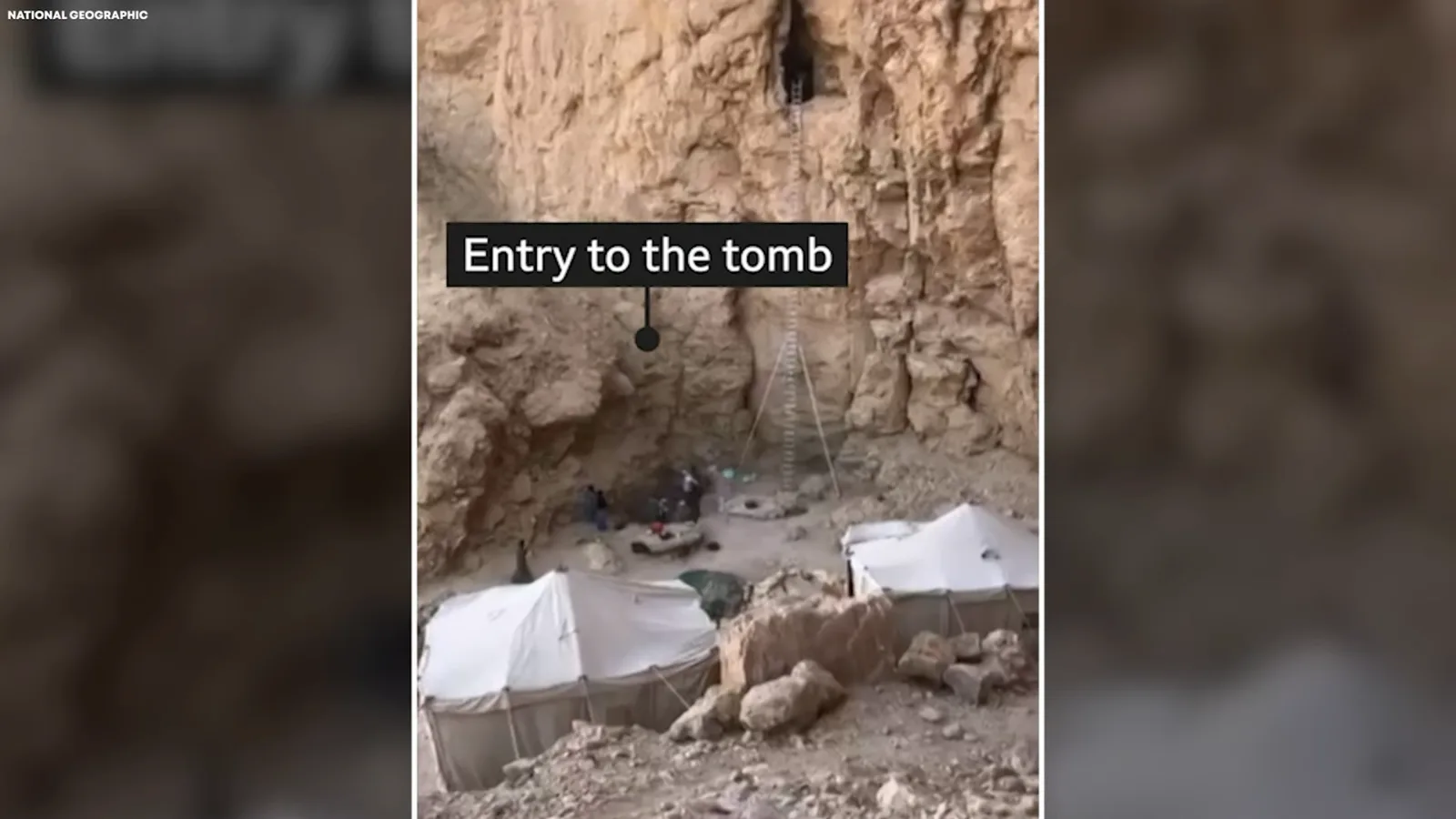

The breakthrough came from the Western Wadis, a cluster of narrow, rocky valleys located approximately two miles west of the famed Valley of the Kings.

Unlike the tourist-friendly paths of Luxor’s main tombs, the Western Wadis are remote, steep, and treacherous, largely overlooked for centuries.

Early excavations in the area had uncovered tombs of royal women, including foreign wives of Thutmos III and Neferura, daughter of Thutmos II and Hatshepsut, whose name appeared faintly on a worn carving.

These finds hinted at a concentration of royal burials in the back valleys, but much of the terrain remained unexplored.

In 2007, the New Kingdom Research Foundation (NKRF), led by archaeologist Piers Litherland and later joined by geospecialist Judith Bunbury, began systematically mapping the remote Western Wadis.

Over the next decade, they meticulously documented every slope, gully, and cliff face, collaborating closely with Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities.

Their patience was rewarded in the autumn of 2022, when in a branch known as Wadi Sea, the team discovered a deep pit containing ritual deposits, including the bones of a young calf.

In ancient Egypt, such foundation deposits—carefully placed near tombs at the time of construction—signaled the presence of something significant.

Expecting a nearby tomb for a royal woman, the team instead uncovered a stairway carved directly into the bedrock, descending deeper than anticipated.

This narrow entrance, later labeled Wadi 4 on excavation plans, led to months of painstaking work.

The upper corridor had been blocked for centuries by hardened rubble, a mix of stone and sediment nearly as solid as concrete.

Workers used small tools, soft brushes, and solar-powered lamps, carefully removing debris to prevent further damage to the fragile structure.

Only after extensive excavation did the team gain access to the first chamber—a space that immediately revealed its royal significance.

The room was in ruin.

Floors were uneven, plaster had crumbled, and walls were marred by deep scars.

Yet, above the chaos, traces of a deep blue ceiling dotted with golden stars signaled a royal burial.

The star-painted ceiling, a hallmark of kings’ tombs in the New Kingdom, indicated that this was no ordinary tomb.

Faint fragments of hieroglyphs and painted figures clung to the upper walls, hinting at a once-complete decorative program.

However, the chamber was almost entirely empty—no stone sarcophagi, no nested coffins, no gold funerary mask, and virtually no remaining grave goods.

Only scattered wood, smashed alabaster jars, and broken plaster fragments suggested the tomb’s former opulence.

This scarcity puzzled the archaeologists.

Even looted tombs typically leave at least partial traces of treasures.

The team responded by cataloging every fragment meticulously.

Conservators cleaned minute plaster pieces, photographed them in high resolution, and documented their exact locations.

Weeks of analysis revealed key inscriptions, including parts of royal titles and the name of Thutmos II’s chief wife, Hatshepsut—confirming the tomb’s identity.

For the first time, the long-lost tomb of Thutmos II had been identified, sparking celebrations among the team, complete with traditional meals and spontaneous festivities.

Understanding why the tomb had suffered such devastation required close observation.

The chamber bore clear evidence of repeated flooding.

Thin, smooth lines of mud on the walls, reaching chest height, indicated past water levels.

Roof plates had collapsed, and cracks ran across the remaining stone.

The tomb’s entrance, positioned beneath a natural rock groove, funneled stormwater directly into the corridor, turning heavy rains into destructive torrents.

The first major flood after burial deposited mud and stone, soaking coffins and furniture, and undermining the chamber’s structural integrity.

Subsequent storms compounded the damage, eventually leaving the tomb nearly inaccessible.

Ancient caretakers faced a dilemma.

Re-excavating the original entrance was too dangerous due to the unstable rubble and constant risk of further floods.

Instead, they carved a secondary passage from above, allowing them to raise coffins and large objects through a gentler, upward-sloping tunnel into the open air.

The rescued burial was relocated to a safer location, and the external landscape was reshaped to conceal the intervention.

A man-made mound, over 75 feet thick in places, was constructed from limestone chips, mud plaster, and other debris.

The mound was carefully engineered to mimic a natural hillside, likely hiding a second, secure tomb where Thutmos II’s burial could be protected from both thieves and floods.

Even in its damaged state, the tomb offered invaluable insights into Egyptian funerary practices.

The surviving ceiling fragments revealed a partial copy of the Amduat, an ancient text outlining the twelve-hour nightly journey of the sun god through the underworld.

Each hour depicted gods assisting the sun god, gatekeepers controlling access, and enemies of divine order being punished in terrifying detail.

Scenes included bound figures thrown into fiery lakes, severed bodies, and serpentine chaos monsters restrained to prevent harm to the sun boat.

This imagery was not merely decorative; it was a guide for the deceased king, promising safe passage through dangers to achieve rebirth at dawn.

Modern technology played a crucial role in reconstructing the fragmented Amduat.

Using photogrammetry, the team created detailed three-dimensional models from hundreds of overlapping photographs.

Reflectance transformation imaging allowed scholars to detect shallow brushstrokes and etched lines invisible to the naked eye.

Artificial intelligence, trained on large databases of hieroglyphs, assisted in recognizing damaged symbols, which experts then verified.

Through these methods, researchers digitally reassembled the once-complete narrative, effectively restoring a tomb that centuries of decay had rendered illegible.

The significance of Thutmos II’s tomb extends beyond its own walls.

It represents the first newly identified pharaonic burial in over a century, offering insights into the hidden complexities of royal interments during a period often overshadowed by more famous rulers.

The discovery also challenges assumptions about the burial practices of the 18th dynasty, revealing the adaptability of ancient Egyptians in safeguarding royal remains against natural disasters and potential looters.

Today, archaeologists continue to explore the man-made mound outside the tomb.

Beneath it may lie the so-called backup tomb, possibly an untouched royal burial awaiting modern discovery.

Every rock, block, and fragment is carefully examined to prevent destruction, with the hope that it could yield treasures or texts unrecorded by history.

Meanwhile, the original chamber, though ravaged, continues to teach scholars about the perilous balance between ritual, environment, and preservation in ancient Egypt.

Thutmos II’s rediscovered tomb is more than a historical site—it is a testament to human perseverance across millennia.

From the careful planning of ancient builders who engineered both the tomb and its protective mound, to the modern ingenuity of archaeologists employing AI and advanced imaging techniques, the story of this lost pharaoh underscores the enduring human fascination with legacy, mortality, and the mysteries of the past.

For the first time in generations, the “between king” has a place in the archaeological record, his journey through life and the underworld etched once more in the stars above his final resting place.

News

Black CEO Denied First Class Seat – 30 Minutes Later, He Fires the Flight Crew

You don’t belong in first class. Nicole snapped, ripping a perfectly valid boarding pass straight down the middle like it…

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 7 Minutes Later, He Fired the Entire Branch Staff

You think someone like you has a million dollars just sitting in an account here? Prove it or get out….

Black CEO Denied Service at Bank — 10 Minutes Later, She Fires the Entire Branch Team ff

You need to leave. This lounge is for real clients. Lisa Newman didn’t even blink when she said it. Her…

Black Boy Kicked Out of First Class — 15 Minutes Later, His CEO Dad Arrived, Everything Changed

Get out of that seat now. You’re making the other passengers uncomfortable. The words rang out loud and clear, echoing…

She Walks 20 miles To Work Everyday Until Her Billionaire Boss Followed Her

The Unseen Journey: A Woman’s 20-Mile Walk to Work That Changed a Billionaire’s Life In a world often defined by…

UNDERCOVER BILLIONAIRE ORDERS COFFEE sa

In the fast-paced world of business, where wealth and power often dictate the rules, stories of unexpected humility and courage…

End of content

No more pages to load