The Shroud of Turin is one of the most extraordinary and debated artifacts in human history.

For centuries, it has inspired fascination, skepticism, and religious devotion.

Believers have long held that the shroud is the burial cloth of Jesus Christ, carrying the imprinted image of his crucified body.

Skeptics, meanwhile, have insisted it is an elaborate medieval forgery.

In recent years, science has entered the debate, revealing astonishing findings that may finally redefine what this relic represents.

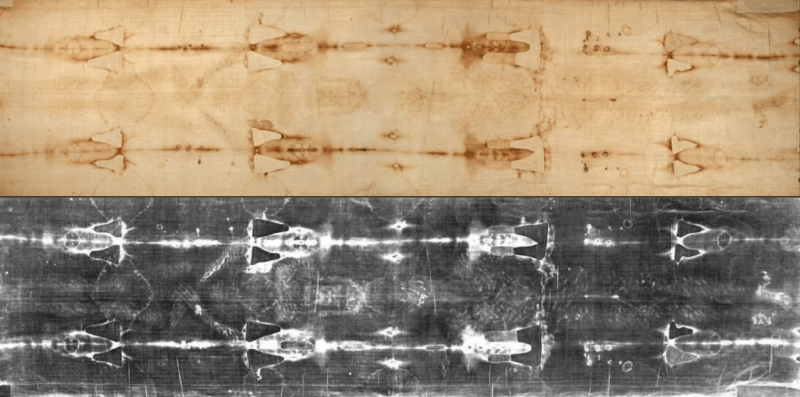

The shroud is a linen cloth, measuring approximately four meters long and one meter wide, bearing the faint but unmistakable imprint of a man.

For centuries, it has been a silent witness to a story that blends faith, history, and science.

Deep within its fibers, modern researchers have discovered DNA, pollen, and microscopic traces of human contact spanning thousands of years.

These discoveries have transformed the shroud from a religious icon into a complex historical and biological archive.

The first dramatic revelation came over a century ago, in May 1898, when amateur photographer Secondo Pia was allowed to photograph the shroud during a public exhibition in Turin.

Using the slow, technical photographic processes of the time, Pia developed his glass plate negatives late that night in his darkroom.

What emerged astonished him.

On the photographic negative, the image of the man on the shroud appeared in startling detail.

The face, previously obscured by the fabric’s shadows, was now fully visible.

Deep-set eyes, a broken nose, a forked beard, and bruising on the cheeks revealed the visage of a man who had endured extraordinary suffering.

For the first time, the world could see what Pia described as a “majestic, calm, yet agonized” expression.

This discovery challenged both religious and skeptical assumptions.

Unlike any painting or artistic representation, the image on the shroud behaves as a photographic negative.

Inverting light and dark tones produces a highly detailed positive image, a phenomenon that no medieval artisan could have anticipated or created.

Photography would not exist for another eight centuries, making it impossible for a forger in the 14th century to replicate such an effect.

The shroud’s image is not a painting, pigment, or drawing.

It is a chemical imprint, a three-dimensional representation that has confounded scientists and artists alike.

Over the decades, researchers have applied an array of advanced scientific techniques to the shroud.

X-rays, ultraviolet and infrared imaging, laser scanning, and chemical analyses have all been employed to uncover its secrets.

Yet the most profound insights came with the advent of genetic and forensic technologies in the 21st century.

In 2015, a team of biologists and geneticists led by Professor Giani Barkachi of the University of Padua gained unprecedented access to the shroud.

Their goal was to investigate the ancient biological traces embedded in the linen.

Using sterile micro-vacuum devices fitted with ultrafine filters, the researchers carefully collected dust, pollen, skin fragments, and other microscopic particles.

These samples were taken not only from the surface but also from deep within the fibers, where centuries of handling and exposure could preserve material from every person who came into contact with the cloth.

Special precautions were taken to prevent modern contamination, as even a single speck of dust or skin cell could distort the results.

The samples were transported to ultra-clean laboratories and analyzed using next-generation sequencing (NGS).

The team focused on mitochondrial DNA, which is more stable than nuclear DNA and allows researchers to trace maternal lineages across generations.

When the sequencing results were complete, the data astonished even the most experienced scientists.

The shroud contained DNA from an extraordinary diversity of human populations.

Traces were detected from Europe, the Middle East, North and East Africa, South Asia, and even East Asia.

This genetic mosaic confirmed that the shroud had a long and complex history of travel.

DNA from the Middle East aligned with historically isolated communities in Israel, Jordan, and Lebanon, suggesting a connection to the region where Jesus lived.

European DNA corresponded with centuries of documented European custody, including religious custodians and pilgrims.

African and Asian DNA implied contact with communities far beyond the Mediterranean world, revealing a history that could not be explained by a 14th-century European forgery.

Alongside DNA, palynology—the study of pollen—offered additional insights.

Independent researchers, including Professor Aanome Dan of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Swiss forensic expert Max Frey, identified pollen grains from 58 plant species on the shroud.

Seventeen of these species were native to Europe, consistent with the shroud’s known history.

The remaining pollen came from the Middle East, Anatolia, and the Judean desert.

Among the most striking finds was Gundelia tournefortii, a thorny desert shrub whose pollen was concentrated around the head and shoulders of the image.

This plant is believed to have been used to create the crown of thorns described in Gospel accounts, and its presence supports the shroud’s connection to Jerusalem in the first century.

Another botanical marker, Zygophyllum demosum, endemic to the Judean desert and Sinai Peninsula, was also present in significant quantities.

These findings indicate that the shroud spent considerable time in the Holy Land.

The pollen is an invisible geographic fingerprint, impossible to forge artificially, offering strong evidence of the cloth’s ancient eastern origin.

Blood analysis further confirmed the extreme trauma endured by the man depicted on the shroud.

Using transmission electron microscopy and Raman spectroscopy, Italian researchers led by Professor Julio Fanti examined the stains at the nanoscale.

They discovered human blood of type AB, one of the rarest blood groups.

The blood contained unusually high concentrations of creatinine and ferritin, biochemical markers consistent with severe trauma, dehydration, and muscle damage.

This suggests the individual underwent intense physical suffering, consistent with Roman scourging and crucifixion practices described in historical accounts.

The red color of the blood stains, preserved over two millennia, was another remarkable detail.

High levels of bilirubin, a compound released during extreme physiological stress, maintained the vibrant red appearance.

This is not mysticism but biochemistry, reflecting the intense suffering recorded on the cloth.

No paint, pigment, or artistic technique could replicate these molecular signatures.

The Shroud of Turin has also been the subject of radiocarbon dating.

In 1988, three laboratories—Oxford, Zurich, and Arizona—tested a small edge sample and dated it to the Middle Ages, between 1260 and 1390.

At the time, this seemed to confirm skepticism about the shroud’s authenticity.

However, later investigations revealed that the sample had been taken from a repaired section of the cloth, reinforced with medieval cotton and contaminated over centuries by handling.

Chemical analysis showed the presence of cotton fibers and alizarin dye, meaning the test measured a later repair rather than the original linen.

Consequently, the 1988 dating does not reflect the true age of the shroud.

Modern analysis using wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS), pioneered by Italian physicist Liberato Daro, examines the molecular degradation of cellulose fibers.

Unlike radiocarbon dating, WAXS measures intrinsic changes in linen over time.

When applied to the shroud, the results indicated linen consistent with first-century textiles, aligning with fabrics recovered from ancient sites in Israel, such as Msada, dating to approximately 50–74 AD.

This method offers a more reliable estimate of the shroud’s age, confirming its origin in the biblical era.

The image itself remains a profound mystery.

It is not pigment or ink, but a chemical imprint only 200 nanometers deep, formed by oxidation and dehydration of the linen fibers.

Attempts to reproduce it using heat, lasers, or chemical treatments suggest that an intense, short burst of vacuum ultraviolet energy would be required.

The shroud also encodes three-dimensional information; the intensity of the imprint corresponds to the distance between the body and cloth.

NASA studies have verified this 3D encoding, which is impossible to achieve manually.

Even minute details, such as the impressions of coins over the eyes minted under Pontius Pilate, match historical evidence from 29 AD.

Together, the evidence from DNA, pollen, blood chemistry, and molecular imaging points to the shroud’s first-century origins in Jerusalem.

It is not a painting, a forgery, or a medieval creation.

Rather, it is a preserved forensic record of a real human being, whose suffering, burial, and movement across continents over two millennia have left a trace visible to modern science.

Today, the shroud remains carefully stored in Turin, accessible only to select researchers under strict conditions.

Its silence belies the wealth of information embedded within.

Scientists continue to explore its mysteries, seeking to understand the source of the energy that formed the image and the complete history of its travels.

While faith and legend have long shaped public perception, the integration of biology, chemistry, physics, palynology, and historical research now provides a tangible record of an artifact that has touched human history in extraordinary ways.

For believers, the shroud is a sacred witness to the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

For skeptics, it remains a challenge to reconcile science with the artifact’s complex evidence.

For historians and scientists, it is both a puzzle and a repository, containing layers of genetic, botanical, and biochemical information that document the human journey across time and geography.

It is, in every sense, a living record of humanity.

The Shroud of Turin, long a subject of faith, art, and speculation, now stands as a testament to what modern science can uncover.

It is a relic that transcends belief, offering measurable data on travel, suffering, and human interaction spanning two thousand years.

As research progresses, it may one day reveal the final secrets of its origin, its image, and its journey—a silent yet eloquent witness to events that shaped human history.

In a world where miracles are often questioned and history constantly reinterpreted, the shroud continues to challenge assumptions.

It demonstrates that science and faith can coexist in the pursuit of understanding, revealing truths that are simultaneously spiritual, historical, and empirical.

The Shroud of Turin, in all its complexity, remains perhaps the most remarkable artifact ever examined—a document of suffering, survival, and the extraordinary path of an object that has witnessed humanity across millennia.

News

NEW Megastructure Found Underneath Giza Pyramids Archaeologists and researchers are stunned after reports of a MASSIVE NEW MEGASTRUCTURE discovered beneath the GIZA PYRAMIDS. Using advanced scanning technology, including muon tomography and ground-penetrating radar, scientists detected a previously unknown void or chamber that could rival the size of some pyramid internal passages.

The discovery raises urgent questions: Was this part of an ancient construction plan, a hidden burial chamber, or evidence of lost technologies from Egypt’s past? Experts warn that the find could rewrite our understanding of pyramid construction and the ingenuity of the ancient civilization that built them.

Click the article link in the comments to explore what may be one of the most shocking archaeological discoveries in decades.

Leaked Pyramid Imaging Sparks Global Debate Over Ancient Technology A wave of intense debate has swept through the global archaeology…

Experts Just Released Raw Images Of What They Found Beneath The Pyramids — Scientists Are Alarmed

Uncovering Egypt’s Hidden Past: The Mysteries Beneath the Pyramids For thousands of years, Egypt’s pyramids have stood as silent sentinels…

The Odd Vanishing of Amelia Earhart Amelia Earhart’s disappearance remains one of the most puzzling mysteries of the 20th century. In 1937, during an ambitious attempt to fly around the world, the pioneering aviator vanished over the Pacific Ocean along with navigator Fred Noonan.

Despite extensive search efforts at the time, no confirmed wreckage was ever found.

Over the decades, theories have ranged from navigational error and fuel exhaustion to capture or survival on a remote island.

Each new lead has promised answers, yet none has fully explained how one of the most famous figures in aviation history could simply disappear—leaving behind a mystery that continues to intrigue the world.

Amelia Earhart: The Enduring Mystery Behind the Disappearance of Aviation’s Greatest Pioneer More than eight decades after her disappearance, the…

Proof at Last? New Search for Amelia Earhart!

The Ongoing Mystery of Amelia Earhart: New Searches and Theories Amelia Earhart, the pioneering aviator who vanished without a trace…

DNA of Cleopatra Has Finally Been Analyzed — And What It Revealed Is Terrifying

Cleopatra VII: Power, Bloodlines, and the Genetic Truth Behind Egypt’s Last Queen Cleopatra VII Philopator remains one of the most…

Cleopatra’s DNA Tells a Terrifying Story — The Queen May Not Be Who History Promised A stunning scientific claim is shaking the foundations of ancient history as NEW DNA ANALYSIS LINKED TO CLEOPATRA’S LINEAGE challenges everything generations were taught about Egypt’s most famous queen. Long portrayed through art, legend, and political myth, Cleopatra’s true origins may be far more COMPLEX, CONTROVERSIAL, AND UNSETTLING than history books ever suggested.

What if her identity was deliberately reshaped to serve power, empire, and propaganda? As researchers debate fragmentary genetic clues and historians clash over interpretation, one question refuses to fade: WAS THE REAL CLEOPATRA ERASED AND REPLACED BY A MYTH? Click the article link in the comments to uncover the full story.

Cleopatra: DNA, Deformity, and the Dark Biology of Egypt’s Last Pharaoh For more than two thousand years, Cleopatra VII has…

End of content

No more pages to load