For more than a century, the Shroud of Turin has occupied a strange space between faith and science, reverence and skepticism.

It is one of the most examined objects in human history, yet it continues to resist definitive explanation.

Every generation seems to believe it stands on the edge of resolution, and every generation is proven wrong.

Now, a new chapter has opened—one driven not by belief or disbelief, but by artificial intelligence.

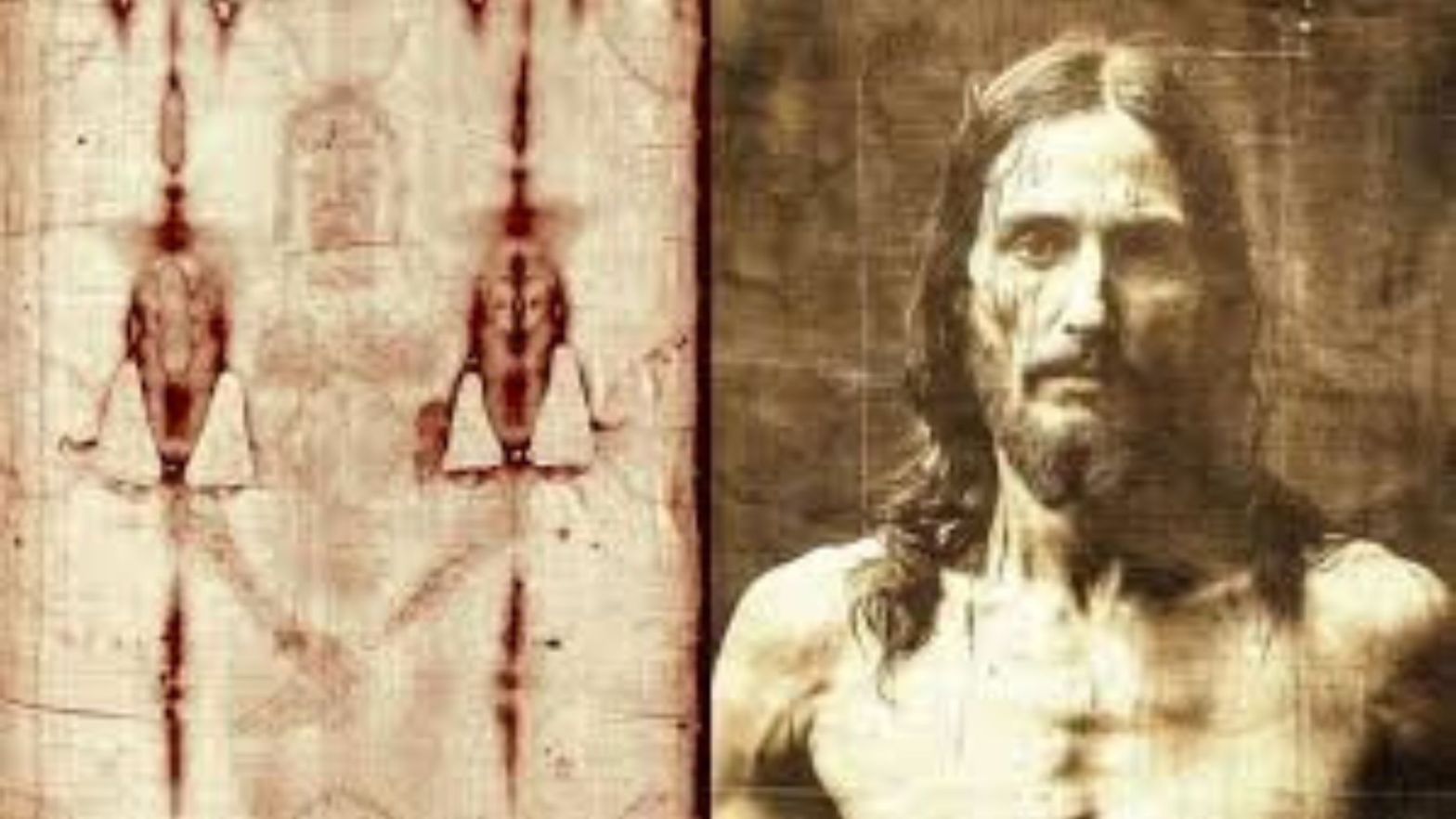

The Shroud of Turin is a linen cloth measuring roughly fourteen feet long and just over three feet wide, woven in a distinctive herringbone pattern.

Imprinted on its surface is the faint, front-and-back image of a man bearing wounds consistent with Roman crucifixion.

The marks appear at the wrists and feet, a puncture wound at the side, abrasions around the scalp suggestive of a crown of thorns, and scourge marks across the body.

The image is subtle, almost ghostlike, and yet unmistakably human.

It does not sit on the cloth as paint would.

Instead, it seems to hover within the fibers themselves.

The shroud first entered historical records in the mid-13th century in France, where it immediately attracted both devotion and suspicion.

Pilgrims flocked to see it, while critics accused church authorities of promoting an elaborate forgery.

Over the centuries, the cloth passed through noble hands before finding a permanent home in Turin in 1578.

It survived fire, smoke damage, and hurried rescue, eventually coming to rest in a climate-controlled case inside the Cathedral of St.

John the Baptist.

There it remains today, protected by layers of glass and steel, accessible to the public only during rare exhibitions.

The modern mystery of the shroud began not with theology, but with photography.

In 1898, amateur photographer Secondo Pia captured the cloth on photographic plates.

When he developed the negatives, he was stunned.

The negative image revealed a sharply defined human face and body, as though the cloth itself were a photographic negative centuries before photography existed.

Facial contours, musculature, and anatomical proportions appeared with startling clarity.

While this discovery did not prove authenticity, it transformed the shroud from a devotional object into a scientific problem.

Throughout the 20th century, researchers approached the shroud with increasing rigor.

Chemists analyzed fibers.

Forensic specialists examined bloodstain patterns.

Textile experts studied weaving techniques.

Pollen analysts identified plant traces consistent with the Mediterranean region.

None of these investigations delivered a final answer.

Instead, they deepened the mystery.

The image showed no brush strokes, no pigment binder, no evidence of paint penetrating the threads.

The discoloration appeared limited to the outermost layers of the linen fibers, affecting only microscopic fibrils on the surface.

Even more puzzling, digital analysis revealed that image intensity correlates with distance.

Areas of the cloth that would have been closer to a body—such as the nose or brow—appear darker, while recessed areas appear lighter.

When translated into three-dimensional models, the image produces a coherent relief rather than distortion.

Attempts to replicate this effect using known artistic, chemical, or physical processes have consistently failed.

Then came the most controversial moment in the shroud’s modern history.

In 1988, samples were taken from a single corner of the cloth and sent to three independent laboratories for radiocarbon dating.

All three returned dates placing the shroud in the medieval period, between 1260 and 1390.

For many, the case was closed.

The shroud, they concluded, was a medieval creation.

Yet the conclusion was not universally accepted.

Critics noted that the sampled corner had likely undergone repairs after a documented fire in the 16th century.

Textile chemist Raymond Rogers later argued that the fibers from the tested area showed chemical differences from the rest of the cloth, including traces of cotton and possible dye residues.

If the sample contained later material, the radiocarbon result could be skewed.

Defenders of the test insisted the protocols were sound.

Opponents countered that a single sample could not represent a complex, centuries-old artifact.

The debate did not end—it hardened.

What followed was a stalemate.

The shroud could neither be conclusively authenticated nor definitively dismissed.

It remained an object that refused to conform to expectations.

Into this stalemate stepped an unexpected participant: artificial intelligence.

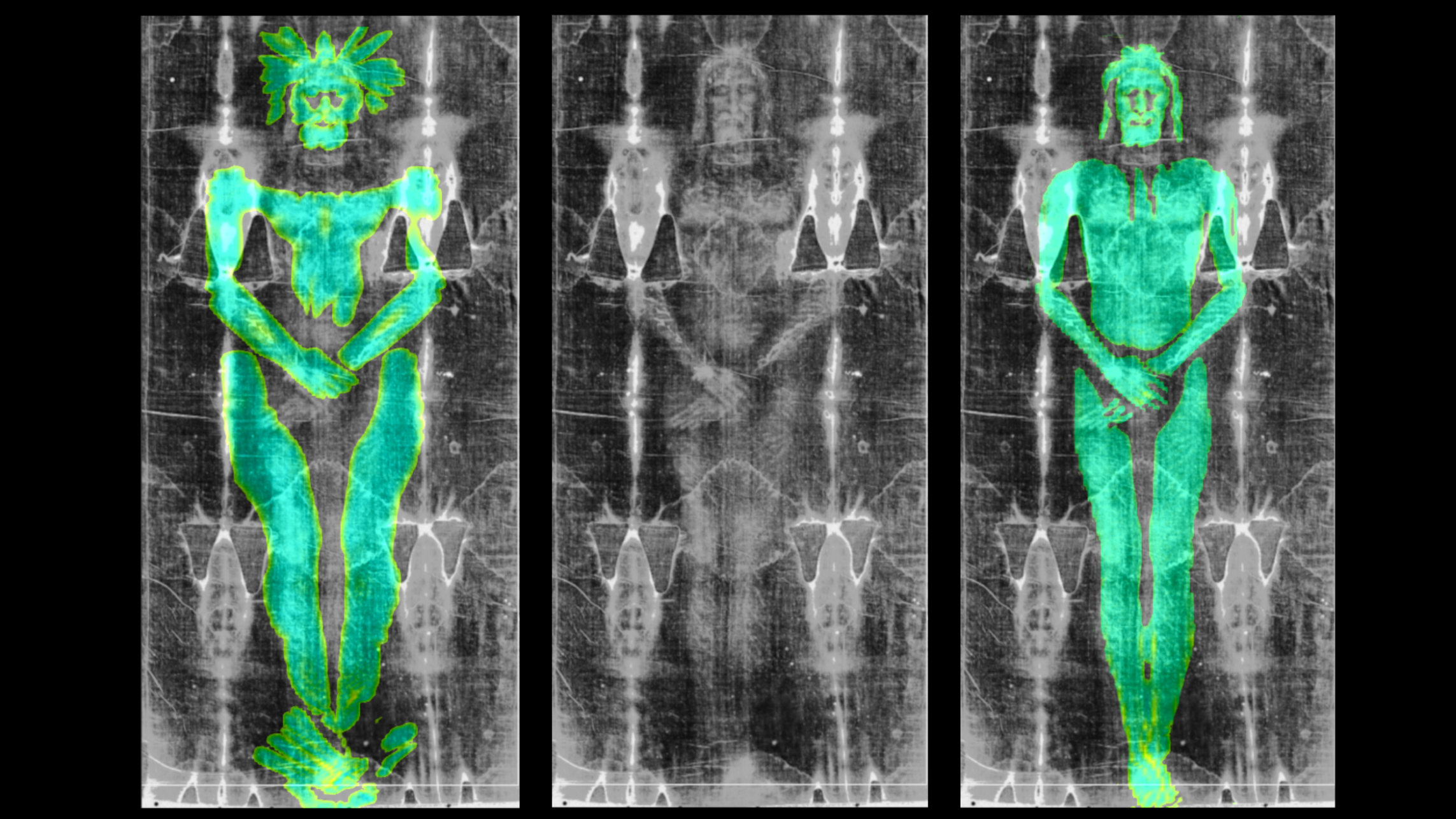

Rather than attempting to date the cloth or interpret its religious meaning, researchers turned AI toward a different question—structure.

High-resolution images of the shroud, including visible light, ultraviolet, and infrared data, were fed into advanced analytical models designed to detect patterns beyond human perception.

These systems were not programmed to “see” a face or confirm a hypothesis.

They were tasked with identifying statistical relationships within the image data itself.

The results surprised even experienced investigators.

The AI identified consistent mathematical relationships between image intensity and spatial form across multiple regions of the cloth.

These relationships persisted across different imaging methods and lighting conditions.

They did not resemble patterns produced by painting, rubbing, stamping, or contact transfer.

Nor did they align with known distortions caused by fabric draping over a body.

Most strikingly, the analysis suggested that the image behaves less like an artifact and more like a physical phenomenon.

The discoloration appears uniform at a microscopic depth measured in microns, affecting only the outer surfaces of individual fibers.

The gradient of shading follows a rule-like consistency, as though governed by an underlying process rather than artistic intent.

Bloodstains, which appear to be real human blood, sit on the cloth independently of the image, suggesting they were deposited before or separately from the image formation.

Researchers were careful not to leap to conclusions.

Artificial intelligence does not provide explanations; it reveals patterns.

It cannot identify the mechanism that produced the image.

It can only demonstrate that the image contains order—order that has not been satisfactorily explained by existing theories.

In controlled comparisons, linens treated with heat, chemicals, or pigments failed to reproduce the same statistical structure.

This does not mean the shroud has been “proven” authentic, nor does it confirm any religious claim.

What it means is that the object still resists classification.

If it is a medieval creation, it represents a level of technical sophistication unmatched by any known method from that era.

If it is older, its formation process remains unknown.

In either case, the shroud challenges the boundaries of current understanding.

The response from the scientific community has been cautious but intrigued.

Some describe the image as a form of “spatial encoding,” others as a “degradation signal.

” These terms acknowledge complexity without asserting cause.

Skeptics warn against overinterpretation and emphasize the risk of pattern recognition bias.

To address this, teams have repeated analyses using different datasets and blind methods.

The anomalous structures persist.

Meanwhile, religious authorities have largely remained silent.

After centuries of controversy, restraint is understandable.

Any statement risks being claimed as validation or dismissal.

For now, the data speaks for itself.

What artificial intelligence has done is not to solve the mystery of the Shroud of Turin, but to reframe it.

The debate is no longer solely about age or belief.

It is about process.

How does an image form on linen without pigment, pressure, or penetration? How does it encode spatial information without distortion? Why does it obey rules that resemble mathematics more than art?

The shroud remains what it has always been: a challenge.

It challenges believers to examine faith without fear of inquiry.

It challenges skeptics to confront evidence without dismissiveness.

And now, it challenges science to explain an image that behaves like no other known artifact.

History has not changed—yet.

But the questions have sharpened.

And for an object that has survived centuries of fire, debate, and doubt, that alone may be its most enduring power.

News

Archaeologists Might Have Finally Discovered What Ancient Egyptians Used to Make the Scoop Marks

Uncovering the Mystery of the Aswan Quarry Scoop Marks For decades, archaeologists have puzzled over the peculiar hollows etched into…

What Really Happened Inside Rob Reiner’s Home — The Hidden Truth No One Talked About

Rob Reiner: The Tragedy Behind the Legend In a quiet Brentwood mansion, where sunlight once reflected off pristine white walls…

At 59, Rick Harrison Confirms His Son’s Life Is Over!

The Rise, Triumphs, and Trials of the Pawn Stars Family For decades, the Harrison family captivated audiences with their charismatic…

Cesar Milan From Dog Whisperer Sentenced To Life Imprisonment

Caesar Milan: Triumphs, Trials, and the Journey Behind the Dog Whisperer Caesar Milan, widely known as the Dog Whisperer, is…

PAWN STARS Corey Harrison Heartbreaking Tragedy Of From “Pawn Stars | What Happened to Corey

Corey Harrison: Triumphs and Trials Behind the Pawn Stars Legacy Corey Harrison, best known as “Big Hoss” from the reality…

Pope Leo XIV SHOCKS THE WORLD 15 MAJOR CHANGES TO CATHOLIC CHURCH TRADITIONS! Cardinal burke…

Pope Leo XIV and the Day the Catholic Church Changed At 6:47 a.m.Rome time, without announcement or ceremony, a 47-page…

End of content

No more pages to load