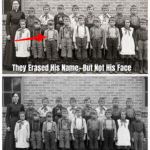

The Boy Who Was Forgotten: Unearthing a Century-Old Mystery at Oakidge Elementary

In the autumn of 1917, while the world was engulfed in the turmoil of war, the small rural community surrounding Oakidge Elementary in Pennsylvania sought a fragile sense of order.

Children in stiff woolen clothing and starched pinafores gathered for the annual school photograph, posed against the familiar brick wall that had seen decades of similar ceremonies.

Cameras of the era demanded stillness; for thirty seconds, the children were to suspend all motion, every small gesture of childhood forbidden under the weight of glass plates and mechanical shutters.

Miss Harriet Caldwell, the schoolteacher, stood at the edge of the frame, her hand resting on the smallest student, her expression as rigid and commanding as the discipline she enforced in the classroom.

At first glance, this photograph was indistinguishable from countless others taken in schools across America that year—a quiet, carefully ordered record of a single class frozen in time.

Yet, nearly a century later, the image would reveal an anomaly that no archivist could ignore.

In the winter of 2019, Clare Dennison, a volunteer archivist at the County Historical Society, discovered the photograph while cataloging the society’s vast collections.

Initially, she almost dismissed it: another array of solemn children, another artifact of a vanished world.

But something compelled her to look closer, something in the composition of the children that unsettled her.

She photographed the image and posted it to a historical photography forum, asking whether anyone else noticed anything unusual.

The response was immediate and widespread.

Viewers across the country fixated on a single boy in the second row, three positions from the right.

His expression seemed oddly knowing, too mature for his age; his features appeared unnervingly distinct, almost illuminated in a way the other children were not.

Some described a sense of being watched, a feeling that his gaze followed them, regardless of where they stood.

Skeptics attributed the unease to psychological pattern recognition, while others whispered of ghosts.

Clare, however, sensed something else entirely.

She felt a historical puzzle waiting to be solved.

Clare resolved to identify every child in the photograph, to restore the names of those frozen in time, believing that naming them might resolve the anomaly.

She began with Oakidge Elementary’s enrollment records from 1917, cross-referencing them with census data, birth certificates, and genealogical records held by local historical societies.

One by one, the children revealed themselves: Margaret Fulton, the banker’s daughter with the white bow; Thomas Weaver, son of the local miller; Sarah Pritchard, Emma Chen, Jacob Holloway, Ruth Morrison.

Letters and emails to descendants confirmed many identities, and with each response, the photograph became less a mystery and more a human document.

All but one child.

The boy who had provoked unease remained unidentifiable.

Clare checked and rechecked her records.

The class was fully accounted for in the enrollment ledger, yet the boy’s name was absent.

Twenty-three children were listed, twenty-three children stood in the photograph—but only twenty-two names matched.

It was impossible, yet undeniable.

Something had been deliberately erased.

Driven by frustration and curiosity, Clare expanded her investigation.

She combed school board minutes, teacher contracts, disciplinary reports, and local newspapers.

She visited nursing homes and senior centers, showing the photograph and asking residents if they recognized anyone.

Eleven elderly individuals with family ties to Oakidge Elementary were able to confirm some names, but nearly all exhibited gaps in memory when confronted with the boy.

Several shifted uncomfortably or changed the subject entirely.

One man, the grandson of Thomas Weaver, offered a chilling remark: children sometimes disappeared, he said, quietly, routinely, without explanation.

When pressed, he refused to elaborate.

As Clare dug deeper into the historical context of 1917, the unsettling pattern began to make sense.

The United States had entered the First World War six months earlier, and communities were gripped by paranoia and rigid expectations of loyalty.

Schools had become instruments of Americanization, places where children were monitored for any hint of disloyalty or foreign influence.

In Pennsylvania’s rural communities, where generations of German immigrants lived, families Anglicized their names, stopped speaking their native language in public, and destroyed personal artifacts that might mark them as outsiders.

Teachers were tasked with enforcing conformity, sometimes harshly, and children who failed to meet behavioral or patriotic standards risked removal or exclusion.

Progressive-era social reforms added another layer of surveillance.

Institutions for orphaned, disabled, or “troublesome” children expanded rapidly.

Teachers were expected to identify those who deviated from accepted norms and to ensure that they were separated from their peers.

Poverty, ethnicity, disability, or a personality that did not conform could mark a child for institutionalization.

Such children might vanish from school records, never to be seen again, their absence normalized by a community willing to turn a blind eye.

In this environment, Clare realized, it was plausible for a child to be removed from memory while still captured in a photograph, a silent witness to an unspoken tragedy.

Yet the photograph itself suggested something more deliberate.

Clare commissioned a high-resolution scan of the image, examining each pixel for evidence.

The boy’s shadow fell at an angle inconsistent with the sun’s light on the other children.

His shoes, lighter and less defined than the sturdy footwear of his classmates, suggested a different presence entirely.

His hands, perfectly still, contrasted with the faint blur of involuntary motion visible in the others.

His face, sharp and crystalline, seemed impossibly clear for a 1917 exposure, as though he had been added to the image afterward.

Experts in historical photography confirmed her suspicions: the boy had been inserted via composite printing—a costly, meticulous technique rarely used for school photos.

The implications were chilling.

Why go to such lengths? Clare pursued the answer through coroner records, court documents, and archival inquiries.

Months later, she discovered a coroner’s report from November 1917: a male child, approximately eight years old, had died on the grounds of Oakidge Elementary from a fall out of a second-story window.

His name was unknown, and the body had been claimed by the county.

The teacher, Miss Caldwell, had filed a brief statement, describing the accident as the result of the child’s disobedience.

There were no newspaper reports, no obituary, nothing to mark the boy’s existence in the public record.

This discovery explained much.

The boy had been living at or near the school, but he had not been an enrolled student.

His death, inconvenient and shameful, was quietly handled.

The photograph, Clare concluded, had been altered after the fact to include him, to make him appear a part of the class, to cover a gap in official record.

It may have been a gesture of care, an attempt to preserve his dignity in the only way possible—or a practical attempt to protect the teacher and the school from scrutiny.

In either case, it ensured that, though erased from official memory, the boy remained visible.

Clare traced additional documents confirming that the school had undergone scrutiny following anonymous complaints about safety.

While the investigation made no reference to the child, the timing suggested that the altered photograph may have been used to demonstrate the school’s normalcy and accountability.

Miss Caldwell’s household records suggested she may have been caring for the boy informally, further complicating the circumstances of his death.

The entire community, Clare realized, had participated in the erasure, whether from fear, guilt, or social conformity.

Silence became the mechanism of survival, and complicity was inherited across generations.

Despite exhaustive research, the boy’s true identity remained a mystery.

Yet Clare achieved something equally important: she recovered his story.

She transformed the boy from a nameless anomaly into a historical subject whose existence and fate could be acknowledged.

The County Historical Society, after reviewing her findings, created a new display that included the photograph, contextual information, and a commemorative marker on the site of the former school.

Though the boy had no name to inscribe, the dedication recognized him as the child who had been forgotten and whose image had survived the century.

On a bright May afternoon, Clare attended the dedication ceremony.

She reflected on the photograph, the meticulous work required to uncover the boy’s story, and the power of memory itself.

The community had succeeded in erasing his name, but not his presence.

In the photograph, he remained, an artificial addition that nevertheless testified to real events, real loss, and real human oversight.

Viewers continued to feel unease at the image, sensing that something was not quite right—and now they understood why.

The boy in the second row, three positions from the right, remains unnamed.

Yet he has been restored to history in a way that is perhaps more meaningful than a simple record of his birth or death.

He reminds us of the consequences of silence, the weight of social conformity, and the importance of acknowledging the hidden tragedies of the past.

The photograph endures as a testament to both the fragility of memory and the persistence of truth, proving that even when a community attempts to erase a life, traces of that existence can survive, waiting for someone to look closely enough to notice.

In the end, the boy stands not only as a figure in a photograph but as a symbol of the resilience of history itself.

He was never meant to be forgotten, and for over a century, he was—except for the image that preserved his presence, the unease that drew attention to him, and the relentless pursuit of one woman who refused to let him remain unknown.

Though his name is lost, his story has been recovered, and he will continue to stand in that second row for as long as people are willing to see him, to acknowledge him, and to remember.

Some children, it seems, were never meant to disappear.

News

The Gate That Was SEALED Until Jesus’s RETURN Has Just Opened

Whispers in Stone: The Golden Gate and the Eastern Wall of Jerusalem In the heart of Jerusalem, the eastern wall…

AI FOUND an Impossible Signal in the Shroud of Turin, Scientists Went Silent

The Shroud of Turin: Science, Mystery, and the Limits of Human Understanding The Shroud of Turin has captivated minds for…

FBI Raids Talent Agent’s Beverly Hills Mansion — 28 Missing Models Found

On a quiet morning in Beverly Hills, the tranquility of an affluent neighborhood was shattered by sirens and flashing lights….

Secrets of ‘The Last Supper’ – What Did Da Vinci Really Hide in His Masterpiece

Five centuries have passed since a genius left an enigmatic masterpiece on a wall in Milan, yet its secrets continue…

The Heartwarming Reunion: Jennifer Aniston and Her Beloved Dog Norman’s Touching Moment on Set

Introduction In a world where celebrities often seem larger than life, it’s the small, intimate moments that remind us of…

The Heartbreaking Truth Behind Jennifer Aniston’s Life at 56

Introduction At 56, Jennifer Aniston stands as a beacon of talent and beauty in Hollywood. For decades, she has captivated…

End of content

No more pages to load