At 6:00 local time, a loud Ukrainian drone swarm pushed into Russia’s Rosttoff region, and it was not chasing a quick hit.

The engines announced the attack on purpose because the real objective was to force Russia’s air defenses to react on instinct, fast and hard.

Zu23 crews and Pancer S1 batteries opened fire in sequence and early reports claimed multiple kills within minutes as the sky filled with tracers and short sharp bursts.

But every successful intercept carried a hidden cost because hot barrels, shrinking ammo, and tunnel vision can turn confidence into a trap.

While operators and gunners stared upward at targets that were easy to see, something else was moving where optics struggle and radars start to lose clean angles.

Verba man pads teams scanned for leakers.

Yet debris, heat clutter, and false contacts made the picture messier by the second.

Then wide area jamming came online and some drones dropped out which only deepened the feeling that the threat was finished.

That is the moment this story becomes dangerous because modern drone warfare does not end when the board turns green.

Stay with military force like the video and subscribe because the next part shows how layer defense can win every layer and still lose the mission.

The first move was not about precision.

It was about forcing a reaction and Ukraine used noise as a weapon.

Several dozen drones came in low and loud so everyone could hear them.

And that sound pushed Russian crews to respond fast instead of thinking slow.

When a defender believes the main threat is obvious, the defender points every eye and every gun at the obvious target.

And that is the trap a swarm can set.

From the ground, it looked like a simple air raid.

But in the air, it was more like a timed drill meant to burn attention.

That framing matters because once attention is fixed, everything else becomes easier to hide.

Russia’s Zu23 gun trucks are built for the kind of fight where a human can see the target, judge the angle, and fire without waiting for radar to solve it.

In the account, one gunner picked up the lead drone at around 1,400 m through a reflex site, squeezed both triggers, and watched the first burst walk off to the left.

He corrected by a small practical rule.

Shifting the aim a couple of meals to the right, then fired again and connected.

A 23 mm hit is not just a hole in a frame because a light airframe carrying gasoline turns into burning fragments in an instant.

So, one drone became a signal to the whole line because it proved the threat was real and it proved the guns were working.

That confidence is the hook because confidence makes crews stay on the same task longer than they should.

Along the gun belt, multiple trucks engaged at the same time, and each crew owned a slice of sky like it was a lane on a highway.

The method stayed basic fire, observe, correct, fire, and it works because it keeps the loop short and under human control.

No radar lock was needed.

No computer lead was required.

And no complex network had to stay stable under stress.

That simplicity is a strength in the moment.

But it also creates a predictable rhythm because the crews must keep looking up and keep firing to confirm the kills.

The swarm exploited that rhythm by continuing to feed targets into view even when the losses were expected.

And while the gunners were winning the visible fight, they were also spending the one resource they cannot reload instantly, sustained focus.

The more rounds they fired, the hotter the barrels ran and the closer they moved toward the point where heat and wear started to limit accuracy.

At the same time, ammunition stacks dropped fast because the high rate of fire is the whole advantage of this system.

Within minutes, the crews were reporting intercepts, but they were also asking for a pause to reload and cool weapons.

That pause is not just a logistics detail because it opens small gaps in coverage, even if the wider network is still alive.

In real combat, gaps are not measured in hours.

They are measured in seconds, and seconds are enough for a different platform to slip through.

So, the swarm’s real mission was to pull shots, expose positions, and drain the tempo until the defense needed to breathe.

And once a defense needs to breathe, something else can move in the quiet space between bursts.

Russia’s air defense did exactly what it was built to do, and that is why it looked so convincing in the first minutes.

Gun trucks and short-range systems were knocking drones out of the sky.

So, the picture on the ground felt clean and controlled, like a textbook drill with real targets.

In the account, the outer gun belt reported 11 kills in about 6 minutes.

But the same report carried a warning because ammunition was running low and crews needed a pause to reload and cool.

That mix of success and strain is the core detail.

Since a defense can be winning on paper while its tempo is quietly being forced downward.

And once tempo drops, the battle stops being about skill and starts becoming about timing.

After the gun trucks handled the first wave, the story shifts to the layer that is supposed to erase whatever leaks through, the Pancer S1.

The engagement radar picked up a cluster of remaining airframes at roughly 6.

2 km, and the system treated them as a trackable set instead of scattered guesses.

This is where the difference in method matters because Pancer does not rely on a gunner walking tracers onto target.

It relies on radar tracking and a fire control computer that keeps updating the lead solution again and again.

So the turret and guns move to where the target will be, not where it was.

That process makes the kill chain look smooth.

And smooth is dangerous because smooth creates confidence fast.

The 30 mm rounds in the description add another edge since they do not need a direct hit to break a small drone.

A proximity fuse can burst near the target and fragments can shred control surfaces, puncture fuel, or snap a wing route.

So near is often enough.

In the account, seven targets were taken down in 19 seconds with 38 rounds.

And that kind of efficiency feels like proof that the system has the situation locked.

It also sends a message up the chain because fast results invite a simple conclusion.

The main threat has been solved.

And that conclusion can spread faster than the facts.

Especially when crews are tired and the sky is full of burning pieces.

This is the point where the trap tightens because the defense is now rewarded for focusing on the most visible kind of target.

Every sensor, every optic, every order is aimed at aircraft shapes against open sky.

And that narrows the definition of what a real threat looks like.

Once a defender adopts that definition, the attacker can win by changing the geometry, not by bringing more drones.

A platform that stays low, hides in terrain lines, and avoids clean angles does not have to beat Pancier in a fair fight because it is trying to avoid being treated as a target at all.

So the danger is not that the layers failed at their jobs, but that the jobs were triggered on the wrong cues.

And that is how a system can be correct and still be misled.

That is why the most important part of this story is not the drones that were shot down, but the habits those shootowns reinforced.

And with those habits in place, the air picture can look safe right before something slips through the blind space underneath it.

The real intruder did not race through the center of the air picture because it slid under it.

And the source describes it moving at roughly 15 meters above the ground.

While the loud swarm pulled eyes upward, this drone followed river beds, drainage lines, and shallow dips.

So terrain stayed behind its body from most viewing angles.

That is not magic stealth.

It is geometry because it does not need to disappear from physics.

It only needs to avoid the exact angles that crews are watching.

And once the defender’s gaze is fixed on the open sky, the groundhugging lane becomes a quiet highway.

That is where the fight shifts from who shoots better to who chooses the better route.

For ZU23 crews, the weakness is simple and it is human because an optical gun needs contrast to work fast.

A drone silhouetted against bright morning sky gives a clean shape and a gunner can walk fire onto it with small corrections.

A drone backed by trees, water glare, and broken shadows gives no clean outline, so the eye hesitates.

The sight picture swims, and the target is easier to miss.

Even if a crew looks toward a riverbed, what appears in the optic is often clutter, not a clear aircraft shape.

And clutter makes a fast decision harder.

So, the same method that is deadly against visible targets becomes less certain when the target refuses to rise into view.

That is why the intruder’s low path matters because it attacks the visual rules the gun belt depends on.

It also matters for radar guided layers and the source points to two ideas, radar horizon and filtering.

Short-range radars and fire control software are tuned for the threats they expect, which usually means targets approaching from above or crossing in open air.

A small object staying below the radar horizon will not produce a track and an object with a small return can be rejected as ground clutter, especially when the scene is messy.

In simple terms, the drone does not have to beat Pancier in a duel because it tries to avoid being scored as a target at all.

And that creates a dangerous gap because a layered system can be excellent against what it sees while still missing what it is not looking for.

As the swarm was being cut down, Russia brought out the close-in insurance layer.

Verba manpads teams spread across rooftops, tree lines, and small rises.

The Verba seeker is described as triband using multiple channels to judge what is real, and that is meant to reduce simple decoys.

But the battlefield after a swarm is not clean.

It is filled with burning fragments, hot pieces tumbling down, and brief heat flashes that appear and vanish.

In the account, at least one team fired at what they believed was a drone.

Yet, it was falling debris still radiating heat from the earlier engagements.

That mistake is not a sign of incompetence.

It is a sign of overload because clutter grows when many targets are destroyed in a small space.

At the same time, the low intruder still did not fit the lock picture because it carried a weaker heat signature, presented a smaller angular size, and kept breaking line of sight behind terrain.

A seeker wants a steady track, a clear outline, and enough signal to be confident.

And a groundhogging drone can deny all three without ever being fast.

So, a paradox forms because every successful intercept adds more debris to the air.

And that debris makes it harder to pick out the one threat that is actually moving with purpose.

And once the defender starts mistaking busy sky for controlled sky, the low lane stays open just long enough for the mission to continue.

Wide area jamming is meant to end a drone raid by cutting the link.

But in this story, it becomes the moment where the defense starts believing its own scoreboard.

In the source, the Russian EW system comes online around 6:31 local time, and it blankets the area with interference aimed at the most common weaknesses, GPS reception, and standard control bands.

That is a smart move in general because many drones depend on commercial navigation and familiar video or command frequencies.

So noise across those ranges can turn guidance into guesswork.

The effect shows up fast since two surviving airframes that had made it through the man pad stage are described as losing signal then falling back into failsafe behavior.

One drifts into a lazy spiral and hits the ground, and another keeps going until fuel runs out, which looks like a clean technical win.

It also gives commanders a simple story to report.

Because if the drones stop talking, the threat must be gone.

And that feeling can spread through the network faster than any careful check.

And once that feeling settles in, the fight shifts from active defense to routine cleanup, which is exactly where a hidden platform wants the opponent to land.

That matters because jamming does not just block signals, it shapes decisions.

The low-flying intruder does not collapse the same way because it is not built like a consumer-grade craft.

And the link is described as narrow, directional, and fast shifting.

Instead of broadcasting in all directions, the control channel is treated like a tight beam aimed at a relay point.

And that changes the math because broad noise spreads thin while a focused uplink concentrates power in the account.

The operator sees the interference immediately through performance changes, not through a dramatic loss.

Since video latency jumps from about 180 milliseconds to roughly 340, frames stutter and static creeps in.

That is still a problem because delay makes steering feel like driving on ice.

Yet the response is also technical and calm.

Since antenna alignment is adjusted and the beam is tightened toward the drone’s last known position.

After that correction, packet loss stabilizes and the feed becomes workable again with latency dropping to around 220 milliseconds which is degraded but usable for a controlled chase.

This is the key difference because the jamming energy is wide and constant while the drone’s link occupies a small shifting slice that is harder to hold down.

Even if the link became worse, the source stresses that the intruding drone is not relying on GPS for the final phase.

And that point changes how EW should be judged.

GPS denial is powerful against systems that need satellites to know where they are, but it is less decisive against a platform that can count its own motion and read the ground underneath.

The drone is described as using an onboard inertial navigation system.

So, it tracks acceleration and rotation to estimate position without any satellite update.

For finer control, optical flow sensors compare frameto-frame ground movement, which helps measure drift and closure even when external references are noisy or absent.

That combination does not make it immune to interference, but it keeps it stable enough to follow a plan.

And stability is what matters when the mission is based on geometry and timing.

Meanwhile, the wider air defense picture is becoming quieter because the loud swarm has been thinned.

The radar display shows fewer tracks and the radio traffic starts to sound satisfied.

In that calm, the most dangerous mistake is not missing a dot on a screen.

It is concluding the phase is over because a clean picture can be an artifact of filtering and assumptions.

So the jamming layer, even when it works, can still push the defender toward the wrong posture since it turns an active hunt into a checklist.

And when a checklist replaces suspicion, the stage is set for the decision that follows.

The kind of decision that puts a crude aircraft into the air to confirm what everyone wants to believe.

The MI8 launch is where this episode stops feeling like air defense success and starts looking like a trap closing because routine procedures can be predicted and exploited.

After Russian crews judge the air picture as clean, a Mi8 was sent up to confirm the scene, check wreckage, and document the result, which is a standard step after a drone incursion.

In the source, the helicopter gets clearance around 6:23 local time, and it flies slow and low toward the debris field because the mission is observation, not speed.

That choice is logical for a crew trying to verify.

Yet, it also creates a track that a remote operator can anticipate.

When a pattern becomes readable, the threat no longer needs mass.

It only needs timing.

And that is where the story tightens.

The low-flying Ukrainian drone is described as staying patient, watching from distance, and using brief gaps in the tree canopy to confirm direction.

It is not chasing a perfect video lock every second because the goal is to build intercept geometry, not to stare at the target non-stop.

Small heading changes keep the drone on a cut off line, and terrain masking keeps it out of easy sight as it closes the gap.

A helicopter doing a search flight tends to follow a predictable rhythm with gentle turns, short orbits, and steady altitude.

And that rhythm gives the operator a clock to work with.

So the drone does not need to outrun the MI8.

It just needs to arrive at the right place at the right time, and that is the pivot.

The approach angle matters more than the speed.

And the source describes the drone choosing the behind and above lane.

For a Mi8 crew focused forward on debris and ground checks, the 6:00 high position is a natural blind area because pilots look ahead and the door gun is set for side and down.

That is not laziness.

It is task focus.

And task focus is what the earlier swarm helped create by exhausting attention and pushing the defense into cleanup mode.

By around 6:47 local time, the drone is described as emerging from below the tree line and climbing on a shallow path, closing at roughly 12 meters/s.

At that range, the goal is to be close enough that the crew has no time to spot, classify, and respond, and that pressure builds in silence.

The strike is aimed at the rotor system, not the fuselage, because the rotor head is the helicopter’s single point of failure.

The source describes impact near the rotor mast housing above the main hub, followed by detonation of a directed fragmentation warhead.

Fragments rip into the pitch control assembly, cutting the links that let the swash plate control blade angle, and without pitch authority lift becomes uneven almost immediately.

One blade can flap beyond limits, contact another blade, and shatter, and the rotor becomes an unbalanced mass that tears itself apart in fractions of a second.

At low altitude, there is no buffer because auto rotation needs time and a rotor system that still has enough integrity to bite air.

So, the MI8 drops fast, spins from residual torque, and hits with no meaningful recovery window, which turns a verification flight into the final casualty.

The tactical lesson is cold because the defense can win each visible exchange and still lose the mission when it declares victory too early.

And once that declaration is made, the most predictable move is the one that follows.

And predictability is what the attacker is waiting to punish.

This strike shows Russia’s layered air defense can work well in separate pieces, yet it can still lose when the whole system is pulled toward the wrong picture.

Optical guns, radar guided pants, verbatims hunting leakers, and wide jamming all did their jobs.

But the noisy drone wave forced every layer to stare at decoys and missed the low-flying gap.

The real threat was the quiet penetrator because it stayed under the main scan priorities and waited for the inspection moment.

Even the MI8 followed procedure, and that procedure created a predictable path, which is the easiest path to block in drone warfare.

Next, Russia will likely tighten clean sky checks, expand lowaltitude scouting, and shield helicopters with escorts or post-engagement no-fly zones, while Ukraine keeps splitting fake blows from real blows to expose forced reactions.

Subscribe to Military Force for more clear battlefield breakdowns.

News

Bruce Lee Was At Diner With His Wife Linda ‘No Asians’ — 5 Minutes Later Owner Took Down Sign Cried

There are moments that define us. Moments where we choose who we are. Moments where a single conversation can tear…

Bruce Lee Was Offered 100 Kilos Gold By Saudi Prince ‘Train My Son’ — Refusal Answer Is LEGENDARY

100 kg of pure gold stacked on a table glowing under palace lights worth $8 million in 1972. Enough money…

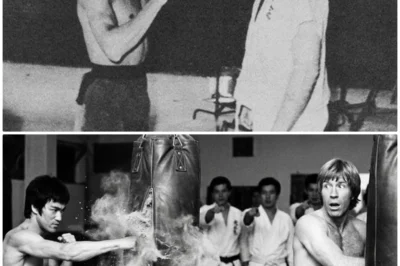

Bruce Lee Was In Ring When Sylvester Stallone Said ‘I’m Better At Boxing’ — Bruce Won Without Punch

There is a particular kind of confidence that comes from knowing your craft. From spending years mastering a skill until…

Bruce Lee Was Called Into Ring By Mike Tyson Said ‘Hit Me Let’s See’ — 4 Seconds Later Made History

Las Vegas, Nevada. Caesar’s Palace Sports Pavilion. March 8th, 1987. Saturday night, 9 p.m. The air inside the arena is…

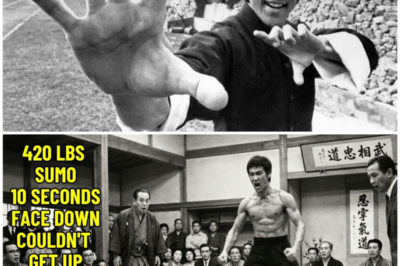

Bruce Lee Was Tokyo Professional Sumo 6’2 420 Lbs Said ‘Too Small’ — Dropped Face Down 10 Seconds

Tokyo, Japan. March 15, 1972. Bruce Lee, age 32, stepped off plane at Narita International Airport. First visit to Japan….

Bruce Lee Was Double Speed Chuck Norris 15 vs 8 Punches In 5 Seconds — Chuck Shocked 1969

5 seconds. That’s all it took. 5 seconds for Chuck Norris to realize everything he believed about speed was wrong….

End of content

No more pages to load