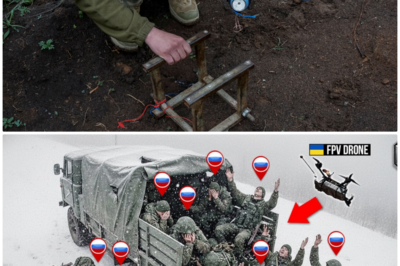

More than tens of thousands of soldiers, vehicles, and frontline positions have been lost or disabled in Ukraine in recent months, not by heavy artillery or large air raids, but by small flying devices that cost little [music] and operate with near silence.

Across today’s battlefield, forests, tall grass, and field shelters no longer offer safety.

These spaces are now exposed from above by reconnaissance drones, FPV drones, and thermal sensors that detect heat and movement with steady accuracy.

The most dangerous moments are no longer tied to direct assaults.

Risk now appears during ordinary actions.

A short pause, a slower step, a brief attempt to hide.

Any of these can be enough to trigger detection and a precise strike.

Losses are not counted only in destroyed equipment or soldiers removed from action.

The deeper damage comes from broken routines, disrupted movement, and a battlefield rhythm that cannot stabilize.

Units hesitate to move.

Positions change hands without contact.

Time itself becomes a liability.

What makes this shift more serious is how simple the tools appear.

These drones are not rare or complex systems.

They are widely available, quickly replaced, and used in repeating patterns that leave little room to adapt.

The key question is not how dramatic these strikes look, but why such basic technology is reshaping how modern [music] war is fought and what that means for every soldier on the ground.

Detection now begins long before any strike, and this first phase is where outcomes are quietly decided across forested terrain and covered ground.

Ukrainian units increasingly rely on a combination of sniper thermal scopes and aerial reconnaissance to locate Russian soldiers attempting to hide under trees, inside brush, or within tall grass.

From the ground, the forest still appears dense and protective.

From thermal optics and overhead cameras, it becomes transparent.

Thermal scopes used by snipers scan tree lines and vegetation for heat patterns that do not belong to the environment.

A human body creates a clear contrast even when the soldier remains motionless.

Breath, exposed skin, and equipment warmed by the body produce a steady signature that stands out against cooler surroundings.

Once a heat source is confirmed, drones are brought in to maintain visual contact from above.

The drone does not need the soldier to run or reveal himself openly.

A slow crawl, a shift of weight, or a small change in posture is enough to confirm identity and location.

In many cases, the target believes concealment is working because nothing happens immediately.

The process is deliberate.

Detection is not rushed.

The drone circles at a distance while ground observers verify that the heat signature remains consistent.

This step filters out animals, decoys, and false readings.

Only after repeated confirmation does the tracking phase begin.

Soldiers hiding in tall grass face the same exposure.

Seasonal vegetation that once blocked line of sight now works against them.

Grass moves unevenly when someone crawls through it.

Thermal sensors catch the heat trail left behind.

Even when a soldier stops moving, the imprint remains visible for several moments.

In wooded areas, tree trunks and fallen branches provide visual cover, but do little to block infrared detection.

Heat leaks through gaps in foliage.

Shadows that confuse the human eye have no effect on sensors.

What looks invisible from the ground appears clearly outlined on a screen.

This phase does not depend on speed or noise.

It depends on patience.

Ukrainian operators wait for confirmation rather than opportunity.

A target does not need to act carelessly or expose itself openly.

Once detected, simply staying within a monitored area is enough for tracking to continue and the engagement to move forward.

Once identification is complete, the soldier is effectively tagged.

Drones adjust position to keep the target within view while remaining high enough to avoid detection.

The person on the ground still believes he is hidden.

No weapon has fired.

No explosion has occurred.

Yet the situation has already shifted.

This is the moment when escape options narrow.

Movement increases visibility.

Staying still does not erase heat.

Attempts to dig shallow pits or cover the body with branches delay nothing.

Each adjustment adds new movement data.

In several recorded encounters, soldiers remain in place for extended periods, believing the forest provides safety.

The delay is intentional.

Operators observe patterns, check for nearby units, and confirm that the target is isolated.

Detection turns into certainty.

The operators keep watching as the soldier shifts or crawl.

Each small move tightens the sniper’s lane until the target is trapped inside one narrow pocket of cover.

When the shot finally breaks, it does not come from luck or a sudden find, as the sniper is firing into a position that has already been fixed by minutes of quiet tracking.

What looks like a random encounter is in fact the end of a longer process.

The forest no longer hides people, it frames them.

This raises a direct question for anyone watching these operations unfold.

If heat and movement can be tracked this precisely, how long can traditional hiding methods survive on a battlefield watched from above? Sniper fire in this phase is used to pin the target into a predictable reaction and the FPV drone is used to close the distance while that reaction is still unfolding.

The moment the rifle cracks, the Russian soldier stops being a hidden figure and becomes a moving problem because pain and shock force him to choose between staying low or running.

If he tries to stay still, his head lifts to scan.

And that small change [music] exposes him through gaps in leaves and broken branches.

If he runs, he must pick a path.

And a path is something the drone operator can read because trees and uneven ground funnel feet into narrow lines.

The sniper does not need a perfect kill shot to change the fight.

Once the target moves, the FPV drone comes in fast and it arrives as the second pressure that removes the last illusion of time.

The drone’s camera does not need a clear face because it tracks direction, speed, and pauses, and the soldier’s own choices keep drawing a line for it to follow.

Sometimes a second FPV [music] stays higher and steadier to keep constant eyes on the area while the strike drone drops lower [music] and threads through branches.

That overhead view helps confirm the new position after each forest [music] move, and it prevents the target from slipping into a blind pocket.

When the man dives behind a thin trunk, he believes the wood is a shield.

Yet, he must lean out to reorient, and that brief lean is enough for the drone to correct its angle.

Another solider crawls into brush.

The leaves hide his shape from the ground, but the view from above keeps his route visible as he pushes branches aside.

He circles back toward the same cover because familiarity feels safer than open space, but that loop brings him back into the sniper lane, and the rifle threat returns.

What makes this sequence decisive is that it removes the normal middle phase of close combat because no Ukrainian infantry has to rush the last meters.

The sniper and the FPV drone do the risky work from different angles [music] and each one makes the other more effective because the rifle shapes behavior and the drone punishes behavior.

The targets are not fighting a single weapon because he is caught in a timing trap.

And once the first shot lands, the next threat is already closing.

In the background, units learn that any short break can turn into a fatal moment if it happens in the wrong pocket of terrain.

That pressure is constant because the sniper creates fear of sudden pain, and the drone adds fear of being followed.

And together, they compress safe choices down to almost nothing.

From your point of view, does this feel like a compact version of designated marksman plus air support? Or does it show a new kind of battle where the first shot is only the start and the FPV is the closer? The second strike in this war is not a choice because the first hit often creates a wounded target who is still dangerous and still connected to the fight.

After the initial contact, a Russian soldier may drop to the ground and stop moving.

Yet, that stillness can be a trick rather than a sign of defeat.

The sniper does not relax after the first shot because the rifle now has a new task, which is to cut the ability to escape and to block any attempt to regroup.

A follow-up round is aimed at stopping a crawl, breaking a sprint, or forcing the target to keep his head down, and each impact reduces the number of choices left.

When the soldiers tries to inch toward a ditch or a treeine, the shooter reads that route and presses again.

In these seconds, the fight becomes a countdown, and the side watching from above tries to end it before the ground can reset.

The FPV drone enters this moment after reading the situation when the target is trapped between pain and fear.

The operator does not rush, but drive the drone slowly to the target who is forced into a narrow space.

The strike is then repeated if needed because one blast that wounds is not the same as one blast that removes the threat.

In many engagements, the second FPV is launched not because the first failed, but because the first confirmed the target and stripped away the last cover.

When the first strike hits close and throws dirt, the soldier may try a desperate roll into a shallow depression.

Yet, that move is now obvious from above and easy to predict.

The follow on drone arrives into a scene that is already measured, and it finishes the job before the target can recover breath [music] or plan.

This is the logic of full neutralization and it is shaped by the fact that a battlefield under electronic pressure punishes hesitation on both sides.

Radio links can be jammed and drones can lose control.

So operators act as if every second is borrowed time if a drone has a clean path.

Now waiting can mean losing the window and losing the window can mean a wounded enemy reaching friends or reaching a trench.

That is why the sequence stays tight because the side running the kill chain wants to end the problem inside one short span, not let it stretch into [music] a longer fight.

This is also why fiber optic FPV has become a serious detail in the story because it changes what electronic [music] warfare can block.

When control is carried through a physical line, the drone is less dependent on a radio signal and it can keep guidance even in a noisy environment.

That gives operators more confidence to commit deep into trees or broken buildings because the link is steadier and the final seconds are less fragile from the ground.

This creates a harsh reality because hiding longer does not always mean surviving longer and moving does not always create escape.

In this fourth phase, the fight shifts from hunting a single man to breaking the places and tools that allow whole groups to keep attacking.

An FPV drone does not need a clear flag or a clean silhouette because the first clue is often a human routine that leaves marks in the landscape.

A thin path that cuts through grass, a fresh track line that repeats the same turn, or a dark opening that does not match the tree line can give the sight away.

Once the camera catches that [music] detail, the operator slows down and holds distance.

A soldier steps out for a second and he looks left and right before moving back in.

And that single move tells the drone where the center really is.

The FPV stays low and approaches from an angle that keeps branches between it and the sky.

When the moment is right, it commits in a straight line and dives toward the opening.

And the strike is aimed at the point where men and gear [music] must pass.

Once the drone enters the structure and confirms Russian soldiers inside, it deliberately impacts a wall and detonates, and the blast can be [music] strong enough to collapse the roof entirely and seal off any chance of escape.

When the explosion brings the building down and movement erupts [music] beneath the debris, follow-up strikes become possible because the sudden collapse and frantic attempts to survive expose positions more clearly than concealment ever could.

In another common case, the target is not a dugout, but a small field shelter beside trees where a support team has been working for hours.

The FPV arrives just as the team relaxes its posture, and small movements like lifting a lid or shifting a box become visible from above.

The drone holds for a few seconds and waits for one person to step into the open, and then it drops fast and ends the routine in one strike.

The immediate effect is not only the damage because the surviving soldiers scatter and they stop using that spot and that breaks the rhythm of the unit that depended on it.

This is how an FPV drone starts to hit the structure behind the front line.

Sometimes the story then moves to a harder target because some locations are built to survive light attacks and keep functioning.

A strong building near a road junction, a crossing point that channels vehicles, or a fixed hub where orders and signals are managed, can keep supporting assaults even when smaller sites are being wiped out.

When a target reaches that level, the chain brings in the MiG 29, and the aircraft delivers a guided bomb that can crush a fixed point in one moment.

Reports have described MIG 29 strikes using GBU62 with a JDM kit against logistics points like bridge approaches and crossing areas.

On the ground, the sequence feels like a door being slammed [music] because a route that was used yesterday becomes too risky today and a building that felt safe becomes a warning sign.

units that relied on that node must reroute and rerouting costs time, fuel, and discipline because every detour creates more exposure.

This is where geopolitics becomes visible in a very practical way because a precisiong guided weapon extends reach beyond what FPV drones can solve on their own.

The defending side then faces a hard choice because protecting every fixed point is impossible.

Yet leaving one open can invite another guided hit.

Even when Russian units try to guard key central nodes with rocket launchers [music] and other short-range fire, the pattern often repeats because the moment those crews settle into a routine, the FPV drone finds the position and strikes.

The fourth phase ended with fixed nodes collapsing under heavier strikes, and that forces the surviving troops to rely on the oldest shield they still have, which is summer vegetation and low profile movement.

In early light, a small Russian group leaves the treeine and drops into tall grass, trying to make the green cover their bodies.

They move in short bursts, and each man pauses to listen because the worst fear is not a rifle shot, but the soft buzz that means tracking has already begun.

From above, the scene looks different because the grass does not hide the route.

It only slows it and slow movement creates a clear rhythm that can be read like a line on a map.

An FPV drone appears at low altitude and stays off to the side.

And it does not dive right away because the operator is measuring the pattern of stops and starts.

When one man raises his head to check direction, that small change is enough and the FPV accelerates and begins to close the gap.

The group reacts late because sound arrives after the drone has already shortened distance [music] and tall grass steals the quick sprint they need.

One soldier breaks left toward a thin patch of bushes.

Another tries to push forward and [music] a third freezes and presses into the ground, hoping stillness will cancel attention.

The FPV commits on the man who is most exposed and the strike happens near him before he can reach the next clump of cover.

A shock wave throws grass and dirt and the survivors do not know if the drone is gone or if another one is already lining up.

In another scene, a lone soldier leaves a ruined position and tries to cross an open field between two tree lines because he believes speed and open space can beat danger.

The FPV approaches from behind and stays below the horizon line.

So, the target does not notice until the buzzing is close and the shadow begins to move over the grass.

The soldier tries a short zigzag and then tries to cut back toward the same line he came from.

Yet, each turn costs speed and gives the drone an easier angle.

The most brutal moment comes when he thinks the crossing is almost done.

That is when the FPV closes.

A strike at that distance does not allow a reaction and the open field becomes a place where seconds matter more [music] than meters.

This creates a psychological trap that spreads beyond one contact because soldiers start to treat every pause as a threat and every movement as a signal that can be followed.

If they keep running, they burn energy and lose awareness.

And if they stop, they risk being hit during the moment they try to reset.

Some Russian soldiers decide the only option is to raise their rifles and fire at the drone.

In some cases, they manage to hit it and bring it down, but in other cases, the drone takes rounds and detonates in the air at a distance that is still too close, so the blast and fragments can wound the shooter anyway.

In other moments, the FPV slips away from the shots, keeps its line, and then dives straight into the target without giving a second chance.

Overall, this final phase shows that in a battlefield ruled by the low sky, even the simplest act of moving or resisting can turn into a deadly chain within seconds.

What these drones videos reveal is not a series of isolated strikes, but a deeper shift in how war is now being fought and controlled.

Across the battlefield, detection no longer begins with direct contact.

It starts with thermal sensors, quiet observation, and drones that watch long before they strike.

From that moment, time works against the target.

This system does not stop with individual soldiers.

Light vehicles disappear from supply routes.

Shelters lose their value.

Hidden weapons are exposed and destroyed.

Even large air delivered strikes now depend on drones to find targets and confirm results.

The battlefield is no longer decided only by a single front line.

It is shaped in the low airspace above fields, forests, roads, and [music] ruins where every movement can be tracked, timed, and exploited.

The open question now is whether effective counter measures can emerge fast enough to break this pattern or whether drone- centered warfare will spread and define future conflicts far beyond Ukraine.

That debate is only beginning.

What do you think comes next in the evolution of drone warfare? If this analysis helped clarify what is really happening on today’s battlefield, like the video, share it, and subscribe to Military Force for more clear reporting on how modern war is changing.

News

“Unmanned and Unstoppable: The Shocking Moment Ukraine’s Robot Erased a Russian Stronghold!” Imagine a scene where a solitary robot, once designed for logistics, transforms into a harbinger of doom on the front lines. In a jaw-dropping incident, Ukraine’s cutting-edge technology caught an entire Russian unit off-guard, leading to a cataclysmic strike that decimated their defenses in an instant. This isn’t just another battle; it’s a pivotal moment that showcases the rapid evolution of warfare, where machines are now rewriting the rules of engagement. What does this mean for the soldiers on both sides? Are we prepared for a future where robots dictate the terms of war? 👇

In a single strike, a ground robot packed with explosives erased an entire Russian defensive position. And not one Ukrainian…

“Drones of Death: How Ukrainian Technology Decimated a Russian Convoy in the Kill Zone!” In a shocking turn of events, Ukrainian drones have turned the tide of battle by targeting a truck full of Russian soldiers, resulting in a catastrophic strike that has left military analysts reeling. As the drone operators watched from the safety of their command posts, the unsuspecting troops became mere pawns in a deadly game of aerial warfare. The precision of these low-flying FPV drones has exposed the vulnerabilities of traditional military tactics, forcing commanders to rethink their strategies in a conflict where technology reigns supreme. What will this mean for the future of warfare? Are we witnessing the dawn of a new era where drones dictate the battlefield? 👇

Dozens of Russian targets were detected and struck from the air within just a few hours, including infantry groups, vehicles,…

“Elon Musk’s Grok AI Shatters Faith: The Unbelievable Truth About Jesus Revealed!” When one of the world’s most advanced AI systems, Elon Musk’s Grok AI, dared to tackle the age-old question of who Jesus really is, the response sent shockwaves through the religious community. Instead of offering the comforting narratives we’ve come to expect, this AI presented a cold, hard truth that challenges the very foundation of faith itself. Could this be the dawn of a new era in understanding spirituality, or just another tech gimmick? 👇

WHEN THE MACHINE LOOKED AT GOD — AND FAITH FELT THE FLOOR GIVE WAY The question was older than empires….

“The Shocking Truth Behind Elisa Lam’s Mysterious Death: Was It Murder, Madness, or a Dark Conspiracy?” In a world where the line between reality and the supernatural blurs, the tragic tale of Elisa Lam has taken a turn that no one could have predicted. As new evidence emerges, we delve into the twisted corridors of the Cecil Hotel, where secrets fester and shadows whisper. Was this vibrant young woman a victim of her own mind, or was there something far more sinister lurking in the depths? Prepare yourself for a revelation that will leave you questioning everything you thought you knew about this haunting mystery. 👇

The Elisa Lam Case: A Hollywood Tragedy In the heart of Los Angeles, the Cecil Hotel stood like a silent…

“Unmasking the Real Killer: How a Shocking New Lead Could Change Everything in the JonBenet Case!” Just when you thought the JonBenet Ramsey case was a closed chapter in America’s crime history, a bombshell discovery threatens to rewrite the narrative entirely! As investigators sift through fresh evidence, the tale takes a dark twist that could implicate those closest to the tragedy. Could the killer be hiding in plain sight? Buckle up, because this shocking revelation will have you gasping in disbelief and re-evaluating every suspect you thought you knew! 👇

THE LITTLE GIRL WHO NEVER LEFT THE HOUSE — AND THE TRUTH THAT NEVER LEFT THE ROOM America met JonBenet…

“MH370: The Hidden Signals That Could Expose a Global Cover-Up – Are We Being Lied To?” What if everything you believed about the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370 was a lie? Richard Godfrey, a retired British engineer, has emerged from the shadows with a bombshell theory that suggests the truth has been hidden in plain sight. Using nearly invisible radio signals, he claims to have pinpointed the wreckage’s location, challenging the very narrative that has gripped the world for over a decade. As the aviation industry reels from the implications, prepare for a shocking exposé that could change the course of history! 👇

The Lost Signal: A Hollywood Tragedy In the stillness of a moonless night, Richard Godfrey stood on the edge of…

End of content

No more pages to load